Mau Mau

Mau Mau began as a movement by Africans against British rule in KENYA in the 1950s. Eventually the movement became a guerrilla war. With complex political, economic, and social roots, Mau Mau has been interpreted in various ways. To the fighters and their supporters, Mau Mau was a struggle for liberation. To European settlers and British officials, it was an outbreak of terrorism and primitive violence. Although the British ended the rebellion with military force, Mau Mau forced them to change their role in Kenya and opened the way for majority rule by black Africans in 1963.

Origins of Mau Mau. The origin of the term Mau Mau is unknown, but it had come into use by 1947. The British colonial administration in Kenya soon associated it with an underground antigovernment movement. This movement arose at the end of a long period during which Africans had tried without success to change the policies of land ownership, government, and social organization that made them secondclass citizens in their own country.

Many of the Africans' grievances concerned land. In the early 1900s, the British began establishing white settlers in Kenya. They created an economy based on export crops such as coffee. More than 7.5 million acres of land once inhabited by the MAASAI, GIKUYU, and other peoples were set aside for about 4,000 European-owned plantations and farms. The desire to reclaim these “stolen lands” became a powerful force in Mau Mau.

Before the late 1930s, Africans were not allowed to grow coffee and other high-income crops. In order to raise money to pay for taxes, schooling, and medical care, many black men became migrant workers on white-owned farms, docks, and railways. African laborers received low wages, and those who worked in cities lived in poor housing. The result was a tension-filled society divided by race into unequal classes.

Although Africans were not represented in the Kenyan legislature, they organized a number of political and social welfare associations to promote their goals. The Gikuyu people founded the Kikuyu Central Organization (KCA) in 1924. At the outbreak of World War II in 1939, colonial authorities banned the KCA, fearing it might form an alliance with Germany, Britain's enemy. The KCA went underground, becoming secretive and militant. Other African groups did the same, even after the war ended in 1945. Trade unions of African laborers called many strikes in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The sense of militancy and unrest felt by many Kenyans, especially young people, was channeled into Mau Mau.

Activities and Effects. Mau Mau began with threats and acts of violence among the Gikuyu, both in rural areas and in urban centers such as NAIROBI. The government banned Mau Mau in 1950, but the violence continued, directed against both Europeans and Africans who were believed to be opposed to the movement.

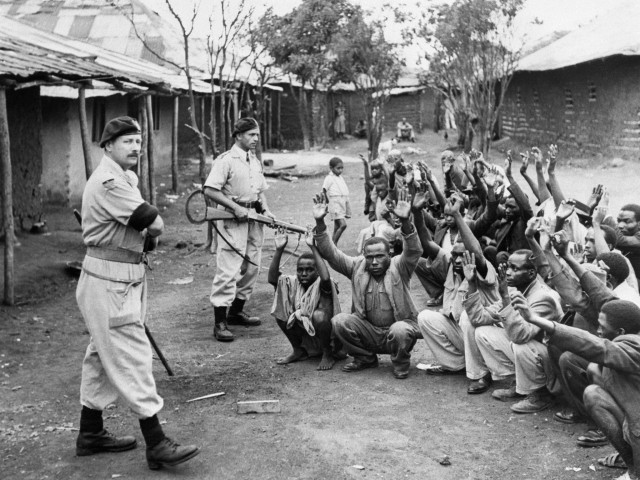

A key element in establishing Mau Mau was the use of secret militarystyle oaths to bind members in a pact against the colonial government. The nature of these oaths made it clear that Mau Mau leaders expected a military confrontation with the government. In 1952 Mau Mau fighters assassinated an African chief who supported the British. The government responded by declaring a state of emergency and arresting more than 150 black political and labor leaders. Authorities also questioned and imprisoned thousands of Africans, mostly Gikuyu.

The Kenyan fighters rejected the label “Mau Mau” and used other names, such as the KCA or the “Kenya Land and Freedom Army,” to refer to themselves. Among them were peasants, urban workers, the unemployed, and World War II veterans, as well as a few educated individuals and some women. The lifeline of their movement consisted of the men, women, and children who did not actually belong to Mau Mau but provided food, medical supplies, ammunition, and information. Not all Africans aided or approved of the movement, however, and Mau Mau support varied from region to region.

The British viewed Mau Mau as something from Africa's past, and they regarded the group's often violent practices as a sign of breakdown among Africans. Yet the authorities used equally brutal methods to crush the movement. By 1956 British forces had defeated Mau Mau. The war left at least 12,000 Africans and about 100 Europeans dead. It also changed the social and political landscape of Kenya forever. Although the Mau Mau leaders had not provided a clear plan for the future, most who supported the movement sought return of the “stolen lands” and political independence for Kenya. The British had put down the rebellion but could not ignore its message. Mau Mau shocked Britain into beginning the reforms that led to black majority rule and to the return of land to Africans. (See also Colonialism in Africa, Independence Movements.)