Republic of Zimbabwe

POPULATION: 15.25 million (2014)

AREA: 150,803 sq. mi. (390,580 sq. km)

LANGUAGES: English (official); Shona, Ndebele

NATIONAL CURRENCY: Zimbabwe dollar

PRINCIPAL RELIGIONS: Syncretic (part traditional, part Christian) 50%, Christian 25%, Traditional 24%, Other 1%

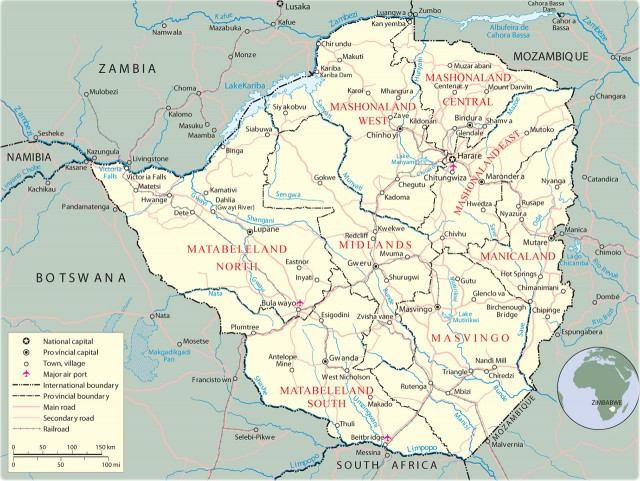

CITIES: Harare (capital), 1,752,000 (2001 est.); Bulawayo, Gweru, Mutare, Kwekwe, Kadoma, Hwange, Masvingo

ANNUAL RAINFALL: Varies from 40 in. (1,020 mm) in Eastern Highlands to 15 in. (400 mm) in Limpopo valley.

ECONOMY: GDP $14.20 billion (2014)

PRINCIPAL PRODUCTS AND EXPORTS:

- Agricultural: coffee, tobacco, corn, sugarcane, peanuts, wheat, cotton, livestock

- Manufacturing: steel mills, textiles and footwear, wood products, cement, chemicals, fertilizer, food and beverage processing

- Mining: coal, gold, copper, nickel, iron ore, tin, clay

GOVERNMENT: Independence from Britain, 1980. Paramilitary democracy with president nominated by the House of Assembly and elected by universal suffrage. Governing body: 150-seat House of Assembly, with 120 members elected by universal suffrage.

HEADS OF STATE SINCE INDEPENDENCE:

- 1980–1987 President Canaan Banana

- 1987 President Robert Mugabe

ARMED FORCES: 39,000 (2001 est.)

EDUCATION: Compulsory for ages 6–13; literacy rate 85% (2001 est.)

Although a powerful and complex kingdom some 700 years ago, Zimbabwe was one of the last countries in Africa to win its independence in the late 1900s. Impressive architectural ruins show glimpses of the nation's past grandeur. From the early civilizations that built these structures down to the modern day, Zimbabwe has played an important role in southern Africa.

GEOGRAPHY

Zimbabwe is a landlocked country in southeastern Africa, bordered by ZAMBIA to the north, MOZAMBIQUE to the east, BOTSWANA to the west, and SOUTH AFRICA to the south. An elevated ridge known as the highveldt divides the country roughly in two from southwest to northeast. An area called the middleveldt slopes down from either side of the highveldt, covering about 40 percent of the land. The extreme northwest and southeast make up the lowveldt. Mountainous terrain dominates the Eastern Highlands bordering Mozambique.

Most of the country ranges from 1,000 to 4,000 feet above sea level, and this height produces a moderate climate. However, the land is generally better suited to ranching than agriculture because of its thin sandy soils. In addition, rain falls unpredictably, leading to severe droughts that strike the land and people. Although forest covers about one-third of Zimbabwe, forested areas have been disappearing in recent years, which has caused much concern. Savanna grasslands account for much of the rest of the country. The spectacular Victoria Falls and Kariba, one of the world's largest artificial lakes, are in the northwest.

HISTORY AND GOVERNMENT

The modern country of Zimbabwe takes its name from the massive stone ruins of Great Zimbabwe that are one of Africa's most impressive archaeological sites. These dzimba dza mabwe, or “houses of stone,” were built before A.D. 1000 and testify to the rise of the earliest centralized societies in southern Africa.

Great Zimbabwe

The site called Great Zimbabwe was built by the Mashona (or SHONA) people. Its main feature is the Great Enclosure, a circular stone wall over 30 feet high and 800 feet in circumference. Inside the enclosure lie the remains of a cone-shaped tower, as well as other walls and clay building platforms. Glass beads and Chinese porcelain found at the site suggest that Great Zimbabwe was connected to SWAHILI trading networks that stretched to ports along the Indian Ocean coast.

The valleys surrounding the Great Enclosure contain other stone enclosures with similar smaller towers and clay platforms. The remains of clay floors indicate that as many as 10,000 people were living in close quarters in the area. The society featured a complex division of labor between agriculture, pastoralism, and craft activities. The labor system probably required a highly structured and powerful central authority. Additional walls at the site divided the living areas of the privileged classes from those of the common people.

The rulers of Great Zimbabwe extended their control over a wide area of the surrounding plateau from which they extracted resources and tribute. The high walls of the Great Enclosure served more as a symbol of the power of the rulers than as a real military defense. Great Zimbabwe was not, however, the only such walled settlement in the region. Some 150 smaller sites have been uncovered in Zimbabwe, eastern Botswana, South Africa, and Mozambique. One of these, Mapungubwe, in South Africa, appears to have been built earlier than Great Zimbabwe. Although not as advanced in its architecture, it too appears to have had a complex division of labor and trading ties with the coast.

The Decline of Great Zimbabwe

The state of Great Zimbabwe dominated its region until the mid-1400s. At that time the rulers began to lose control of peoples living on the edges of their empire. Around 1450 the states of Torwa and MUTAPA (also known as Mwene Mutapa and Munhumutapa) emerged. A Portuguese document dated 1506 contains the earliest existing reference to Mutapa. It, too, held power over surrounding territory and received tribute from weaker kingdoms in the area.

Portuguese traders made contact with Mutapa around 1500 and established trading posts along the ZAMBEZI RIVER and the Zimbabwe plateau. By the early 1600s, they had gained control over the gold and IVORY TRADE with the coast, and the ruler of Mutapa had to obey the orders of the Portuguese. In the 1660s a new ruler became powerful enough to force the Portuguese out of the region. However, internal divisions and rebellions in outlying areas soon fractured the state and led to its decline.

The Rise of Rhodesia

In the early 1800s the NDEBELE people moved into southwest Zimbabwe from South Africa. They were part of the ZULU nation that had been driven from its land by the eastward expansion of white settlers. Clashes with settlers resulted in the destruction of the Ndebele kingdom in the late 1800s. The displaced Ndebele made frequent raids on the neighboring Shona to obtain food, cattle, and laborers. The ethnic divisions dating from this period have remained an ongoing problem for Zimbabwe.

In 1890 armed troops of the British South Africa Company, a private firm under the leadership of Cecil RHODES, invaded what is now Zimbabwe. Despite fierce resistance from the Shona and Ndebele, Rhodes's army gained control over the region. In 1924 the area was proclaimed a self-governing British colony and named Southern Rhodesia after its leader. Like its neighbor South Africa, the colony practiced racial segregation, denying basic freedoms and civil rights to black Africans. White authorities threw black farmers off their best lands and turned the property over to a handful of influential white settlers.

In 1953 Southern Rhodesia joined with the British colonies of Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) and Nyasaland (now MALAWI) to form the CENTRAL AFRICAN FEDERATION. The main goal of the federation was to allow Southern Rhodesia access to Northern Rhodesia's abundant copper reserves and Nyasaland's pool of cheap LABOR. During this time the country's leaders took some timid steps toward granting black people a place in government. A new constitution in 1961 set aside about a quarter of the seats in Parliament for blacks.

Most black Rhodesians realized that the new arrangement was only a tactic to delay true majority rule by the indigenous population. African political groups increased their calls for democracy. In 1962 a right-wing white party called the Rhodesian Front (RF) emerged to challenge those white leaders who approved the 1961 constitution. The RF, led by the openly racist Ian Smith, dedicated itself to total white supremacy.

A year after the founding of the RF, Britain dissolved the Central African Federation and granted independence to Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland under black majority governments. This move alarmed the RF's leaders, who suspected that Britain supported black rule in Southern Rhodesia as well. In 1965 Smith, by then prime minister, declared independence for Southern Rhodesia. The British passed economic and political sanctions against Southern Rhodesia, but Smith still hoped that other countries would recognize his nation's independence.

Conflict and Negotiation

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, several black political organizations arose to challenge white rule in Rhodesia. The first group to emerge was the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU), led by Joshua Nkomo. In 1963 some members of ZAPU split off to form the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) under the leadership of Robert MUGABE and Ndabaningi Sithole. ZANU announced a policy of armed resistance, and a war of liberation against the white government began in the 1970s.

ZANU and ZAPU joined forces in 1976 to form the Patriotic Front (PF), carrying out their anti-government campaign from bases in Zambia and Mozambique. During this time the British attempted to negotiate a settlement between the rebels and the Rhodesian government. This effort resulted in the so-called “internal settlement” of 1978–1979 that put blacks into several high political offices, including president and prime minister. However, whites still controlled the real power in the country, and neither ZANU nor ZAPU accepted the deal.

In 1979 all of the parties agreed to a compromise agreement that called for free elections the following year. To reassure the white minority, 20 seats in the legislature were set aside for whites for a period of seven years. In the resulting elections, ZANU won the majority of seats, and Mugabe became prime minister of the country, renamed Zimbabwe.

Independent Zimbabwe

Mugabe moved cautiously in changing Zimbabwean society. He realized that the Smith regime had developed an impressive industrial infrastructure to offset the effect of British economic sanctions and boycotts. As a result, Zimbabwe had a relatively healthy and diverse economy that Mugabe did not want to damage. Although he pledged to resettle black people on land stolen by white settlers, he realized that moving too fast would disrupt the large-scale agriculture that provided the country's main source of export earnings.

Even so, Mugabe did make several important changes. His government turned some white lands over to black people, invested in HEALTH CARE and education, and helped more black Zimbabweans get higher positions in business and civil service. But at the same time relations between ZANU and ZAPU grew worse. In 1982 ZANU accused ZAPU of hoarding weapons for a coup and fired several ZAPU leaders from the government. The next two years saw a brutal conflict in which ZANU and its followers killed thousands of ZAPU supporters.

Throughout the 1980s Mugabe said that he wanted to turn Zimbabwe into a single-party state based on communist principles. However, the Zimbabwe Unity Movement (ZUM), a new party headed by former ZANU leader Edward Tekere, emerged just before the 1990 elections. Mugabe won nearly 80 percent of the vote, but only about half of the eligible voters participated.

The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 led Mugabe to abandon his call for a communist state but not his desire for political dominance in Zimbabwe. A new constitution adopted in 1992 made ZANU the only party eligible for state funding. Mugabe accelerated the land redistribution program in the following year. However, ordinary people found out that some of the first lands taken under the program went to high government officials.

By that time corruption and political mismanagement were ruining Zimbabwe's economy. A catastrophic drought struck in 1992, and poor government planning led to a serious food shortage. In 1996 it was revealed that government officials had stolen money from a fund for army veterans. In protest, most opposition parties boycotted the elections that year and less than one-third of the electorate voted.

In 1998 Mugabe made a fateful decision to send troops into CONGO (KINSHASA). Congo's leader Laurent Kabila, who had recently overthrown the dictator MOBUTU SESE SEKO, faced a rebellion of his own. Mugabe hoped to take control of valuable resources such as copper and diamonds that Kabila's government could not protect. His arms purchases for the war sent the country deeper into debt.

Zimbabwe struggles under a crushing foreign debt, widespread unemployment, and very high inflation. Mugabe's foreign adventures have bankrupted the treasury. Bands of armed black citizens roam the countryside forcing white farmers off their land and harassing their black workers. Although Mugabe still holds power, most observers believe that a new leader is needed before Zimbabwe can improve its situation.

ECONOMY

Zimbabwe's economy includes a fairly diverse range of activities and goods. Agriculture provides almost half of the country's export earnings: tobacco is the country's largest agricultural export, followed by cotton and beef. Zimbabwe usually produces enough to feed its people without large imports of food. But droughts in 1991–1992 and 1994–1995 destroyed much of the maize (corn) that Zimbabweans rely on for their own food.

Industry and manufacturing, well developed under the Smith regime, contribute a substantial portion of the export revenues. Leading industries include construction equipment, transportation equipment, metal products, chemicals, textiles, and food processing. However, much of the industrial infrastructure has aged and needs to be upgraded. Zimbabwe also has a mining sector that produces gold and platinum, but foreign companies dominate most mining activities.

Service industries also play a significant role in the economy, with many of them created by government programs. Violence in rural areas has damaged both TOURISM and agriculture. Many experts expect that Zimbabwe's economy will continue to decline for some time.

PEOPLES AND CULTURES

Most Zimbabweans belong to either the Shona or Ndebele ethnic groups. The Shona, made up of six main linguistic subgroups, work mainly as farmers or herders. The Shona forbid marriage between members of the same clan. Marriages usually involve a transfer of wealth from the groom to the bride's family. Married couples often live with the groom's parents. If the groom does not have wealth and gifts to offer, he may perform labor for his father-in-law.

The Ndebele (also known as Matabele) traditionally live as herders with a highly structured social system. In the 1800s they raided Shona settlements and captured Shona as servants. Their social system discouraged marriage between the two groups to ensure the dominance of the Ndebele privileged classes. Ethnic tensions between the two groups still erupt occasionally.

About half of Zimbabweans practice a mixture of CHRISTIANITY and indigenous religions based on reverence for dead ancestors. These religions include SPIRIT POSSESSION, by which religious leaders communicate with the spirit world. Although many Zimbabweans say they belong to the Catholic or Anglican church, their worship often mixes elements of indigenous beliefs. (See also Archaeology and Prehistory, Colonialism in Africa, Ethnic Groups and Identity, Harare, Independence Movements, Land Ownership, Southern Africa, History.)