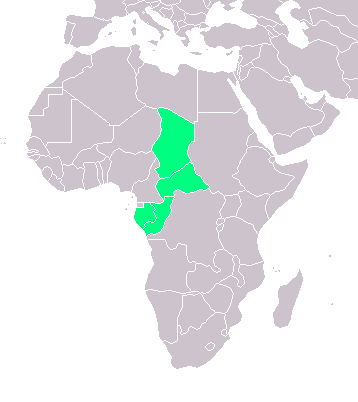

French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa was a French colony in the late 1800s and early 1900s, located in the area now occupied by the countries of CAMEROON, GABON, the CONGO (BRAZZAVILLE), the CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, CHAD, and SUDAN. France administered the colony in a heavy-handed and inefficient manner. As a result, they did not get much benefit from their control over the region.

Early History

The first major French settlement in equatorial Africa was Libreville, a coastal city established in 1849 as a home for freed slaves. French explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza led several expeditions up the CONGO RIVER in the 1870s and 1880s. He signed treaties with local chiefs making much of the area a French protectorate. Instead of forcing the indigenous peoples to submit to French rule, Brazza promised them greater trading opportunities if they would cooperate with him. For a time the colony ran smoothly. But in the 1890s, when France attempted to gain control of territory to the north, several local rulers resisted the takeover. French troops were brought in to conquer the region, but northward expansion of the colony proceeded slowly.

France refused to invest in the vast, thinly populated, and unstable colony. Seeking other ways to make money, the French colonists granted private companies 30-year leases to exploit the wealth of the region. In return for a small fee, these firms, called concessionary companies, were given large areas of land from which they could harvest ivory and wild rubber. The companies were also allowed to collect taxes and to open the area to trade. However, they abused their rights, imposing heavy taxes on local populations, forcing people to work for little or no pay, and imprisoning local women and children. They became known for their extremely brutal treatment of workers.

The concessionary system did not work for the French for other reasons. The ivory supply ran low and, after 1911, competition from plantation-grown rubber from Malaysia made the rubber business unprofitable.

In addition, neither the companies nor the colonial officials were willing to spend money for the roads and other systems needed to bring goods to market and to supply operations with equipment and workers.

Discontent and Political Turmoil

In 1908 France made French Equatorial Africa a federation of territories modeled after FRENCH WEST AFRICA. The new federation consisted of four territories: Gabon, Congo (modern-day Congo, Brazzaville), Oubangui-Chari (modern-day Central African Republic), and Chad. France hoped that this reorganization would strengthen its central authority in the region.

However, the French were slow to change the concessionary system, and local uprisings occurred throughout the 1920s and 1930s. One such conflict, called the war of Kongo-Warra, lasted several years. It spread from eastern Cameroon as far north and west as Chad, and claimed tens of thousands of lives. At the same time, Africans in the colony were becoming more politically active and more determined to resist French control.

In the 1930s the towns of French Equatorial Africa began to grow at an increasing rate, drawing people from the surrounding countryside. The new cities became centers of African resistance. In an attempt to contol the indigenous population, the government separated black and white neighborhoods in cities and provided services and equipment only to white areas. Despite such efforts, a new and thriving black urban culture developed in the cities.

War and Independence

During World War II, Felix EBOUE, the governor of Chad, convinced most of French Equatorial Africa to support Charles DeGaulle's Free French Forces rather than Nazi-occupied France. To ensure that war supplies would be produced for the Allies, colonial officials strengthened forced labor laws. This, along with the arrival of new European settlers, produced more discontent among the indigenous population.

Near the end of the war, a conference was held in BRAZZAVILLE to discuss the future role of France in Africa. Over the next several years Africans gained new freedoms. A small percentage of the population received the right to vote, and Africans were allowed to form their own political parties. At first these parties were controlled by politicians who worked closely with the colonial authorities. However, as more Africans gained the right to vote, political differences between African and European parties widened. In an attempt to control politics in the colony, French authorities formed secret ties with African leaders. They also stirred up rivalries between ethnic groups to weaken the power of local parties. Election fraud became commonplace, and parties often gained votes by threatening voters.

In the late 1950s, the territories of French Equatorial Africa prepared to split into separate independent nations. Aggressive and powerful politicians, such as Gabon's Leon Mba and David Dacko of Chad, emerged as the leaders of some territories. In other territories local groups struggled for control. In Brazzaville, Congo, conflicts between northern supporters of Fulbert Youlou and southern backers of Jaques Opangault led to the massacre of hundreds of people. Such violent unrest would become a common part of life in many of the nations that emerged from French Equatorial Africa. (See also Colonialism in Africa.)