Russia and the Republics: Transcaucasia

A HUMAN PERSPECTIVE Throughout history, human beings have migrated through Transcaucasia, which today consists of the republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. Recent discoveries have shown just how early such migrations began. In the summer of 1999, a team of scientists discovered two 1.7-million-year-old human skulls in the Transcaucasian republic of Georgia. They were the oldest human fossils found outside Africa. Reports suggest that the skulls could belong to the first people to have migrated from Africa.

A Gateway of Migration

People have long used Transcaucasia as a migration route, especially as a gateway between Europe and Asia. Trade routes near the Black Sea led to the thriving commercial regions of Mediterranean Europe. And trade routes leading to the Far East began on the shores of the Caspian Sea.

A VARIETY OF CULTURES

Because of the presence of so many trade routes, Transcaucasia has been affected by many different peoples and cultures. Today, more than 50 different peoples live in the region.

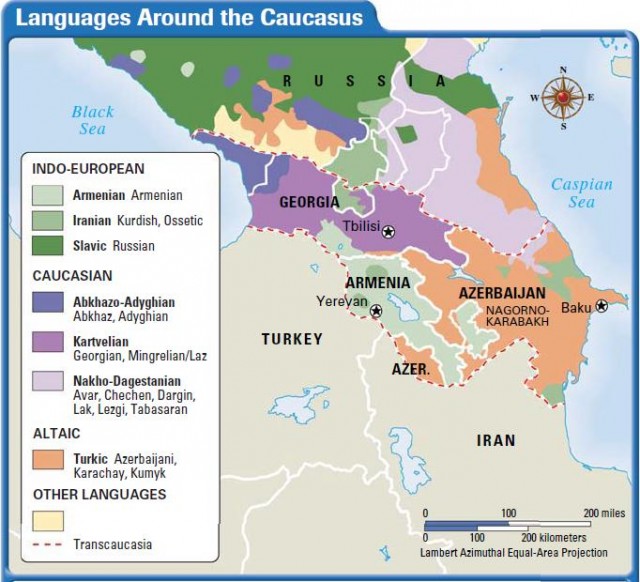

Migrants brought a great variety of languages to the region. Arab geographers called the region Jabal Al-Alsun, or the “Mountain of Language.” The Indo-European, Caucasian, and Altaic language families are the region's most common.

MIGRATION BRINGS RELIGIONS

The people of Transcaucasia follow a number of different religions. However, most of the region's people belong to either the Christian or the Islamic faith.

These faiths arrived in the region at an early date, because Transcaucasia is close to the areas in Southwest Asia where the two religions began. Armenia and Georgia, for example, are among the oldest Christian states in the world. Armenia's King Tiridates III converted to Christianity in A.D. 300. A year later, he made his state the first in the world to adopt Christianity.

Not long after the 7th-century beginnings of Islam in Southwest Asia, Muslim invaders stormed into the southern Caucasus and converted many Transcaucasians to Islam. Today, the great majority of Azerbaijan's people are Muslim.

CONFLICT

The region's diverse population has not always lived together in harmony. Tensions seldom erupted into open hostility under the rigid rule of the Soviets.

However, after the collapse of the USSR in 1991, tensions among different groups have resulted in violence. Civil war broke out in Georgia, and Armenia fought a bitter war with Azerbaijan over a disputed territory called Nagorno-Karabakh.

The story of conflict is not new to Transcaucasia. Its history of conflict, as you will read below, can be explained, in part, by its location.

A History of Outside Control

Over the centuries, Transcaucasia has been a place where the borders of rival empires have come together. Imperial armies have repeatedly invaded the region to protect and extend those borders.

CZARIST AND SOVIET RULE

In the 18th century, the troops of the Russian Empire joined the list of invaders. Russia's southward expansion had begun as early as the 1500s, but it was only in the 1700s that the czar's army began making progress south of the Caucasus Mountains.

The inhabitants of the region resisted the Russians, but the czar's troops prevailed. By 1723, Peter the Great's generals had taken control of Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. In 1801, Russia annexed Georgia. In 1828, Russian armies took control of a large stretch of Armenian territory, including the plain of Yerevan. By the late 1870s, the czar's troops had added Transcaucasia to the Russian Empire.

After the Russian Revolution in 1917, the Transcaucasian republics enjoyed a brief period of independence. By the early 1920s, however, the Red Army—the name of the Soviet military—had taken control of the region.

In the decades following the Soviet takeover, the people of Transcaucasia experienced the same painful economic and political changes as the rest of the Soviet Union. Many people lost their lives in famines triggered by the shift to collective farming or were killed because of their political beliefs. The republics of Transcaucasia regained their political independence in 1991 after the fall of the Soviet Union. Since then, the region's leaders have struggled to rebuild their nations' economies.

Economic Potential

Today, economic activity in the Transcaucasian republics ranges from the tourism and wine industries of subtropical Georgia to large-scale oil production in Azerbaijan.

AGRICULTURE AND INDUSTRY

Although much of Transcaucasia's terrain is mountainous, each of the republics has a significant agricultural output. Transcaucasians have taken advantage of the region's climate and the potential of the limited amount of land fit for farming.

The humid subtropical lowlands and foothills of the region are ideal for valuable crops such as tea and fruits. Grapes are one of the most important fruit crops. Georgians use the grapes cultivated along their Black Sea coast to produce their famous wines. Georgia's mild climate also once fueled a profitable tourist industry.

There was little industry in Transcaucasia before the Soviet Union took control of the region. Soviet planners transformed Transcaucasia from a largely agricultural area into an industrial and urban region.

A number of industrial centers built by the Soviets continue to produce iron, steel, chemicals, and consumer goods for the region's economy. But today, the oil industry is most important. The oil industry has an impact not only on oil-rich republics, such as Azerbaijan. It also affects Armenia and Georgia because oil producers want to build pipelines across their territory to bring the oil to market.

LAND OF FLAMES

The significance of oil in the region has a long history. In fact, the name Azerbaijan means “land of flames.” The republic's founders chose the name because of the fires that erupted seemingly by magic from both the rocks and the waters of the Caspian Sea. The fires were the result of underground oil and gas deposits.

DIVIDING THE CASPIAN SEA

Since the breakup of the Soviet Union, Azerbaijan and the other four countries bordering the Caspian Sea have argued about whether the Caspian is an inland sea or a lake. The resolution of this argument will decide how resources are divided among the five countries.

If the Caspian is a sea, then each country has legal rights to the resources on its own part of the sea bed. If it is a lake, the law says that most of the resource wealth must be shared equally among each of the countries. Azerbaijan, with large reserves off its coast, says the Caspian is an inland sea. Russia, with few offshore reserves, insists that the Caspian is a lake.

The oil industry has given the region's people hope for a better life. But oil revenue has benefited few Transcaucasians. Many continue to live in poverty.

Modern Life in Transcaucasia

Although times are tough for many, the region has much to offer, including a well-educated population and a reputation for hospitality.

AN EDUCATED PEOPLE

The educational programs of the Soviet Union had a largely positive impact on its people. At the time of the Russian Revolution, only a small percentage of Transcaucasia's population was literate. Communist leaders decided to train a new generation of skilled workers who would be prepared to undertake the tasks of industrial development and modernization. They succeeded, as literacy rates in Transcaucasia rose to nearly 99 percent, among the highest in the world. Today, high quality educational systems remain a priority for Transcaucasians.

HOSPITALITY

In their quest for a modern system of education, Transcaucasians have not forgotten the value of their traditions. Among the most important are the region's mealtime celebrations.

The Georgian supra, or dinner party, is one of the best examples of such gatherings. The word supra means tablecloth but also refers to any occasion at which people gather to eat and drink.

A supra involves breathtaking quantities of food and drink. Meals begin at a table spread with a great number of cold dishes. Two or three hot courses and fruit and desserts follow those. Georgians add locally grown foods, such as grated walnuts, garlic, and an array of herbs and spices to their recipes. And they are able to serve meals with remarkable freshness, thanks to the region's mild climate.

In addition to food and drink, a supra is accompanied by a great number of toasts, short speeches given before taking a drink. Georgians take the toasts very seriously because they show a respect for tradition, eloquence, and the value of bringing people together—a goal of great importance for the future of the region.