The Arctic

At the other end of the world, things are very different. The Antarctic continent is surrounded by the Southern Ocean, the worlds wildest ocean, which roars round the Earth untrammelled by land. But while the Antarctic is land surrounded by water, the Arctic is water surrounded by land. The pole itself is merely a spot in the ocean, usually icy but some-times watery. As we saw in Chapter 6, the Arctic Ocean is probably the most sluggish in the world. It receives the least solar energy to get things going. And it is connected only tenuously to the rest of the world ocean, via the Bering Strait between Alaska and Siberia, and two bigger seaways to either side of Greenland. So it takes in only limited amounts of warmer water from further south.

Unlike the Antarctic, the Arctic has a native human population and the lands that surround it are part of the developed world. They are the northern extremities of Norway, Denmark, Russia, Canada and the US. (Greenland is more or less independent but is in principle part of Denmark.) Some of its peoples, the Inuit or Eskimos, the Lapps and their Siberian allies, have been there for thousands of years and have adapted physically to conditions there. Other northern communities are of more recent origin and are more dependent upon modern technology to stay comfortable and alive.

In contrast to the Antarctic, large areas of the Arctic are in use. Oil and gas are pumped, especially from Alaska and Russia, minerals are mined, and other mostly pretty primary industrial activities go on. In Russia especially, some mining has led to major pollution. In addition, all this activity means that the Arctic contains some substantial towns. Tromso in Norway has a population of 50,000 and boasts, amongst other attractions, the worlds most northerly brewery, university and planetarium.

Greenland, the frozen island

Of all the Arctic lands, Greenland is the most significant in size and tor the worlds climate, and most of it lies to the north of the Arctic Circle. It can be regarded as the northern mini-me to the Antarctic. It is only a seventh of the size of the Antarctic continent, with an area of just over 2.1 million square kilometres. But like Antarctica, it is covered in deep ice sheets of immense age.

The Greenland ice cap contains about 2.5 million cubic kilometres of ice. In round figures this means that Antarctica contains 90 percent of the worlds ice and Greenland the rest. All the other glaciers in the world are small by comparison.

The ice caps of Greenland are over 4km thick at their maximum depth. Their weight puts so much pressure on the rock below that it has bent downwards into a deep bowl shape, as has happened, too, in much of the Antarctic. In most of Greenland, the rocky basement beneath the ice is below sea level. A column of ice 4km high would put a pressure of over 4000 tonnes on every square metre of rock, because as the snow piles up, the ice lower down is compressed and becomes more dense.

As with the Antarctic ice, this vast amount of material has formed by snow tailing and being gradually crushed beneath successive years of snowfall on top. That means that it too can be used for finding out about the past. Drilling has already found ice as old as 200,000 years, from over 3km below the surface. The biggest and best samples are gathered from an evocatively named place called Summit, in the dead centre of the island. As this is the area from which ice flows outwards, it has the most undisturbed ice, all the way from the surtace down over 3km to solid rock. This ice is the prime database for the Earths climate in geologically recent time, and also tells us about other key environmental variables such as ocean current circulation.

Of course the burning question about the ice caps of both Greenland and the Antarctic is whether they will still be there in a few years, decades or centuries. What are we to make of tales of massive areas of ice breaking off both of these land masses and melting as they float away from the pole?

Part of the answer is that this is a natural process that has always gone on. However, modelling carried out by British environmental scientists suggests that a 3°C rise in average temperatures would melt the Greenland ice cap in time. Some forecasts for global warming contain far bigger possible rises than this. Melting all the ice in Greenland would increase sea level by perhaps 7m, endangering many of the worlds most important cities and a good percentage of its population. As researchers point out, once the ice was gone, Greenland would be far lower-lying and the ice would not re-form any time soon even if global warming were halted or reversed.

…and its relatives

The other major islands of the Arctic are mostly in northern Canada and Russia. Most of them lie between North America and the pole. Their tangled geography is the reason why many European explorers got lost and never reappeared from missions to find the North-West Passage from Europe to Asia. Many of their names (Devon, Somerset, Victoria, Prince of Wales) reflect the high point of Victorian imperial ambition which was represented by the impractical plan for a sea route from Britain to its Pacific colonies. The area is so remote that substantial new islands went on being discovered in the Canadian Arctic into the 1960s, when aerial and then satellite photography finally produced comprehensive surveys.

The biggest of these islands is Baffin Island, now on the adventurous end of the tourist trail as a rock-climbing destination. Like the rest of the Arctic islands, it has been formed by vigorous glaciation and has the peaks, cliffs and fjords to prove it.

However, the most visited Arctic islands are almost certainly the Svalbard group. Politically part of Norway under an elaborate treaty whose signatories include China and Poland, the archipelago has Norwegian and Russian coal mines, but also boasts about 3000 polar bears. So it is fine for country walks for the energetic provided you remember to take a large gun and keep it visible. At a latitude of 80°N, the islands are only 1000km from the pole.

Around the ice: permafrost

The Arctic regions ecology is dominated by the cold. So it is not surprising that even where it is not covered in ice, its land area is often frozen solid tor long periods. Any soil that has been frozen tor more than two years is known as permafrost. That is the definition, but in practice much permafrost has been rock-solid since the last ice age. The miners digging tor coal on Svalbard tound permatrost hundreds of metres deep and the record is over 1km.

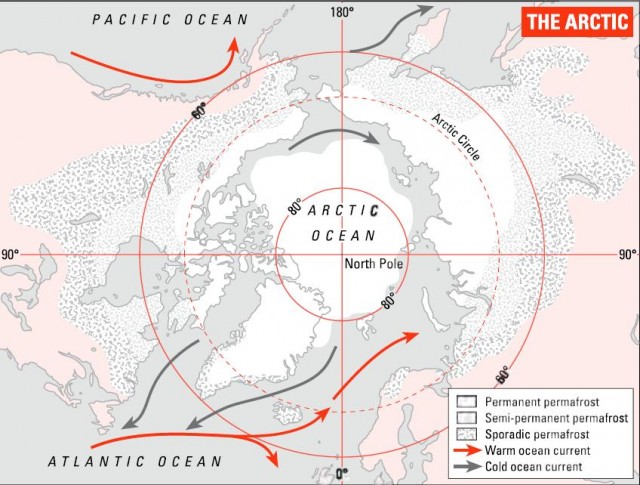

You have probably never seen permafrost, but it occupies about 25 percent of the land surtace ot the northern hemisphere. About 55 percent of the land in the northern hemisphere freezes for at least part of the year, but only a small part of the land in the southern hemisphere does so because of the dearth of large continents to the far south. As well as much of the Arctic, permafrost covers parts of the Himalayas and patches of the Rocky Mountains.

Scientists point out that despite its name, permafrost is often not very perma. It is often found below a surface layer of soil that melts in summer, making for treacherous conditions for buildings and pipelines.

In recent years, we have come to realize that permafrost ties up about 400 billion tonnes of stored carbon. Most of it is in the form of methane, which is three-quarters carbon by weight. These soils have been biologically active in the past, which means that they contain ancient carbon, which is supplemented by fresh supplies from the active layer of soil nearest the surface.

It global warming allowed the permafrost to melt, the released carbon would itself add massively to the greenhouse effect. Some forecasts suggest that this will happen in the present century. Human activity produces carbon dioxide emissions of “only” about 25 billion tonnes a year. So the effect of releasing even a small amount of the total in store would be huge. As well as altering the climate globally, melting permafrost would release many cubic kilometres of water now stored as ice. This would alter the northern landscape, such as its river systems, fundamentally.

Despite all this frozen land, the Arctic is no desert. Its characteristic ecology is tundra, a landscape dominated by small plants which succeed because the air is warmer nearer the ground. Further south come milder conditions which support forests, called taiga – like tundra, a Russian word.

Tundra is dominated by mosses, lichens and small shrubs, but it supports a much wider ecology including small mammals such as mink and big ones such as wolves. Polar bears, the most characteristic Arctic species, are adept at swimming and fond of fish, but are also happy to eat land animals including humans.

Arctic ecosystems are fragile. The extreme cold has its advantages for science. It means that all those mammoths stay preserved for thousands of years, perhaps with their DNA in such good condition that they can be cloned. But it also means that Arctic environments are especially difficult to conserve. Things happen slowly when the growing season is only about two months long. Damage that would repair itself quickly in a warm climate takes far longer to heal in cold regions. There are now proposals for a sea route from Europe to Asia via the north Russian coast, which would add to the pressure on Arctic environments, especially if it was introduced alongside more oil drilling in the area. New technology has made it possible to travel safely there, while reduced ice cover could make it economically attractive to move big ships on this route for several months a year.