South Asia: Human–Environment Interaction

A HUMAN PERSPECTIVE Hinduism is the religion of most Indians. During one Hindu religious festival, millions of Indians gather near the city of Allahabad, where the Ganges and Yamuna rivers meet. A temporary tent city goes up, complete with markets, temples, and teahouses. People visit the market stalls and pray at the temples. They also watch plays based on Hindu myths and legends.

Mainly, though, the Hindus wait for the appointed moment when they will wade into the Ganges and wash their sins away in its holy waters. To Hindus, the Ganges River is not only an important water resource, but it is also a sacred river. It is the earthly home of the Hindu goddess Ganga.

Living Along the Ganges

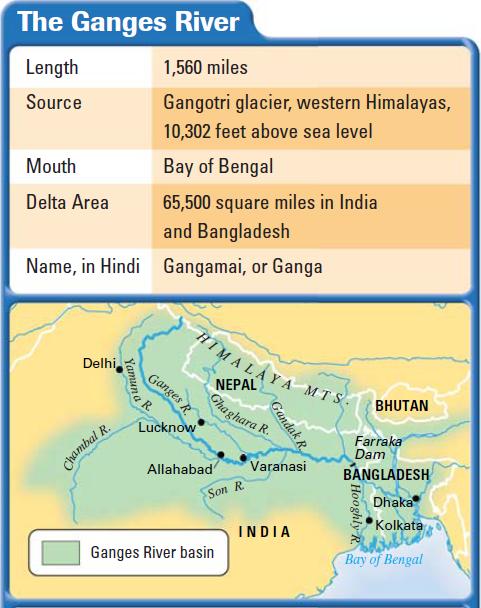

The Ganges is the most well-known of all the South Asian rivers. It flows more than 1,500 miles from its source in a Himalayan glacier to the Bay of Bengal. Along the way, it drains a huge area nearly three times the size of France. This area is home to about 350 million people. Although it is shorter than both the Indus and Brahmaputra rivers, the impact of the Ganges on human life in the region is enormous.

A SACRED RIVER

The Ganges is extremely important for the livelihood of Indians. It provides water for drinking, farming, and transportation. Just as important, though, is the spiritual significance of the river. The Ganges is known in India as Gangamai, which means “Mother Ganges.” In Bangladesh, where the Ganges joins the Brahmaputra, the river is called the Padma. According to Hindu beliefs, the Ganges is a sacred river that brings life to its people. As you read above, the Hindus worship the river as a goddess, and they believe its waters have healing powers.

Many temples and sacred sites line the banks of the Ganges. In some places, wide stone steps lead down to the water. Pilgrims come from all parts of the world to drink and bathe in its waters. They also come to scatter the ashes of deceased family members on the river.

At Varanasi (shown at right), one of the most sacred sites on the Ganges, thousands of people gather every day. As the sun rises, Hindu pilgrims enter the water for purification and prayer. They float baskets of flowers and burning candles on the water, as bells ring and trumpeters blow on conch shells. It is a daily celebration of their faith in the Ganges and its sacred waters.

A POLLUTED RIVER

Unfortunately for the people of India, the Ganges is in trouble. After centuries of intense human use, it has become one of the most polluted rivers in the world. Millions of gallons of raw sewage and industrial waste flow into the river every day. The bodies of dead animals float on the water. Even human corpses are thrown into the river. As a result, the water is poisoned with toxic chemicals and deadly bacteria. Thousands of people who bathe in the river or drink the water become ill with stomach or intestinal diseases. Some develop life-threatening illnesses, such as hepatitis, typhoid, or cholera.

Since 1986, the Indian government has tried to restore the health of the river. Plans have called for a network of sewage treatment plants to clean up the water and for tougher regulations on industrial polluters. So far, however, progress has been slow. Few of the proposed treatment plants are in operation, and factories and cities are still dumping waste into the river.

Pollution in the Ganges remains an enormous problem. It will take a great deal of time, effort, and money to clean up the river.

It will also require a change in the way people view the river. According to many Hindu believers, the Ganges is too holy to be harmed by pollution. If there is a problem with the water, they believe that “Mother Ganges” will fix it.

Controlling the Feni River

Just as the Ganges is the lifeblood of India, the rivers of Bangladesh are crucial to that country's survival. Many rivers emerge from the Chittagong Hills in the southeast. One of these rivers is the Feni, which flows into the Bay of Bengal just east of the huge delta that makes up most of the southern part of the country. The Feni begins as a small hill stream, but it becomes a wide, slow-moving river by the time it enters the bay.

A RIVER OVERFLOWS

The Feni flows through a low-lying coastal plain that borders the Bay of Bengal before it reaches the sea. This flat, marshy area is subject to flooding during the wet season. At that time, monsoon rains swell the river and may cause it to overflow its banks. Also a problem are the cyclones that sweep across the Bay of Bengal. They bring high waters—called storm surges—that swamp low-lying areas.

Over the years, storm surges at the mouth of the Feni River have caused tremendous hardship. Sea water surges up the river and onto the coastal flatlands. Villages and fields are flooded, causing great destruction. On smaller streams, villagers sometimes build earthen dikes to block the water and protect their farmlands. But such structures are not effective against the flooding of large rivers.

In the 1980s, engineers in Bangladesh proposed building an earthen dam for the Feni. Closing the Feni to build the dam would be very difficult, though. The mouth of the river is nearly a mile wide, posing major problems for dam construction. The cost of building such a dam would also be enormous. A poor country like Bangladesh has limited financial and technological resources.

USING PEOPLE POWER

Bangladesh did have one key asset for such a project—abundant human resources. With its large population, the country had plenty of unskilled workers available for construction work. To help plan the job, Bangladesh hired engineers from the Netherlands. As you read in Unit 4, the Dutch have had great experience in flood control.

From the beginning in 1984, the project emphasized the use of cheap materials and low-tech procedures. The first step was to lay down heavy mats made of bamboo, and reeds weighted with boulders. This was done to prevent erosion of the river bottom.

Workers piled more boulders on top and then covered them with clay-filled bags. After six months' work, they had built a partial closure across the mouth of the Feni River.

At that point, gaps in the wall still allowed water to flow in and out. Engineers had chosen February 28, 1985—the day of lowest tides—as the day to close the river. When the tide went out, 15,000 workers rushed to fill in the gaps with clay bags. In a seven-hour period, they laid down 600,000 bags. When the tide came back, the dam was closed.

COMPLETING THE DAM

After that, dump trucks and earthmovers added more clay to raise the dam to a height of 30 feet. Then, workers placed concrete and brick over the sides of the dam and built a road on top. Bangladesh now had the largest estuary (an arm of the sea at the lower end of a river) dam in South Asia. But a crucial question remained—would the dam hold against a major storm?

The test came three months later, when a cyclone roared into the Bay of Bengal. A storm surge hit the dam, but the dam held. The lands and villages behind the dam were spared the worst effects of the storm. The success of the Feni River closure offers hope for similar solutions in other low-lying areas of Bangladesh and South Asia.