Education

In the modern world no country can hope to prosper and advance without an educated population. During most of the colonial period, Africa's black population was systematically denied access to quality schooling and higher education. After gaining independence, most African states made it a priority to strengthen their educational systems. That process has not always been smooth, and serious problems remain. However, many African nations made major strides in education over the past 50 years.

COLONIAL EDUCATION

During the early colonial period, European powers had little interest in educating the indigenous populations of their African colonies. They were concerned with extracting the continent's natural wealth, not with building functioning nations. Nor did they envision Africans as playing a significant role in the colonial government or economy. As a result, there were few schools of any kind for local populations before the mid-1800s.

Religious Roots

Without government support, education in Africa was left in the hands of missionaries and other religious groups. Islamic schools had existed in North Africa for hundreds of years. They were generally small and limited to those who practiced the Muslim faith. European missionaries established schools in the coastal areas of West Africa in the 1600s and 1700s, but these early schools lasted only a short time.

When Christian missionaries began arriving in Africa in greater numbers in the early 1800s, they made a serious effort to educate local populations. The goal of the early missionary schools was to produce literate individuals to take over minor positions in local churches and become functioning church members. However, missionary schools served a limited number of Africans because they were usually located in coastal towns or near mission stations. They also suffered from lack of money and staff. As long as education remained in the hands of religious groups—either Islamic or Christian—it would reach only a small number of Africans and be restricted to certain subjects.

Government and Education

As Europe's African colonies grew larger and more prosperous, colonial rulers began to see the need for general education. On the one hand, more and more Europeans were working and settling in Africa, and these settlers demanded schools for their children. On the other hand, European officials realized that prosperity depended on having a trained local workforce that could handle tasks in the colony's political and economic organizations. Providing basic instruction in reading and writing and some technical training gained new importance. The need for a more educated population led to the establishment of government-sponsored schools throughout Africa.

The schooling offered by the various colonial powers had similar features. The vast majority of schools were primary schools, with a limited number of secondary schools and almost no colleges or universities. A school's curriculum often depended on its location. Students in rural schools usually learned skills needed to work in agriculture, while children in urban areas received training to work in crafts or as laborers in industry. The secondary schooling available to Africans was aimed primarily at training teachers or preparing individuals for lower-level professional jobs such as nurses, railroad engineers, or clerical workers. A few of the most gifted students might be trained for minor positions in local government. In general, European administrators viewed education as a way to make Africans more useful to the colonial system, not to offer them opportunities for advancement.

Schooling and Segregation

In most African colonies, whites and blacks attended separate schools with separate goals. “White” schools generally were part of a well-funded educational system consisting of primary, secondary, and tertiary (college and university) institutions based in Europe. Students who graduated from one level advanced to the next and were often evaluated to determine an appropriate career path.

Colonial schools for blacks were designed to train an African workforce. Usually poorly funded and understaffed, the schools were not tied into any larger system that would allow the best students to move on to higher education. Colonial officials occasionally allowed bright African students to attend “white” schools, but this was a rare occurrence that required special arrangements.

The most racially segregated educational system developed in SOUTH AFRICA. In the early 1900s, the country had a racially segregated educational system. Yet small numbers of the black students who graduated from the best missionary schools were able to receive a decent secondary education. Then, in 1948, the strongly racist National Party gained control of the South African government, introduced apartheid, and began making significant changes in the country's educational system.

The National Party adopted a policy known as Christian National Education (CNE), which declared that whites and other ethnic groups should each have their “own education” suited to their “own needs.” The Bantu Education Act of 1953, based on this policy, gave the national government responsibility for educating nonwhites and led to the elimination of most missionary schools. The South African government provided ample funding and resources for white schools but very little for nonwhite ones. The result was a highly fragmented, second-class educational system for blacks. Missionaries and certain other groups criticized these policies, but almost nothing was done to change the educational system until the end of apartheid in the early 1990s.

Higher Education in the Colonial Era

For centuries the only formal institutions of higher education in Africa were Islamic schools such as the University of Timbuktu (in present-day Mali) and the famous al-Azhar University in Cairo, Egypt. Established in A.D. 970, al-Azhar is the oldest continuously operating university in the world.

Like most traditional Muslim schools, these institutions had no formal program of study and awarded no degrees. Their primary goal was to develop strong devotion to the teachings of Islam and produce religious leaders and judges trained in Islamic law. In the late 1800s, the Egyptian government took steps to modernize the curriculum of al-Azhar and to transform it into a true university. It has since developed into one of the foremost universities in the Muslim world.

The first western-style institution of higher education in Africa was Fourah Bay College, founded in 1827 in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Established by the Church Missionary Society, the school was intended to train religious leaders for the Anglican Church. Other early colleges in western Africa, such as Liberia College in Monrovia, Liberia, were also centers of religious training.

Two years after Fourah Bay College opened, the South African College was established in Cape Town. Other colleges followed, including the South African Native College, founded in 1916 to educate blacks. Although black students could attend white colleges at this time, few did so. All these early colleges were in British colonies. The French and other colonial powers did not establish colleges or universities in Africa until the 1950s.

POSTCOLONIAL EDUCATION

The neglect and discrimination that marked education during the colonial period has had harmful effects on education in Africa since independence. When the colonial powers withdrew during the 1960s, they left behind a largely uneducated black population. Since that time, African leaders have faced the enormous task of producing enough highly trained individuals to run their countries while providing basic education for the majority of their citizens.

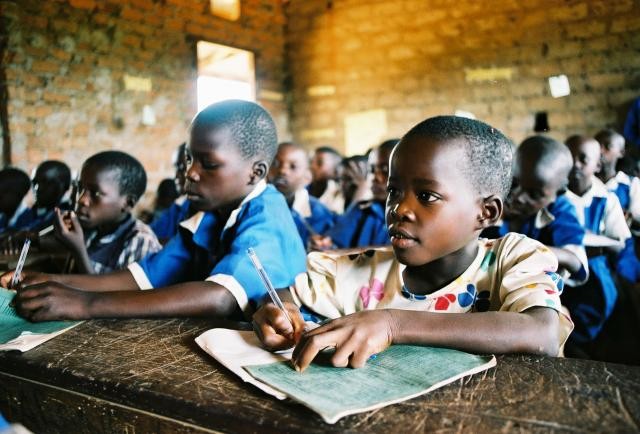

Primary and Secondary Education

One of the main educational goals of most African nations since independence has been to provide an education for all citizens. Many countries have come close to achieving this goal at the primary level. In the Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Cameroon, Gabon, Tunisia, Algeria, and Nigeria, around 90 percent or more of all children of primary-school age attend school. In many other countries, however, particularly those torn by civil war such as Chad and Angola, the numbers of students attending primary school are much lower.

In general, primary school attendance drops significantly in rural areas, and the number of girls in school is generally lower than the number of boys. In most African countries primary education is required of all children until they reach a certain age. In many places, however, only about half of the students who attend primary school finish the entire course of study, and in some areas more than 90 percent of primary school students repeat at least one grade.

A much smaller percentage of students attend secondary school than primary school. Nevertheless, the number of students in secondary schools today is dramatically higher than during the colonial period. Moreover, secondary education is increasingly available in many rural areas.

After independence, school enrollment throughout Africa skyrocketed, and few African nations have been able to find adequate funds for their educational systems. Although in many places primary and secondary education is officially free of charge, most nations do not have the resources to provide educational materials and equipment. Parents are often required to purchase textbooks, and local communities are typically responsible for constructing classrooms or school buildings. Many schools are overcrowded and have a shortage of qualified teachers.

During the colonial period, most of the people trained to run the government and economy were Europeans. They left after independence. Faced with the need to quickly train people to fill positions of leadership, most African countries gave more financial support to colleges, universities, and technical schools than to basic education. They could not hope to survive in the modern world without a core of educated professionals, technicians, and civil servants. Focusing on higher education did produce people capable of running government agencies and business enterprises, but it drained much-needed resources from primary and secondary schools.

One of the main problems facing African school systems today is that there are too few jobs available for the students who finish school. For most of the postindependence period, a large portion of secondary school graduates found positions in government. In recent years, however, financial problems have forced most nations to drastically reduce the size of government and the number of jobs. Another problem is that African schools do not seem to be teaching the kinds of skills needed by most private companies. The schools also face the challenge of linking education with the needs of local communities. Instead of applying the knowledge and skills they learn at school in their local communities, many students leave their towns or villages for jobs in the cities or even other countries.

Higher Education

The number of colleges and universities in Africa has grown dramatically since independence. This is especially true in former British colonies. In Nigeria, the government founded seven new universities in the mid-1970s alone. East Africa also saw the establishment of many new schools of higher learning in the 1970s and 1980s. In some countries, such as Kenya, Tanzania, and Ethiopia, the state pays the full cost of a university education. However, budget problems have forced some colleges to ask students to share part of the cost of their education.

South Africa has a well-developed system of higher education, featuring 21 universities, about 100 colleges, and 15 technical schools, with a total enrollment of more than half a million students. The legacy of apartheid, however, has left former “white only” schools with significant advantages over former “tribal colleges,” often referred to as “historically black universities.” Nevertheless, a number of South African colleges and universities now offer high-quality instruction. In 1994, the South African government created the National Commission on Higher Education to oversee the development of colleges and universities. Some of the key issues the commission addressed included funding for higher education, the transformation of institutions after the end of apartheid, and providing access to higher education for students that had suffered discrimination under apartheid.

Perhaps the main issue facing South Africans as they struggled with education after apartheid was balancing the government's limited resources with the need to maintain a high-quality system of higher education. People throughout Africa view colleges and universities as important tools of national development that will enable their nations to grow and prosper. The desire to compete in the modern world has led to the establishment of new and separate universities specializing in science and technology. These institutions have been successful in attracting students and filling staff positions with Africans. However, men and women do not have the same opportunities in higher education. Most African colleges and universities have few female faculty members, and male students far outnumber females in most institutions.

Educational Alternatives

Dissatisfaction with the quality of public schools at all levels has led a growing number of Africans to seek alternative forms of education. Some can afford to send their children to private schools. Many university and college students study abroad, usually in Europe or the United States.

Muslim parents who want their children to get a more religiously based education may send them to Islamic schools. Usually attached to a mosque, these schools offer instruction in the Qur'an, the holy book of Islam. Students who advance beyond the elementary level learn to read and write Arabic and study Islamic texts in greater depth. The madrasa, a more modern form of Islamic schooling, features both religious instruction and Western-style education. A number of Islamic colleges and universities, mostly in the Arabic countries of North Africa, also exist to serve Muslim Africans. (See also Colonialism in Africa; Childhood and Adolescence; Development, Economic and Social; Islam in Africa; Missions and Missionaries; Oral Tradition; Women in Africa.)