The Republic of Togo

POPULATION: 7.115 million (2014)

AREA: 21,930 sq. mi. (56,790 sq. km)

LANGUAGES: French (official), Ewe, Mina, Kabye, Dagomba, Komkomba

NATIONAL CURRENCY: CFA franc

PRINCIPAL RELIGIONS: Traditional 70%, Christian 20%, Muslim 10%

CITIES: Lome (capital), 513,000 (1990 est.); Sokode Palime, Atakpame, Bassari, Tsevie, Anecho

ANNUAL RAINFALL: Ranges from 40 in. (1,020 mm) in the north to 70 in. (1,780 mm) in the south.

ECONOMY: GDP $4.518 billion (2014)

PRINCIPAL PRODUCTS AND EXPORTS:

- Agricultural: cocoa, coffee, cotton, yams, cassava, corn, beans, rice, millet, sorghum, livestock, fish

- Manufacturing: food processing, cement, textiles, beverages

- Mining: phosphates

GOVERNMENT: Independence from French-ruled UN trusteeship. Republic under transition to multi-party democratic rule; president elected by universal suffrage. Governing bodies: National Assembly (legislative body) elected by popular vote; Council of Ministers and prime minister appointed by the president.

HEADS OF STATE SINCE INDEPENDENCE:

- 1960–1963 President Sylvanus Epiphanio Olympio

- 1963–1967 President Nicolas Grunitzky

- 1967– President General Gnassingbe Eyadema

ARMED FORCES: 7,000 (2001 est.)

EDUCATION: Compulsory for ages 6–12; literacy rate 52%

A small, narrow country on the Gulf of Guinea, Togo got its name from the Ewe words to, meaning “water”, and go, meaning “coast” or “bank”. During the colonial period it was controlled by a succession of European powers—Germany, Britain and France, and then France alone. For most of the time since its independence in 1960, the country has been ruled by one-party government and military dictatorship.

GEOGRAPHY

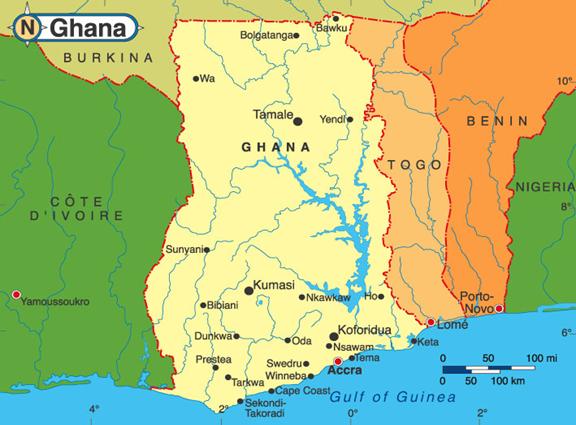

Togo lies on the southern coast of the West African bulge, between BENIN and GHANA. BURKINO FASO borders the country to the north. Only about 30 miles wide, Togo's coast is usually hot and humid and experiences two rainy seasons per year. Farther north, the climate becomes cooler and drier, and the country widens to its maximum breadth of about 100 miles. Overall, Togo's climate is considerably drier than that of its neighbors in the region.

Four major rivers flow though the narrow land of Togo. Most of the country is flat, but a range of low mountains runs along the western border with Ghana. The country's highest point is Mount Agou, rising to 3,225 feet. Swamp and rainforest dominate the south, while grassland covers most of the north.

HISTORY AND GOVERNMENT

People first settled in northern Togo between A.D. 600 and 1100. The southern region was populated around the 1100s and 1200s, when Ewe groups moved into the area from NIGERIA. Over the next several centuries, many different ethnic groups migrated into what is now Togo.

Colonial Rule

Although Portuguese navigators were the first Europeans to visit the region around 1471, it was Germany that eventually colonized Togo. In 1884 the Germans, who were looking for access to the NIGER RIVER, signed a protectorate agreement with Chief Mlapa III in the coastal town of Togo. Thirteen years later the Treaty of Paris confirmed the borders of the German colony known as Togoland. At that time the colony included part of the Gold Coast, the area that is now Ghana.

To ship cash crops from the colony's interior to Europe, Germany built roads, railroads, and a broadcasting system. Most of the development took place in the south, while the north was largely neglected. Southern Togolese generally fared better under German rule than the country's northern peoples. Many even obtained posts in the colonial government.

Shortly after World War I broke out in 1914, English and French troops occupied Togoland. After the war it was divided between the occupying powers. France received the larger, eastern portion of the territory, while England took control over the western portion. The southern portion of the country continued to benefit most under British and French rule.

The breakup of Togoland divided members of its main ethnic groups, the Ewe in the south and the Konkomba in the north, between the two new colonies. Each of the colonies experienced ethnic tensions between these rival groups as well as calls to unify British and French Togoland. However, in 1956 the majority of the inhabitants of British Togoland voted to become part of the British colony of Gold Coast. That same year, French Togoland voted to become a self-governing republic within the French Community and changed its name to the Republic of Togo.

Early Years of Independence

The 1956 election installed Nicolas Grunitzky as Togo's first prime minister. Two years later his brother-inlaw, Sylvanus OLYMPIO, succeeded him. When Togo gained its independence from France in 1960, Olympio became Togo's first president.

Hoping to free Togo from economic dependence on France, he championed a program of high taxes and trade restrictions. Although his plan balanced the budget, it was not popular—nor was the president's authoritarian rule.

In 1963 a military coup led by Sergeant Etienne Eyadema assassinated Olympio and replaced him with Grunitzky. However, after four years of little progress Eyadema overthrew Grunitzky and declared himself president. Hoping to unify Togo and to give the military a key role in politics, Eyadema created a party called the Rassemblement du Peuple Togolais (RPT). He proclaimed the RPT the nation's only legal political party and planned to use it to bring development to the long-neglected north, his homeland.

Eyadema's Rule

From 1970 to 1992 Eyadema ruled Togo without opposition. However, as corruption within his government weakened the country's economy, unrest grew. In 1985 a series of bomb attacks rocked the capital city of Lome. Eyadema began a campaign of killing and torturing anyone suspected of being against him, conduct that brought criticism from international human rights groups. When he accused Ghana and Burkina Faso of harboring political opponents, he strained Togo's relations with its neighbors as well.

In 1991 Eyadema responded to public pressure for multiparty democracy by establishing a one-year transition government. Talks were scheduled to discuss how a new political system would be put into place. However, one month after the conference began Eyadema cancelled it because it proposed taking away most of his powers.

Over the next two years, political violence tore the country apart and organized strikes brought the economy to a standstill. Between 200,000 and 300,000 Togolese fled the country. Opposition parties refused to participate in elections scheduled for 1993, which foreign observers claimed were tainted by voting irregularities. Eyadema won with over 95 percent of the vote.

The 1998 presidential elections were also unfair. Eyadema created new government bodies, filled with his supporters, to oversee preparations for the election. At the last minute, the election date was moved up two months to give opponents less time to prepare, and Eyadema again won the presidency. The following year the RPT swept legislative elections, although opponents claim that only about 10 percent of registered voters bothered to participate.

By 1999 the Eyadema regime had come under increasing fire from outside the country. Amnesty International, a leading human rights group, called Togo a “state of terror,” listing hundreds of political executions. Economic sanctions begun by the European Union (EU) in 1993 were hurting the economy.

In July 1999 Eyadema finally seemed willing to compromise, agreeing to discuss “national reconciliation” with his opponents in talks overseen by representatives from various European and African countries.

Eyadema promised to call new legislative elections in 2000 and create an independent electoral commission to oversee voting. However, Eyadema's opponents did not trust him and were unwilling to take part in political discussions. Doubts about Eyadema's sincerity about reforming the government were reinforced when the legislative elections planned for March did not occur.

ECONOMY

Like many of its West African neighbors, Togo's economy depends heavily upon agriculture. The vast majority of the workforce is employed in farming, which accounts for much of the country's gross domestic product (GDP). The main export crops are cotton, cocoa, and coffee.

Phosphates, used to make fertilizers, are the country's leading export. Although a rise in the price of phosphates during the 1970s promised to transform the economy, prices leveled off in the 1980s. Togo also manufactures a number of items for export including cement, refined sugar, beverages, footwear, and textiles. However, development of both new and existing industries is limited by the country's reliance on imported electricity. TOURISM, once an important industry for Togo, has declined since the mid-1980s because of the nation's political unrest.

PEOPLES AND CULTURES

Togo contains dozens of different ethnic groups. The Ewe and the Mina dominate the south. During colonial times, both of these groups profited from trade with Europeans and took advantage of commercial and educational opportunities. As a result they became the privileged classes after independence and still maintain that role, despite Eyadema's efforts to improve the position of northern peoples.

A great variety of ethnic groups live in northern Togo, including the Kabye, Komkomba Basari, Kotokoli, Tamberma, Tchokossi, Moba, and Gourma peoples. Many of these groups trace their language and cultural traditions to Burkina Faso. Northerners are mostly small-scale farmers, although some now work in the government. Some government workers are employed by the national government, while some are part of local authorities. At the local level, political figures often share power with a council of elders, who advise political and religious leaders to aid in decision-making. In addition, in some northern areas, there is a figure known as an “earth priest” who holds a position of authority and, at times, conducts rituals that ensure the fertility of the land and good crop harvests. The most prominent northern people are the Kabye, largely due to the fact that Eyadema claims Kabye descent.

About 70 percent of all Togolese practice traditional African religions. Some 20 percent are Christian, mostly Roman Catholic. Togo has relatively few Muslims, but Islam is growing in popularity. As in many African countries, those who practice Christianity and Islam also mix in elements of traditional worship. (See also Colonialism in Africa, West African Trading Settlements.)