Republic of Sierra Leone

POPULATION: 6.316 million (2014)

AREA: 27,699 sq. mi. (71,740 sq. km)

LANGUAGES: English (official); Krio, Temne, Mende, Limba

NATIONAL CURRENCY: Leone

PRINCIPAL RELIGIONS: Muslim 60%, Traditional 30%, Christian 10%

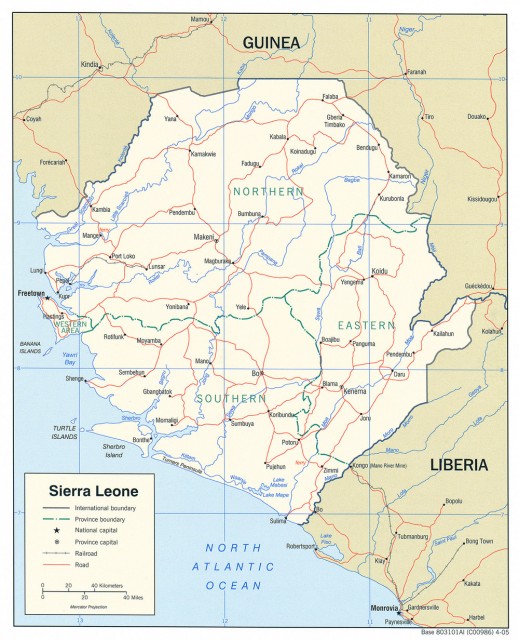

CITIES: Freetown (capital), 669,000 (1990 est.); Bo, Koindu, Kenema, Makeni

ANNUAL RAINFALL: Varies from 200 in. (5,000 mm) on the coast to 85 in. (2,160 mm) in the north.

ECONOMY: GDP $4.838 billion (2014)

PRINCIPAL PRODUCTS AND EXPORTS:

- Agricultural: coffee, cocoa, palm kernels, rice, palm oil, peanuts, livestock, fish

- Manufacturing: mining, beverages, textiles, cigarettes, footwear, petroleum refining

- Mining: diamonds

GOVERNMENT: Independence from Britain, 1961. Republic with president elected by universal suffrage. Governing bodies: 80-seat House of Representatives (legislative body), with 68 members elected by popular vote; Ministers of State, appointed by the president.

HEADS OF STATE SINCE INDEPENDENCE:

- 1961–1964 Prime Minister Sir Milton Margai

- 1964–1967 Prime Minister Sir Albert M. Margai

- 1967 Brigadier David Lansana

- 1967–1968 Brigadier Andrew T. Juxon-Smith

- 1968–1986 Prime Minister Siaka Stevens (president after 1971)

- 1986–1992 President Joseph Saidu Momoh

- 1992–1996 Captain Valentine Strasser

- 1996 Bridadier Julius Maada Bio

- 1996–1997 President Ahmed Tejan Kabbah

- 1997–1998 Major Johnny Paul Koroma

- 1998– President Ahmed Tejan Kabbah

ARMED FORCES: 5,000 (2001 est.)

EDUCATION: no universal and compulsory education system exists; literacy rate 31% (2001 est.)

Established as a haven for former slaves, Sierra Leone was for many years one of Africa's success stories. When it gained independence in 1961, this resource-rich nation had a prosperous merchant class and a long history of representative government. Its recent history, however, has been filled with political instability and violence. Since 1991 a devastating civil war has reduced the nation to a state of chaos.

GEOGRAPHY

Sierra Leone is located on the Atlantic coast of West Africa between the countries of GUINEA and LIBERIA. Its broad coastal belt, covered by dense mangrove swamps, gives way to wooded hills and gently rolling plateaus in the interior. The mountainous southeastern portion of the country features peaks up to 6,000 feet high. The climate of Sierra Leone is extremely hot and humid, with average rainfall of about 200 inches along the coast. Dense tropical rain forest covers portions of the country's land area.

HISTORY AND GOVERNMENT

Europeans first visited Sierra Leone in 1460 when Portuguese explorer Pedro de Cintra landed on the coast. He named the area Sierra Leone, meaning “Lion Mountains,” because of the beauty of its mountains. At that time the region was thinly settled by indigenous Mende and Temne people. Contact between local peoples and coastal traders was frequent throughout the period before European rule.

Refuge for Slaves

In 1787 a British abolitionist named Granville Sharp persuaded his government to establish a colony in Sierra Leone for people of African descent living in Britain. The first settlers to arrive angered a local Temne chief and were driven away. Four years later a private London firm called the Sierra Leone Company reestablished the settlement. The company hoped to introduce “civilization” and replace the local trade in slaves with trade in vegetables grown in the region.

The Sierra Leone Company recruited about 1,200 colonists from Canada, who founded the coastal settlement of FREETOWN in 1792. The group included American blacks, loyal to Britain, who had been freed during the American Revolutionary War. The Sierra Leone Company and its colonists disagreed about the purpose of the colony. The settlers viewed Sierra Leone as a haven of freedom in which to start a new life; the company regarded it as a moneymaking venture. These disputes led to an armed uprising of settlers in 1800 that was put down by the company.

Growing Pains

The Sierra Leone Company had problems not only with settlers but also with local Temne rulers. In the past the Temne had leased land to European slave traders but had kept control over it. However, in the treaties they signed with the Sierra Leone Company the Temne unknowingly surrendered control of the land to the company. This led to arguments that resulted in war. In 1801 and 1802 Temne forces attacked Freetown, but the British eventually drove the Temne away from the area.

The Temne were not the only threat to the colony. Britain and France went to war in 1793, and the following year French forces burned Freetown to the ground. Because of continuing losses, the Sierra Leone company could not make a profit, and in 1808 it yielded control of the colony to the British Crown. In the following years, Sierra Leone became a naval base from which the British conducted raids on ships that violated Britain's ban on the SLAVE TRADE. Enslaved Africans who were picked up on the ships were resettled in Freetown.

Sierra Leone Flourishes

During the early 1800s, some 80,000 freed slaves were settled in Sierra Leone. Under the guidance of missionaries and British officials, most converted to Christianity, learned English, and adopted Western names and lifestyles. The mixing of people from different backgrounds and races produced a Creole society that combined elements of both African and European culture. In time the members of this mixed population became known as Krio.

With little European competition, Krio traders in Sierra Leone established profitable import-export businesses dealing in timber, palm oil, and palm kernels. A Krio middle class emerged that invested in land and built large houses for themselves. Prosperous Krio business leaders contributed generously to the building of churches and schools. Christian missions provided schooling for children, and in 1827 the Church Missionary Society founded Fourah Bay College for higher education. With these educational opportunities, new generations of Krio became doctors, lawyers, and government officials.

The majority of the Krio population were originally YORUBA people from NIGERIA who kept many of their cultural traditions, such as belief in Islam and membership in SECRET SOCIETIES. Over time, many people from surrounding areas moved to Freetown. Although the Krio worked alongside these newcomers, they tended to separate themselves from non-Krio groups. Some Krio even considered them a threat.

By the 1840s lack of employment opportunities forced many Krio to leave Sierra Leone. Some returned to their Yoruba homeland, while others decided to start new businesses elsewhere. This migration took many educated Krio to neighboring colonies such as the Gold Coast (presentday GHANA), the GAMBIA, Nigeria, and Liberia, where they became missionaries, traders, businesspeople, and government workers. The stream of emigrants from Sierra Leone formed the nucleus of an African middle class in British West Africa during the late 1800s.

The Road to Independence

During the 1800s tensions arose and intensified between the Krio and local British businessmen. To protect their commercial interests against Krio competition, Britain annexed the interior of Sierra Leone in 1896 and established a protectorate. Two years later the British imposed a Hut Tax on Africans to help pay the cost of colonial government. This led to an armed uprising in 1898, and resistance to British rule increased over the following years.

At about this same time, the British began expanding the political rights of Sierra Leoneans. In 1882 the colonial council appointed its first black member, and regular elections were held in Freetown beginning in 1895. Outside Freetown, however, few people had the right to vote. Furthermore, despite Sierra Leone's history as a haven for former slaves, its first antislavery law was not passed until 1926. By this time tensions existed not only between the Krio and the British but also between the Krio and the colony's growing Lebanese population. Social tensions sometimes erupted in protests, violent riots, and forms of guerrilla warfare.

By the 1950s events were rapidly moving toward independence for Sierra Leone. A constitution adopted in 1951 called for a black majority in the Legislative Council, and within six years all residents in Sierra Leone had the right to vote. By the time independence came in 1961, Sierra Leone had a long history of participatory government marked by free and fair elections.

Civilian Rule

The country's first prime minister, Sir Milton Margai, ensured that Sierra Leone enjoyed a free press, open debate in government, and effective participation in the political process by people throughout the land. When he died in 1964, his half-brother Albert was elected prime minister. However, the second Margai lost support when he tried to set up a one-party state. In the 1967 elections the ruling Sierra Leone People's Party (SLPP) was defeated by the opposition party, the All People's Congress (APC). Shortly after the APC candidate Siaka Stevens became the new prime minister, the military staged a coup. But military rule met with considerable opposition, and Stevens was returned to power a year later.

Stevens and the APC took the coup as a warning against weakness and quickly moved to establish stronger control over the government. Political corruption and violence increased, and by 1978 Sierra Leone had become a single-party state under APC leadership. Although Stevens was popular at first, growing corruption combined with a declining economy undermined his support. Faced with political defeat, Stevens resigned in 1986 and turned the government over to a handpicked successor, Major General Joseph Momoh.

In his first years Momoh took steps to reform politics and create a more open system of government. He set up a commission to explore a return to multiparty politics and draft a new constitution. He also addressed the nation's growing economic problems by creating a program designed to control government expenditures and increase revenue. Momoh's plans were disrupted in 1991 when Liberian rebel leader Charles Taylor invaded Sierra Leone.

Descent Into Chaos

Joining Taylor in his invasion was a Sierra Leone rebel group known as the Revolutionary United Front (RUF). Together, these forces quickly overran the countryside and captured Sierra Leone's diamond mining areas. Nigeria and Ghana sent troops to support the Sierra Leonean army, but they had little success against Taylor's guerrilla soldiers. Amid growing turmoil, a military coup led by Captain Valentine Strasser overthrew Momoh in 1992.

Despite initial victories against Taylor and the RUF, Strasser was no more effective than Momoh at ending the civil war. By 1994 rebel forces controlled the interior of Sierra Leone, and within a year they held major mining facilities, cutting off a crucial source of the nation's income. By 1995 the country was overrun by independent warlords and bandit groups in addition to the RUF. The government controlled only Freetown, and the economy was devastated. A 1996 coup toppled Strasser, and despite the continued fighting, elections were held in March of that year.

Only six months later, however, another coup ended the rule of the new civilian president, Ahmed Tejan Kabbah. The leaders of the coup freed from prison Major Johnny Paul Koroma, who was awaiting trial for an earlier coup attempt against Kabbah. Koroma ruled Sierra Leone for a year as head of an armed forces council. During this time the country slipped into anarchy. Freetown was engulfed in violence, including looting by soldiers and rebels.

After ten long months of fighting, troops provided by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) drove Koroma out of Freetown and restored Kabbah as president. Still, the fighting continued, and in January 1998 Freetown suffered another devastating attack that destroyed a fifth of the city's buildings. The international community finally intervened, pressuring both sides to find a solution, and peace talks were scheduled for the spring of 1999.

The Lome Accord. In July 1999 the RUF and the government of Sierra Leone signed a peace treaty in Lome, the capital of TOGO. According to the terms of the agreement, Kabbah ruled as president but shared power with RUF leader Foday Sankoh and Johnny Paul Koroma.

The Lome Accord also called for rebel soldiers to turn in their arms and return to civilian life. All who had taken part in the fighting were granted amnesty. Since the signing of the agreement, United Nations forces have replaced ECOWAS troops as peacekeepers, and there have been plans for a war crimes trial to prosecute rebels for atrocities against civilians. Meanwhile, RUF forces continue to hold parts of the country, and Liberia's president Charles Taylor continues to be a destabilizing force in the region.

THE ECONOMY

Before the outbreak of war in 1991, the economy of Sierra Leone was based on agriculture and mining. Agriculture employed most of the population, with coffee and cocoa being the main export crops. The bulk of the nation's export revenues came from the mining of diamonds, iron ore, and the mineral rutile, a form of titanium.

The civil war has ravaged Sierra Leone's economy. Fighting in rural areas drove many people off the land and into the cities. As a result most of the best farming land remains unplanted, leaving major agricultural areas out of production. Rebel forces control the mining industry and earn money from smuggling diamonds and mineral ores to Liberia and other neighboring countries. The prospects for economic improvement in the short term are dim.

PEOPLES AND CULTURES

The majority of the people of Sierra Leone are rural dwellers who depend on subsistence farming for a living. Some 60 percent belong to the Mende and Temne ethnic groups, and about 10 percent are Krio. The rest of the population consists mostly of other West African groups.

Political relations in Sierra Leonean society have traditionally revolved around who receives and who provides tribute. The tribute takers have usually been those in power, who are also responsible for distributing wealth and ensuring the fertility of the land and people. This social relationship has broken down in recent years, largely as a result of widespread government corruption and the violence unleashed by the civil war. A small educated group continues to control Sierra Leone and most of the nation's wealth, while the rural population struggles just to survive. The result is a massive social and economic divide within the country. (See also Colonialism in Africa, Creoles, Genocide and Violence, Lebanese Communities, Slavery, United Nations in Africa, Warfare.)