Theater

Theater in Africa takes many different forms and comes from diverse roots. Indigenous customs, such as storytelling, ritual, dance, and masquerades, are the oldest types of theater on the continent. In North Africa and other areas dominated by Islamic culture, theater often includes reciting popular tales and acting out religious stories, such as the deaths of the grandsons of the prophet Muhammad. Since the arrival of Europeans, Africans have also staged plays in the style of Western theater—dramas and comedies based on scripts.

Today, African artists often combine various forms to create new styles of theater. For example, many modern African plays are Western in structure but include traditional elements. In many cases, African plays deal with controversial political and social issues.

Traditional Theater

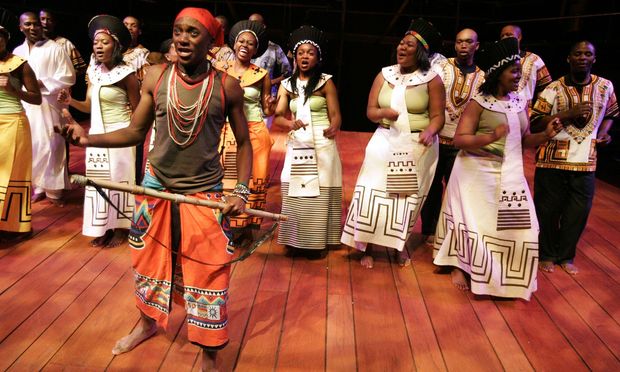

The types of performance that existed in Africa before the arrival of Europeans are generally referred to as traditional theater. Some traditional theater is performed for entertainment, such as the storytelling of the Akan people of GHANA. Other traditional theater has important religious and social meaning. Examples of such performances include the ancient ritual dramas and dances of the KHOISAN people of southern Africa; the spectacular masquerades performed in SIERRA LEONE, NIGERIA, and Ghana; and the songs and ritual stories acted out by the XHOSA and ZULU people in southern Africa.

Traditional theater in all African cultures shares certain features. It does not have a script or a “correct” version that performers must follow. Characters are not portrayed as individuals but as general types, such as the dishonest merchant, the prostitute, or the foreigner. Performances often criticize or make fun of political and social targets, such as corrupt chiefs or greedy prophets of foreign religions. Song, music, and dance are highly important elements of the performance.

African traditional theater is a group activity, often without boundaries between creators, performers, and audience. Unlike modern plays, traditional rituals and tales are not written by individual playwrights. They have been molded from the culture and customs of an entire community and are passed on by memory from generation to generation. Rather than taking place on a stage at a planned time and date, performances are part of the social and cultural activities associated with daily life and with major events such as birth, INITIATION RITES, hunting, marriage, SPIRIT POSSESSION, and death.

A good example of African traditional theater is the Koteba of MALI. This light-hearted performance has two parts. The first consists of music, chanting, and dancing, with the audience participating. The second part is a series of short plays and skits made up by performers. These comic presentations make fun of character types such as the blind man, the miser, the leper, and others. The official theater company of Mali, the National Koteba, works to preserve the techniques of traditional performance.

The Colonial Era

During the colonial era European authorities discouraged or even banned some forms of traditional theater. Most colonists had little respect for non-Western culture. In addition, Europeans believed that most traditional theater was linked to African religious practices, which they wanted to eliminate and replace with Christianity.

Europeans introduced new styles of theater, as well as new subject matter, to Africa. Missionaries taught elements of Christianity by having people act out scenes from the Bible. Students performed short plays in school. Europeans in major colonial cities established theater companies that presented white audiences with familiar plays in European-style settings. In EGYPT in the late 1800s, a movement to translate European literature into Arabic led to Arabic versions of French plays. They were performed with Egyptian slang and settings to make them more understandable to local audiences.

Colonial administrators also used theater as a means of communicating with and educating Africans. In the 1930s in Nyasaland (now MALAWI), plays were staged for African audiences to promote health care. In the 1950s a play called The False Friend encouraged farmers to adopt new agricultural techniques.

Despite colonial domination, Africans continued to perform traditional theater whenever possible, and their performances reflected the changes that were taking place in African life. During rituals of spirit possession in southern MOZAMBIQUE, performers began to impersonate foreigners. Elsewhere, Africans created dances, masks, and songs that imitated and also mocked the culture of the white colonists. Traditional theater sometimes took on political significance, such as in KENYA, where Africans performed indigenous rituals during the MAU MAU rebellion against colonial authorities.

As young Africans studied Western literature in colonial schools, some of them began writing new plays in the Western style, using both African and European languages and themes. The Egyptian dramatist Tawfiq al-Hakim wrote plays based on legends and myths from both European and Arabic culture. In southern Africa, Herbert Dhlomo wrote a play in English about a Xhosa legend.

Modern Theater

By the 1930s modern African theater was emerging, with new styles and wider recognition. Egypt became a major theatrical center not just of North Africa but of the entire Arab Middle East. Visits by Egyptian theater companies inspired the growth of theater in MOROCCO and TUNISIA. Throughout Africa, playwrights began experimenting with new subject matter.

For many African playwrights, theater offered a way to express views on important issues and perhaps even to bring about social or political change. Beginning in the late 1950s, South African playwrights such as Athol FUGARD wrote about people living in the shadow of apartheid. In the 1970s the Black Consciousness movement in South Africa argued that before Africans could achieve political freedom, they must liberate their traditional culture from the restrictions imposed by white authorities. Theater groups such as the Peoples' Experimental Theatre stood trial under South Africa's Terrorism Act for presenting plays that the government considered dangerous or possibly revolutionary.

As other African nations were freed from colonial rule in the 1960s, independence brought new energy to theater. Many writers rejected colonial influences and began to use traditional elements in creative ways. West African playwright Ola Rotimi wrote in English but added African PROVERBS and expressions to his plays. Focusing on episodes from African history, his works included Kurunmi (1969), a play about wars among the YORUBA people.

While some playwrights explored the effects of colonialism on Africa, others emphasized African social problems. In her play The Dilemma of a Ghost (1964), Ghanaian writer Ama Ata Aidoo addresses the subject of conflicting cultures by showing the turmoil in a village when a young man introduces his African-American wife. Marriage and family relationships form the material of many plays with social messages. Daudo Kano and Adamu dan Gogo of Nigeria criticized the practice of polygamy in Tabarmar Kunya (A Matter of Shame, 1969).

Important modern playwrights have come from all parts of Africa. Many of these artists continue to play a role in changing the social and political directions of their countries. Izz al-Din of Morocco is known for his works on the subject of revolution. In his play Thawrat Sahib al-Himar (The Donkey-Owner's Revolt, 1971), the heroine confronts her male-dominated society and questions its practices. Nigerian writer Wole SOYINKA, the first African to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, has written plays criticizing aspects of modern Nigerian society and politics.

Kabwe Kasoma of ZAMBIA and Tse-gaye Gabre-Medhim of ETHIOPIA have attempted to shape the development of their countries by writing plays that expose the truth behind historical events and cultural tensions. In some African nations, such playwrights—like other writers—have been jailed, exiled, or even killed for expressing their views. Kenyan playwright Ngugi wa THIONG'O was arrested for criticizing the government in his plays, and he eventually left Kenya so that he could work safely.

In recent decades, African theater has been expanding both within the continent and worldwide. Many African nations, including BENIN and IVORY COAST, host local theater festivals, and an international association of performers is based in CONGO (BRAZZAVILLE). The International Theater for Development Festival, held every two years in Ouagadougou, BURKINA FASO, promotes theater that is used to encourage social change or to debate important issues in African life. Some African plays and musicals, such as Sarafina! (1990) have become popular hits in the United States and other countries, and many African performing groups now bring African theater of all varieties to audiences around the world. (See also Dance, Masks and Masquerades, Music and Song, Oral Tradition.)