How the Moon was made

There is one satellite that does not need me to tell you who discovered it, because at an early age, you discovered it for yourself. The Moon has been recorded – to begin with, in carvings on animal bone – for over 20,000 years. It affects our lives in too many ways to describe, and in the next chapter we will see how it forms an active part of the Earth system.

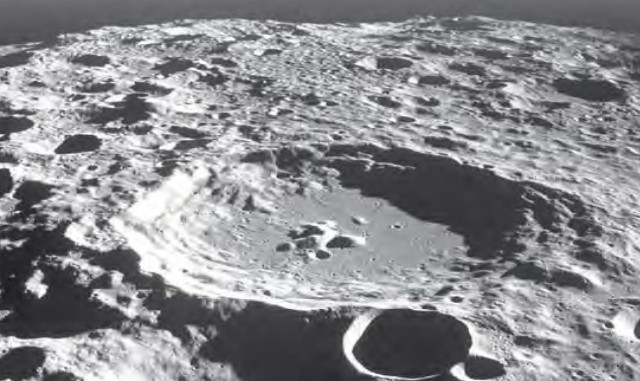

About 16 percent of the Moon's surface is covered in big, flat round areas. They are so featureless, especially to the small telescopes of early astronomers, that they are called maria, or seas, although we now know that no ship has ever sailed on them. Instead, they are solid layers of lava produced at the last stage of the solar system's formation when the Moon was bombarded by large planetesimals. Their impact produced so much heat that the immense craters they generated filled with molten rock. They are smooth today because they solidified that way and have only a thin splatter of later craters caused by meteorite impact. Many of the features around them also show signs of lava flooding.

By contrast, the rest of the Moon is made up of the highlands, and if space tourism ever gets going, this will be the destination of choice for the honeymooners.The reason is that the highlands have survived from the earliest days of the solid Moon. They are heavily cratered, and in many cases it is possible to see new craters that have obliterated parts of old ones beneath.

In the last few decades, we have found out more about the Moon for several reasons. One is that between 1969 and 1972, a dozen Americans visited the place, had a look, and brought bits back. In addition, a clutch of US, Soviet and European spacecraft have visited the Moon, and the Soviets have also returned Moon rock to the Earth. Even more startlingly, it turns out that some of the meteorites found lying about on the Earth have come from the Moon.

When scientists studied the atomic make-up of Moon rock, they were in for a surprise. Apart from some subtle differences, its composition is very like that of Earth rock. In recent years, scientists have converged on the reason why, and in the process they have found out how the Moon formed.

It is simple to form an object as big as the Moon – there are about fifteen planets and satellites in the solar system of about its size or bigger. But it is more tricky to develop a computer model of the early solar system in which the Moon can form very close to the Earth without their aggregating into one. And models which involve the Earth capturing the Moon after it formed tend to have annoyingly artificial assumptions, raising more problems than they solve. However, the data about the composition of Moon rock suggests that the Moon is in fact a visible relic of the violent formation of the solar system. There is now general agreement that the Moon was formed when a chunk of matter the size of Mars hit the Earth a glancing blow, blasting a massive piece away, which later settled down to form the civilized sphere we see today. Because the Earths surface changes so fast, the immense crater that this impact must have left is long gone. It would have topped this book's list of must-see Earth sights by some distance.