Russia and the Republics: Central Asia

A HUMAN PERSPECTIVE Central Asia has inspired the dreams of many adventurers—and presented them with many dangers. In the 19th century, agents of the mighty British Empire found that even they were not safe there. In 1842, two British officers were captured in the Central Asian city of Bukhoro. For months, the city's ruler kept the men in an underground bug-pit that swarmed with ticks, rats, and scaly vermin. In June of that year, he forced the two officers to dig their own graves and then beheaded them. In spite of the dangers, people have journeyed across Central Asia throughout history.

A Historical Crossroads

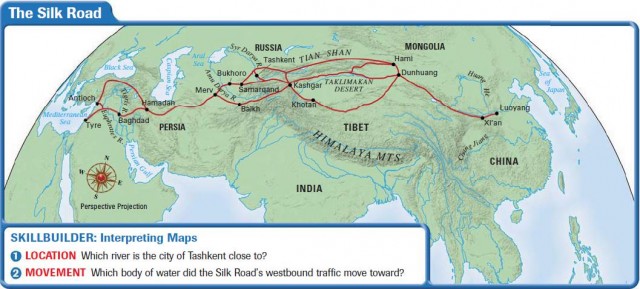

Today, Central Asia consists of five independent republics: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Travelers first began to make their way across the region in large numbers around 100 B.C. Many of them joined caravans making the 4,000-mile journey between China and the Mediterranean Sea.

THE SILK ROAD

Traders called this route the Silk Road, after the costly silk they bought in China. In addition to silk, traders carried many other goods on their horses and camels. These included gold, silver, ivory, jade, wine, spices, amber, linen, porcelain, grapes, perfumes—even ostriches and acrobats. The Silk Road also became a route for spreading ideas, technology, and religion.

Traffic on the Silk Road slowed in the 14th century, giving way to less expensive sea routes. Even so, you can still experience the legacy of the Silk Road in the magnificent cities—such as Samarqand and Bukhoro—built to take advantage of the trade.

THE GREAT GAME

Interest in Central Asia exploded again in the 19th century when Great Britain and the Russian Empire began to struggle for control of the region. Russian troops were moving southward, and British leaders wanted to stop the advance before the troops could threaten Britain's possessions in India.

Both sides recruited daring young officers who made journeys through the region in disguise. These officers worked to create maps of Central Asia and to win local leaders to their side. Arthur Connoly—one of the British officers executed in Bukhoro—called this struggle between the two empires the Great Game.

By the end of the 19th century, the Russian Empire had won control of Central Asia. In the 1920s, the Soviet Union took control and governed the region until 1991. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Central Asian republics have been independent.

An Uncertain Economic Future

In Chapter 15, you read about the problems caused by Soviet irrigation programs in Central Asia. Other Soviet programs have also caused problems in the region.

NUCLEAR TESTING

Until the late 1980s, the Soviet nuclear industry was the economic mainstay of Semey (renamed Semipalatinsk), a city in northeastern Kazakhstan. Between 1949 and 1989, scientists exploded 470 nuclear devices in “the Polygon,” a vast nuclear test site southwest of Semey.

The nuclear tests were so close to Semey that citizens could see the mushroom clouds of the above-ground explosions. Later, underground explosions cracked walls in towns 50 miles away. The testing caused widespread health problems. Winds spread nuclear fallout over a 180,000-square-mile area, exposing over a million people to dangerous levels of radiation. Exposure caused dramatic increases in the rates of leukemia, thyroid cancer, birth defects, and mental illness. Although testing at the site ended in 1989, the harmful effects of radiation will continue for years to come.

PETROLEUM AND PROSPERITY

More hopeful is the potential for oil to bring wealth to Central Asia. Regional leaders see great promise in the oil and gas reserves of the Caspian Sea. In addition, engineers have recently discovered oil fields in Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. These discoveries have triggered what many are calling the new “Great Game,” as nations all over the world begin to compete for profits from the region's resources.

For Central Asia's resources to benefit its people, however, leaders must first establish stable political and legal institutions. The cultural geography of Central Asia, though, will make this goal especially difficult to achieve.

Cultures Divided and Conquered

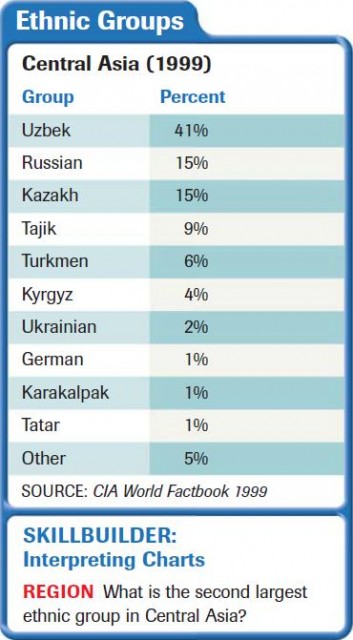

Central Asia has a large number of ethnic groups, as the chart to the right shows. Before the Russian Revolution, each group lived in a particular region where it could follow its own way of life.

SOVIETS FORM NATIONS

When the Soviets took control of Central Asia, they used the differences among the ethnic groups to establish their own authority in the region.

Soviet planners carved the region into five new nations that corresponded to the largest ethnic groups—Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Tajik, Turkmen, and Uzbek. However, when they drew the borders of these nations, they deliberately left large numbers of one ethnic group as minorities in the neighboring republics of other ethnic groups.

That explains why Uzbeks form about 24 percent of the population of Tajikistan and why two of the major cities inside Uzbekistan, Samarqand and Bukhoro, are populated by ethnic Tajiks. Ethnic Uzbeks also make up 9 percent of Turkmenistan's and nearly 14 percent of Kyrgyzstan's populations. Soviet leaders tried to prevent opposition to their rule by using the tensions that existed among these different groups.

LANGUAGE AND RELIGION

Although the peoples of Central Asia are divided by a number of ethnic and political loyalties, there are unifying forces in the region as well. Islam, which was brought by Muslim warriors from Southwest Asia in the 8th and 9th centuries, is one of the strongest. Also, most Central Asians speak languages related to Turkish. Many people also speak Russian, once the region's official language.

The Survival of Tradition

Central Asia endured decades of upheaval under Russian and Soviet rule. Even so, many of the region's traditions have survived.

NOMADIC HERITAGE

The expansive grasslands of Central Asia are ideal for nomadic peoples. Nomads are people who have no permanent home. As seasons change, they move from place to place with their animals in search of food, water, and grazing land.

During the years of Soviet control, the number of nomads in Central Asia decreased dramatically as officials forced people onto collective farms. Even so, you can still find nomads in the region. In central Kyrgyzstan, for example, herders set up their tents near Lake Song-Kol during the summer months. They bring their animals there to graze on the lush pastures of the valley.

Because they are always on the move and must carry what they own, nomads have few possessions. They usually carry what is most useful. Even so, many of the possessions of Central Asia's nomads are both useful and beautiful.

YURTS

Among the most valuable of the nomads' possessions are their tents—called yurts. Yurts are light and portable. They usually consist of several layers of felt stretched around a wooden frame, often made of willow. The outermost layer of felt is coated with the waterproof fat of sheep.

As the photo on page 378 shows, the inside of a yurt can be stunningly beautiful. To block the wind, nomads hang reed mats, intricately woven with the grasses of the steppe. For storage, they suspend woven bags on their tent walls. The inlaid wooden saddles of their horses and their carved daggers also ornament the yurt.

Perhaps the most beautiful and useful of all the yurt's furnishings are the handwoven carpets. Their elaborate designs, colored with natural plant and beetle dyes, have made the carpets famous. Nomads use them for sleeping, or as floor coverings, wall linings, and insulation.

PRESERVING TRADITIONS

The nomadic lifestyle of the peoples of Central Asia is not nearly as widespread as it once was. But many people are working hard to preserve the tradition. One group has organized a network of shepherds' families in Kyrgyzstan who are willing to take in guests. In this way, tourists can experience the daily life of the shepherds, who, in turn, receive a source of income for their families. Central Asians will benefit greatly from such imaginative and productive uses of their traditions.