Democratic Republic of the Congo

POPULATION: 69.36 million (2014)

AREA: 905,560 sq. mi. (2,345,410 sq. km.)

LANGUAGES: French (official); Kongo, Lingala, Swahili, Tshiluba, Ngwana

NATIONAL CURRENCY: Congolese franc

PRINCIPAL RELIGIONS: Christian 80% (Roman Catholic 50%, Protestant 20%, Kimbanguist 10%), Muslim 10%, Traditional 10%

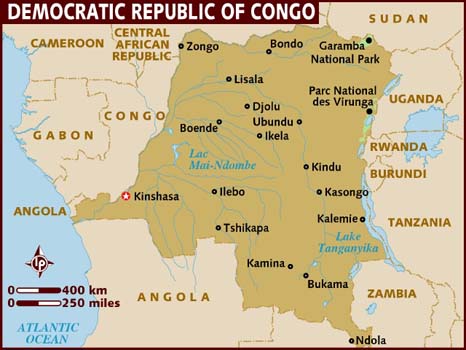

CITIES: Kinshasa (capital), 5,064,000 (2000 est.); Kisangani, Lumbumbashi, Kanaga, Likasi, Mbandaka, Mbuji-Mayi, Bukavu

ANNUAL RAINFALL: Varies from 30–60 in. (800–1500 mm) in south to 80–118 in. (2,000–3,000 mm) in central basin rainforest

ECONOMY: GDP $32.96 billion (2014)

PRINCIPAL PRODUCTS AND EXPORTS:

- Agricultural: coffee, sugar, palm oil, rubber, tea, cassava, bananas, corn, fruits

- Manufacturing: mineral processing, cement, textiles, leather goods, cigarettes, processed food and beverages

- Mining: diamonds, cobalt, copper, cadmium, gold, silver, zinc, iron ore, coal

GOVERNMENT: Independence from Belgium, 1960. Dictatorship.

HEADS OF STATE SINCE INDEPENDENCE:

- 1960 Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba

- 1960–1965 President Joseph Kasavubu

- 1965–1997 President Mobutu Sese Seko

- 1997–2001 Laurent Desire Kabila

- 2001– Joseph Kabila

ARMED FORCES: 50,000 (2000 est.)

EDUCATION: Compulsory for ages 6–12; literacy rate 77%

The Democratic Republic of Congo—formerly known as Zaire—is the second-largest country in Africa. Located in the center of the sub-Saharan region, the Congo is huge and diverse and blessed with abundant natural resources. But the nation's history is troubled. Since gaining independence in 1960, it has been plagued by violence, dictatorial rule, economic mismanagement, and political corruption. Once a land of promise, the Congo has become the prime example of the problems facing modern Africa.

GEOGRAPHY

The Democratic Republic of Congo is about the size of the United States east of the Mississippi River. Except for a very small section of coastline along the Atlantic Ocean, the country is landlocked.

The Congo is dominated by the CONGO RIVER, one of the largest rivers in the world. The river divides the country into four distinct geographic regions. In the center of the country is the immense Congo Basin, or Central Basin, an area of roughly 300,000 square miles covered by dense tropical rain forest. This hot, humid region contains a number of large plantations that produce coffee, cocoa, palm oil, and rubber. It is the most thinly populated area of the country.

North and south of the rain forest are woodlands. These areas, which enjoy abundant rainfall, a fairly temperate climate, and two growing seasons per year, produce most of the country's food. The majority of the nation's inhabitants live in the woodland areas.

The easternmost part of the Congo features high mountains rising to nearly 17,000 feet. With rich volcanic soils, this fertile region produces a variety of food crops as well as coffee and tea. The southernmost part of the Congo consists of forested savanna and has a much drier climate and relatively few inhabitants.

HISTORY AND GOVERNMENT

The history of the Democratic Republic of Congo has been marked by violence and exploitation of the people by their leaders. This pattern, established under Belgian colonial rule from 1885 to 1960, continued after independence under MOBUTU SESE SEKO.

Precolonial and Colonial History

The first large state to emerge in the region was the kingdom of Kongo, which by 1500 covered an area of about 30,000 square miles. Kongo dominated the region until 1665, when civil war broke out after the death of the king. The Portuguese, who had been active in the area since the late 1400s, tried to take advantage of the confused situation by invading Kongo. Kongolese forces defeated the Portuguese, but the continuing war and internal rivalries greatly damaged the kingdom. It never regained its former power.

In the late 1800s, the Belgian king Leopold II sent American adventurer Henry Morton STANLEY to explore the Congo River basin. Although Stanley had already traveled parts of the region, he had never journeyed so far inland. On his mission for Leopold, Stanley signed several treaties with local chiefs. Leopold then used the treaties to lay personal claim to the area. In 1885 an international agreement in Europe gave the king ownership of the region, then known as the Congo Free State. Leopold leased parts of his territory to private companies that wanted to profit from the region's riches. The companies used brutal tactics to force the local population to work for them on rubber plantations, in the mines, as porters, and to serve in the colonial army. Some scholars estimate that violence, overwork, and starvation killed perhaps as many as 10 million Congolese people in 20 years.

Leopold ran the Congo Free State as his own private kingdom until 1908, when in disgust at his greed, the Belgian government declared it a colony of Belgium. Many of Leopold's practices continued under Belgian rule, although treatment of the indigenous population was slightly less brutal. Virtually all state resources and services were controlled by colonial authorities and foreign companies, and the local people had little or no say in economic or political matters.

Independence and the Congo Crisis

By the 1950s the independence movements sweeping through Africa spread to the Belgian Congo. In response to Congolese demands for greater rights, the Belgian government proposed a 30-year timetable for independence. Most Congolese found this unacceptable, and mounting political and economic unrest in the late 1950s forced the Belgians to grant the Congo independence in 1960.

The first president of the new nation was Joseph Kasavubu; Patrice LUMUMBA, a political rival, served as prime minister. Within weeks of independence, the Congolese army mutinied and civil unrest spread throughout the country. Hundreds of Europeans were massacred and thousands fled the country and returned to Europe. As the revolt continued, Prime Minister Lumumba asked the UNITED NATIONS (UN) to send troops to restore order. Lumumba also sought assistance from the Soviet Union, and soon the United States became involved in the conflict as well, raising the prospect of a major war. During this time, the important copper mining region of Shaba in the southeast declared its independence from the new nation.

The Congolese military soon stepped in to help Kasavubu, aided by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. The military arrested Lumumba and turned him over to the leader of the Shaba rebels, Moise TSHOMBE, who had Lumumba killed. Meanwhile, civil war continued to rage between Shaba and the Congo. In 1962 the UN proposed a peace plan, but Tshombe resisted it, believing he could conquer the entire country. But the forces against him were too powerful, and he surrendered to Kasavubu the following year. In 1965 Kasavubu was himself overthrown by Colonel Joseph Desire Mobutu, who would rule for more than 30 years with the help of U.S. financial support.

The Mobutu Years

Mobutu immediately moved to consolidate power in his own hands by eliminating political opponents and stirring up rivalries between competing ethnic groups. He also dissolved the parliament and created a single party to control political life. In 1971 Mobutu changed the country's name from Congo to Zaire, which he claimed was an African word for “big river” (it was actually a Portuguese mispronunciation of the word for river.) He also took the name Mobutu Sese Seko (“the all-powerful”) and declared European names illegal. He even went so far as to outlaw neckties because they were part of Western clothing.

Instead of building up the country, Mobutu and his allies robbed it. Mobutu took possession of foreign-owned businesses and gave them to his friends and supporters, who proceeded to destroy much of the nation's economy. In addition, political corruption became widespread because poorly paid public officials had to accept bribes to make a living. In the mid-1970s Mobutu issued some reforms in an attempt to ease some of the economic conditions his policies had created. The reforms had little effect.

Mobutu's dictatorship allowed no opposition, and many of his policies were very harsh. Yet Mobutu received support in the 1970s and 1980s from the United States and other Western countries because of his opposition to communism. During this period, Zaire's southern neighbor ANGOLA was in the midst of its own civil war, and Western nations saw Mobutu as a stronghold against the Communist forces battling in Angola. By the 1980s Mobutu faced increasing criticism at home and abroad. Zaire's economy was in a disastrous state, public servants were unpaid and restless, and public order was disintegrating. When the Cold War ended in the early 1990s, Mobutu's Western allies no longer needed him as a stronghold against communism.

As Mobutu saw his control of events slipping away, he made a desperate bid to stay in power by approving multiparty elections in 1990. However, he kept postponing them for various reasons. The next year the economy almost totally collapsed, and riots and violence swept through Zaire, killing hundreds of people and destroying much of the nation's infrastructure.

In 1996 rebel forces in eastern Zaire, led by Laurent Kabila, began marching west toward the capital of KINSHASA. Zaire's armed forces were so disorganized and demoralized that they offered almost no resistance. In less than a year, the rebels gained control of the entire country and forced Mobutu from power.

The Congo Today

When Kabila took over as president in 1997, he changed the country's name to The Democratic Republic of Congo and promised that elections would be held after a two-year period of reorganization. However, Kabila made little progress in introducing democracy, and his government proved to be almost as corrupt and brutal as the one it replaced.

By mid-1998 Kabila himself faced a rebellion after ousting the military advisers who had helped him to power. These advisers led a rebel force that nearly captured Kinshasa before Kabila called for support from neighboring Angola and ZIMBABWE. Within months the conflict expanded to include CHAD, ANGOLA, LIBYA, RWANDA, UGANDA, and even Zimbabwe. By the year 2000, rebel forces controlled the eastern third of the Congo, while Kabila ruled the rest of the country with the military support of his foreign allies. Like Mobutu before him, Kabila ruled by force and by decree, but his hold over the country was largely dependent on the continued presence of foreign forces. In January 2001, Kabila was assassinated and his son, Joseph, was sworn in as president.

ECONOMY

About 75 percent of the people of the Democratic Republic of Congo are engaged in agriculture. Most farms are small, lack modern equipment, and use little in the way of improved seeds or fertilizer. Although some plantations employ more modern, large-scale farming methods, this type of agricultural production has decreased over the past 30 years. Mining has been an important part of the nation's economy since the colonial era. Copper was the main export until the early 1990s, when it was replaced by diamonds. Manufacturing is concentrated in the capital city, Kinshasa, and in a few other urban centers. However, manufacturing represents only a small percentage of the nation's economic activity.

In the early 1970s, high copper prices and political stability led to several years of growth in the country's economy. Then in 1973, the nation's president, Mobutu Sese Seko, seized all foreign-owned businesses and gave them to Zairians who supported his regime—a policy known as Zairianization. Most of these new owners had little business experience and no particular interest in making their companies profitable. Instead, they enriched themselves on whatever profits they could make.

Zairianization had a disastrous effect on the nation's economy. Many businesses went bankrupt because of poor management and corruption, and the economy began a long-term decline. Industrial production and mining decreased dramatically. High rates of inflation made the nation's currency virtually worthless. With no money to spend on maintaining roads and other transportation services, the country saw its infrastructure deteriorate. As a result, the cost of moving food from the countryside to the cities rose sharply and food prices skyrocketed.

In the 1990s, the economic problems led to rioting, looting, and general civil disorder. Civil war erupted in the mid-1990s. Today, the nation's economy remains in desperate shape and shows little sign of improving in the near future, despite the nation's natural riches and potential.

PEOPLES AND CULTURES

The population of the Congo is unevenly distributed. Most of the people are concentrated in a few areas, more than half of them in cities. About 70 percent are Christian, including many members of the Kimbanguist Church—a Baptist-style church founded in Congo by Simon KIMBANGU. Between 20 and 25 percent practice traditional African religions. The remaining 5 to 10 percent of the Congolese people are Muslim. Many of the Christians include elements of traditional religions in their rituals and beliefs.

The Congo is home to about 300 different ethnic groups of varying sizes. The most important factor in determining a person's ethnic identity is LANGUAGE. The country has more than 200 languages, but four BANTU languages stand out above the others. Used for instruction in most schools, these four languages—Lingala, SWAHILI, Tshiluba, and Kongo—also dominate radio and television broadcasting.

Shared histories and participation in the economy and government play a role in ethnic identity in the Congo today. In practice, ethnicity is very flexible, and people often identify themselves with more than one group. A single national culture does not yet exist, although a common national identity is only now beginning to take shape in the nation's cities, especially Kinshasa. (See also Colonialism in Africa, Global Politics and Africa.)