Burkina Faso

POPULATION: 17.42 million (2014)

AREA: 105,869 sq. mi. (274,200 sq. km)

LANGUAGES: French (official); Mossi, Dyula, many local languages

NATIONAL CURRENCY: CFA Franc

PRINCIPAL RELIGIONS: Muslim 50%, traditional 40%, Christian 10%

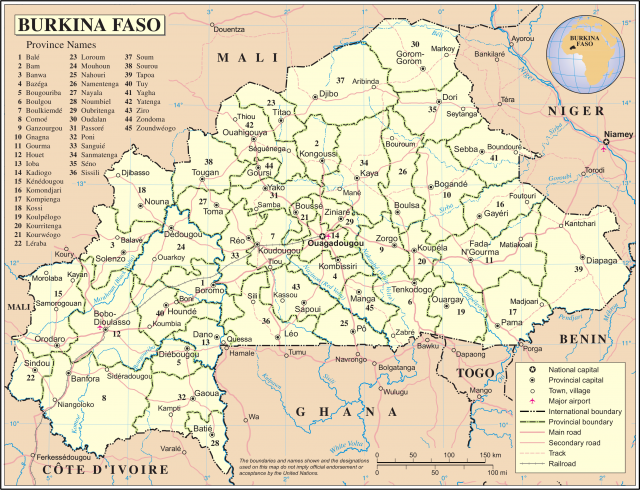

CITIES: Ouagadougou (capital), 1,100,000 (2000 est.); Bobo-Dioulasso, Koudougou, Ouahigouya, Kaya, Banfora

ANNUAL RAINFALL: Varies from 40 in. (1,000 mm) in the south to less than 10 in. (250 mm) in the north

ECONOMY: GDP $12.54 billion (2014)

PRINCIPAL PRODUCTS AND EXPORTS:

- Agricultural: peanuts, livestock, cotton, sesame, sorghum, millet, maize, rice, shea nuts

- Manufacturing: cotton tint, food and beverage processing, soap, agricultural processing, cigarettes, textiles

- Mining: gold, manganese, limestone, marble, antimony, copper, nickel, bauxite, lead, phosphate, zinc, silver

GOVERNMENT: Independence from France, 1960. President elected by universal suffrage. Governing bodies: Bicameral national legislature—Assemblee des Deputes Populaires and Chambre des Representants.

HEADS OF STATE:

- 1980–1982 Colonel Saye Zerbo

- 1982–1983 Surgeon-Major Jean-Baptiste Ouedraogo

- 1983–1987 Captain Thomas Sankara

- 1987– President Captain Blaise Compaore

ARMED FORCES: 5,800 (1998 est.) Compulsory 18-month service.

EDUCATION: Compulsory for ages 7–13; literacy rate 19%

Burkina Faso, formerly known as Upper Volta, is a landlocked nation in western Africa. It is one of many states formed after the breakup of the French colonial empire. Although the nation went through periods of unrest after gaining independence in 1960, it has become a relatively stable country. The name Burkina Faso means “Land of the Honorable People” or “Homeland of the Proud People.”

GEOGRAPHY AND ECONOMY

Burkina Faso is a fairly flat country dominated by forests and savannas. Towering mounds of red termites dot the grasslands. The northern region is quite dry, as is the country's southern edge, averaging only about 5 inches of rain per year. The central and southern regions of the country are generally much wetter, receiving 2 to 3 feet of rain annually. In all areas, the rains tend to fall in brief, heavy storms that can wash away crops and topsoil.

Most of the population makes a living from agriculture, raising livestock, cotton, and food crops. Livestock and related products such as meat and leather contribute about one-third of Burkina Faso's export revenues. Another important export is labor. About a million Burkinabe live in neighboring IVORY COAST and send money home to relatives. Many more residents leave the country to find work on a temporary or seasonal basis.

The small amount of industry in Burkina Faso is mainly concentrated in towns such as its capital, Ouagadougou. For years most industries were owned by the state, but since 1991 many have been transferred to private ownership. The nation's gold mining industry has grown in importance since the 1980s. However, a lack of funding and infrastructure, such as roads and railroads, has hindered the mining of other minerals.

HISTORY AND GOVERNMENT

Unlike much of western Africa, Burkina Faso was untouched by European influence until the late 1890s. Then the French gained control of the area and ruled it from 1904 to 1960.

Precolonial and Colonial History

Before the arrival of Europeans, many small household- and village-based societies occupied the western portion of what is now Burkina Faso. MOSSI people from the south invaded the central and eastern areas of the region during the 1400s. According to tradition, the Mossi were descended from Naaba Wedraogo, the son of a princess of a town in northern GHANA. For many years, the Mossi moved throughout the region conquering new areas. In the late 1400s and early 1500s they established several kingdoms, the most important of which were Ouagadougou and Yatenga. The kingdoms featured complex political and religious systems.

The French arrived in the region in the 1870s. Over the next decades, they formed alliances with African societies that lived around the Mossi. In 1896 and 1897 the French defeated the Mossi and other independent peoples nearby. Naming the region Upper Volta, the French declared it a military zone in 1899. A few years later, they incorporated the area into the colony of Upper Volta-Senegal-Niger. The French colonial government introduced taxes and a military draft and forced the Africans to work for little or no pay. This treatment led to several rebellions—especially among the western peoples. The French crushed these uprisings and destroyed all traces of African rule.

Upper Volta became a separate colony in 1919. However, the French soon found that its only economic value was as a source of laborers for other colonies. Within 13 years, they divided Upper Volta's territory between the colonies of Ivory Coast, NIGER, and Soudan (now MALI). After World War II, France granted new political rights to its African colonies. In response to pressure from Mossi leaders, it made Upper Volta a separate colony again in 1947.

In 1958, when France allowed each of its African colonies to vote for independence, Upper Volta chose to remain a largely self-governing French colony. Maurice Yameogo, the head of Upper Volta's main political party, the Rassemblement Democratique Africain (RDA), was elected president of the Council of Ministers. In 1960 he banned the main opposition party. Later that year Upper Volta requested and received independence from France. With no organized opposition, Yameogo was chosen president, and the RDA became the dominant political force in the country.

The Early Republics

Yameogo was reelected in 1965 with nearly 100 percent of the vote. He then tried to place tight restrictions on government spending. Trade unions protested the restrictions by calling a general strike in January of the following year. Amid the unrest, the army overthrew Yameogo's government, and Colonel Sangoule Lamizana took over the presidency. Lamizana ended Yameogo's ban on political activity. However, when violence erupted between competing political groups, Lamizana re-imposed the ban. He announced military rule but promised to restore civilian government after four years.

Free elections were held in 1970, and a new constitution created Upper Volta's Second Republic. The constitution provided for Lamizana to continue as president for four years, and it called for the military to participate in all political institutions. A new crisis arose in 1974, when Prime Minister Gerard Ouedraogo lost support in parliament but refused to resign. Lamizana again proclaimed military rule and banned political parties. When he tried to establish a single political party for the nation the following year, the trade unions responded angrily with another general strike. Lamizana backed down, and in January 1976 he appointed a new government consisting mostly of civilians.

In 1977 another constitution established the Third Republic. It limited the number of political parties to the top three vote-winners in the national elections that followed. Lamizana was reelected president. However, no single political party won control of a majority of the seats in the assembly. The result was a weak government that once again ran into difficulty with the trade unions. A strike in late 1980 was followed by a military coup led by Colonel Saye Zerbo. However, friction grew between leaders of the military government, and Zerbo himself was overthrown in late 1982.

Communist Rule and The Fourth Republic

The leaders of the coup created a ruling body called the Council for the People's Salvation (CSP). The CSP named Surgeon-Major Jean-Baptiste Ouedraogo president and Captain Thomas Sankara prime minister. Sankara quickly abandoned the nation's allies in the West and established ties with developing countries such as Libya, Cuba, and North Korea. Critics within the government arrested Sankara in May 1983, but Captain Blaise Compaore freed him in August and overthrew the CSP.

Backed by communist groups, Sankara adopted a foreign policy that rejected Western governments. To symbolize the country's break with its colonial, pro-Western past, Sankara changed Upper Volta's name to Burkina Faso in 1984. He established “revolutionary councils” at all levels of society to try to establish a totalitarian system with himself at its head. However, as Sankara began using force to maintain power, opposition to his rule increased. He eventually lost the support of his own people, and in October 1987 Captain Compaore ordered his troops to kill Sankara.

Compaore reversed many of Sankara's policies and rejected the previous government's communist ties. In 1991 a new constitution was approved reestablishing multiparty politics and direct election of the president and National Assembly (Assemblee des Deputes Populaires). Later that year Compaore was elected as the first president of the Fourth Republic. However, the opposing parties refused to participate in the election because they felt the government was not protecting their rights. In response, Compaore ended persecution of his political opponents and called new elections in April 1992. He was again elected and continues to serve as president of the country. However, his government has not always responded well to criticism, and in 1995 an opposition leader was jailed for insulting Compaore.

PEOPLES AND CULTURES

Burkina Faso is home to many different ethnic groups. The largest of these, the Mossi, make up nearly half of the population. Other major groups include the FULANI, the Gulmanceba, and the Gurunsi. The social organization of most of these peoples is based upon the lineage—a kind of extended family. Each lineage traces its origins back to a common, often mythical, ancestor and forms a group that usually lives in a particular village neighborhood. Most lineages trace descent through male family members.

Older members of society are treated with great respect. In many places the oldest male member of the family makes all of the important decisions for his family. The oldest male in a lineage is in charge of dealing with local gods. In many cases, he also has responsibility for enforcing laws and serves as a peacemaker. Although women hold few leadership posts or religious offices, they do exercise informal influence.

A male political leader, a naaba, holds a sacred position among the Mossi, the Gulmanceba, and the Gurunsi. In addition to his special spiritual powers, the naaba owns the land and its inhabitants. At one time he could require subjects to serve him as warriors and laborers and to pay tribute. The naaba protected his power by granting distant villages and lands to certain princes and to descendants of the founder of the empire.

The peoples of Burkina Faso share a rich religious heritage. In traditional agricultural religions, the spirit of the earth and the spirits of ancestors are particularly important. These spirits ensure that people follow custom and tradition, and they provide the community with rain, fertility, and health. The spirit of heaven is also prominent in local religions. Heaven, which made the world, is responsible for rain, fate, and children's souls.

Bush spirits rule the land outside the villages. Besides controlling the abundance of game and the fortune of hunters, they also punish wrongdoers. These spirits appear in the form of animals—most often reptiles—who serve the lineage elders. Lineage members must not kill or eat these animals because they may help elders find water or lead them to victory over enemies. The spirits inhabit prominent places in nature such as hills, rocks, lakes, and caves.

Fortune-tellers play an important part in traditional beliefs. They give people advice on what actions to take in everyday life, and they teach them to use nature's powers for their own purposes. However, WITCHCRAFT or other types of magic that cause damage or trouble are generally avoided. Although many people still follow traditional religious beliefs and practices, some of Burkina Faso's people have adopted Christianity, and about half the nation's population is Muslim. (See also Colonialism in Africa, Unions and Trade Associations.)