Art

Each of the hundreds of different cultures in Africa has its own artistic traditions and its own ideas of what is beautiful or important. Variations in the style and form of artworks, as well as in the materials used to produce them, reflect such factors as a region's geography and climate, its social customs, and the available technology. Of course, the skill and tastes of individual artists—and the purpose for which the work is created—also play a role in shaping the final product.

OVERVIEW OF AFRICAN ART

African art takes many forms, from sculpture and paintings to masks, textiles, baskets, jewelry, and utensils. Artistic style also covers a wide range, from lifelike representations of people or animals to abstract geometric patterns. The YORUBA of Nigeria and the Bamileke of Cameroon, for example, believe that sculptures should resemble their subjects and must also show certain ideal qualities such as youth and beauty. The BAMBARA of Mali favor geometric shapes and idealized images over realistic portrayals of people or animals.

In sub-Saharan Africa, many art objects are created to serve a particular purpose. These purposes include dealing with the problems of life, marking the passage from childhood to adulthood, communicating with spirits, and expressing basic beliefs. Artists carve figures to honor ancestors, rulers, and gods. They make masks for use in rituals and funerals and for entertainment. They design jewelry and body painting that often function as a sign of wealth, power, and social position.

In North Africa, Islamic beliefs restrict the creation of images of living things. As a result, artists have applied their skills to decorative arts such as carpet weaving and calligraphy, or ornamental writing. Calligraphy can be seen on buildings, household items, sacred books, and other places.

Meaning in African Art

The subject of a work of art and the way in which it is made often have an influence on its meaning. In some cases, objects of great social and ritual significance have to be assembled according to certain procedures. Following the rules ensures that the piece will be filled with the appropriate “power.” If the rules are broken, the artwork loses its power and becomes an ordinary object. In other cases, the power is given to the object after it is completed. Some objects serve as a base for materials that add to their significance. For example, when a carver makes a mask, village elders may contribute medicines or herbs to give the mask power. The resulting piece is considered to have a personality of its own.

Design and decoration play a major role in the meaning of an object. An artist may make a mask large to indicate that it is important and add a prominent forehead to suggest that the mask is swollen with spiritual power. Certain patterns have particular significance, perhaps standing for water, the moon, the earth, or other ideas. Objects that represent spirits or spiritual powers are often abstract because the things they represent are abstract. Figures that represent living rulers tend to be more realistic to make it possible to recognize the individual's features. Some objects include symbols that represent powerful animals.

In one type of African art, forms that have known meanings are used in creating images of figures and ideas. The purpose is to portray rulers or ancestors as superhuman and, at the same time, to communicate a sense of permanence. Another category of art includes sculptures and masks that represent the visible world but refer as well to an unseen world behind them. These objects may be used in activities such as healing ceremonies and divination.

A third type of African art consists of everyday objects, such as spoons, pots, doors, cloths, and so on. Some of these items have elaborate decorations, such as the intricate human faces carved into the handles of wooden ladles from Ivory Coast. Often reserved for the wealthy, these objects can also be markers of social position.

Collecting African Art

Europeans began collecting African artworks as early as the 1600s, and by the 1800s interest in these objects was high. However, the first African pieces brought to Europe were regarded as curiosities rather than works of art. While admiring the workmanship, some people considered African art to be “primitive” and without artistic value. Nevertheless, by the end of the 1800s many European museums had acquired African pieces for their collections, usually to show everyday life in their countries' colonies.

African works did not attract much attention as art until the 1920s, when interest focused mainly on sculptures in wood and bronze. Since the 1950s Western collectors, scholars, and museums have come to recognize more and more African objects as valuable works of art. Prices of these works have risen accordingly.

In the early years, European museums often displayed African objects with exhibits of animals, rather than with other works of art. Today, museums present African pieces in their art collections. Furthermore, collectors now understand that, although individual works are not signed, many African artists are well known in the continent by name and reputation.

Art collecting has also changed in Africa. In the past, Africans sometimes threw objects away when they were thought to have lost their power. Without a specific function, the items had little value. Recently, however, more Africans have begun to collect works of art and a number of museums have been established on the continent with collections of African art.

Recent African Art

Over the centuries, African art has changed with the times. Not surprisingly, modern African society and culture are reflected in the recent work of African artists. Some of the religious rituals and other traditional activities for which African art was created no longer exist. Furthermore, new traditions, such as those connected to the practice of Christianity, have been introduced. Some artists have combined African ideas and Christian themes in their work. Others have produced pieces with African motifs and designs that are not intended for use in rituals. Yet, though much of the current art reflects modern concerns and issues, traditional art forms continue to play a meaningful role in the lives of ordinary people.

Styles of art change as well. Traditional designs often appear in new ways, such as using body painting designs in paintings on canvas. Perhaps one of the most notable features of recent African art is its role in the modern marketplace. In many places, an art industry has developed to produce objects specifically for Western tourists and collectors. Such “tourist” art may include copies of older art forms as well as contemporary designs.

SCULPTURE

For sculpture, perhaps sub-Saharan Africa's greatest art form, the most commonly used materials are wood and clay and metals such as iron, bronze, and gold. Unfortunately, wood decomposes and is easily destroyed, so few pieces of early wooden sculpture have survived.

West Africa

Sculpture is one of the major art forms in West Africa. Scholars divide the artistic traditions of the region into two broad geographical areas: the western Sudan and the Guinea Coast. Although some common themes appear in the art of these areas, the most striking feature of West African sculpture is its diversity.

The western Sudan, a savanna region that extends across West Africa, includes several well-defined sculptural traditions. Figures from this region often have elongated bodies, angular shapes, and facial features that represent an ideal rather than an individual. Many of the figures are used in religious rituals, and they often have dull surfaces encrusted with materials placed on them in ceremonial offerings.

The Mande-speaking peoples of the western Sudan create wooden figures with broad, flat surfaces. The body, arms, and legs are shaped like cylinders, while the nose may be a large vertical slab. Artists often burn patterns of scars—a common type of body decoration—into the surface of figures with a hot blade. Scar patterns also consist of large geometric shapes. The Mande wooden figures are usually dark brown and black.

Another important sculptural tradition of this region is that of the Dogon people of Mali. Much Dogon sculpture is linked to ancestor worship. The Dogon carve figures meant to house the spirits of the dead, which they place on family shrines. Their designs feature raised geometric patterns, such as black-and-white checkerboards and groups of circles in red, white, and black.

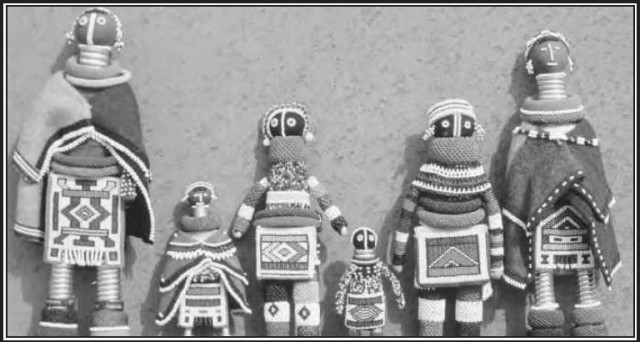

The Guinea Coast extends along the Atlantic Ocean from Guinea-Bissau through central Nigeria and Cameroon. Sculptural figures of this region tend to be more realistic in design than those from other parts of West Africa. The arms, legs, and bodies of figures are curved and smooth. Detailed patterns representing body scars—also typical of this region—rise above the surrounding surface. Many figures are adorned with rings around the neck. A common form of body adornment, the rings are symbols of prosperity and well-being.

Two noteworthy sculptural traditions of the Guinea Coast are those of the ASANTE (Ashanti) and the Fon. The Asante carve dolls that represent their idea of feminine beauty. They also produce swords and staffs, covered in gold foil, for royal officials. The Fon people are known for their large copper and iron sculptures of Gun, the god of iron and war.

The artistic traditions of Nigeria are very old indeed. Among the earliest sculptures from northern Nigeria are realistic clay figures of animals made by the Nok culture as early as the 400s B.C. The human figures produced by the Nok, with their tube-shaped heads, bodies, arms, and legs, are less realistic. The ancient kingdom of Benin in Nigeria was renowned for its magnificent brass sculptures. Dating from about the A.D. 1400s, these include images of groups of animals, birds, and people.

Another important sculptural tradition is that of Ife, an ancient city of the Yoruba of southwestern Nigeria. Between A.D. 1100 and 1450, the people of Ife were creating realistic figures in brass and clay, and some of these probably represent royalty. Life-sized Yoruba brass heads from this time may have played a role in funeral ceremonies. Yoruba carvings typically portray human figures in a naturalistic style. The sculptural traditions of Ife are still followed, but individual cults often have their own distinct styles.

Central Africa

Central Africa, a vast area of forest and savanna that stretches south from Cameroon to Angola and west to the Democratic Republic of Congo, contains a great diversity of cultures and arts. Yet, in most cases, the differences in artistic styles are so striking that experts have no trouble identifying the area where an object was produced.

A number of groups in Central Africa have ancient sculptural traditions, and some of the most impressive carving in Africa comes from this region. Pieces range from the wooden heads made by the Fang people to the royal figures carved by the Kuba to guard boxes of ancestral relics. The Kuba figures are decorated with geometric patterns and objects symbolizing each king's accomplishments. The Kuta-Mahongwe work in a more abstract style to produce guardian figures covered with sheets of brass or copper.

The varied sculpture of Central Africa does have some characteristic features, such as heart-shaped faces that curve inward and patterns of circles and dots. Some groups prefer rounded, curved shapes, while others favor geometric, angular forms. Specific details are often highlighted.

Particularly striking are the richly carved hairdos and headdresses, intricate scar patterns and tattoos, and necklaces and bracelets. Although wood is the primary material used in carving, the people of this region also create figures from ivory, bone, stone, clay, and metal.

Eastern Africa

Although sculpture is not a major art form in eastern Africa, a variety of sculptural traditions can be found in the region. An unusual sculptural form in some parts of eastern Africa is the pole, which is carved in human shape and decorated. Usually associated with death, pole sculptures are placed next to graves or at the entrances to villages. Among the Konso of Ethiopia, for example, the grave of a wealthy, important man may be marked by a group of carved wooden figures representing the deceased, his wives, and the people or animals he killed during his lifetime.

Sculpture is mainly associated with the dead in parts of Madagascar as well. Figures are often placed on tombs or in shrines dedicated to ancestors. The tombs of prominent Mahafaly individuals may be covered with as many as 30 wooden sculptures. Carved from a single piece of wood, each sculpture stands about 61/2 feet high. The lower parts are often decorated with geometric forms, while the tops are carved with figures of animals, people, and various objects.

Southern Africa

Sculpture does not have a particularly strong tradition in southern Africa. The oldest known clay figures from South Africa, dating from between A.D. 400 and 600, have cylindrical heads, some with human features and some with a combination of human and animal features.

Among the more notable carved objects found in southern Africa are wooden headrests in various styles from geometric designs to more realistic carvings of animal figures. Some headrests were buried with their owners, and some were handed down from one generation to the next.

MASKS

Masks are one of the most important and widespread art forms in sub-Saharan Africa. They may be used in initiation ceremonies, such as that marking the passage from childhood to adulthood. Masks also serve as symbols of power to enforce the laws of society.

Masks are usually worn as disguises in ceremonies and rituals, along with a costume of leaves, cloth, feathers, and other materials. Although masks may represent either male or female spirits, they are almost always worn by men. The person wearing the mask in the ceremony is no longer treated as himself or herself but as the spirit that the mask represents.

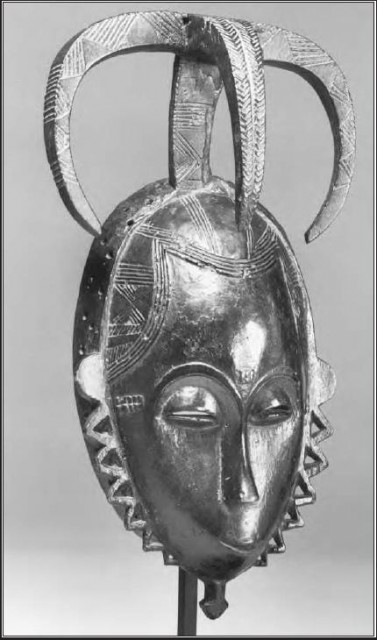

In addition to face masks (which just cover the face), there are helmet masks (which cover all or most of the head) and crest masks (worn on top of the head like a headdress). Made of wood, clay, metal, leather, fabric, or other materials, masks may be painted and decorated with such things as animal skins, feathers, beads, and shells.

West Africa

Many different forms and styles of masks can be found in West Africa. The Bambara people of Mali have specific masks for their various male societies. Many of these masks represent animals that stand for mythical characters. The masks are decorated with real antelope horns, porcupine quills, bird skulls, and other objects. The characteristics of several animals are combined in masks of the Senufo people of Ivory Coast.

Masks play a role in rituals and ceremonies related to death or ancestors. Once a year, in elaborate performances honoring their ancestors, the Yoruba of Nigeria put on masks made of colorful fabrics and small carved wooden heads. In other parts of Nigeria, masks representing both human and animal characters are worn at the funerals of important elders as a way of honoring the deceased.

The IGBO people of Nigeria have two types of masks to mark the transition from childhood to adulthood. Dark masks represent “male qualities” such as power and strength, prosperity, and impurity, while delicate white masks symbolize “female qualities” of beauty, gentleness, and purity. Among the Mende people of Sierra Leone, elaborate black helmet masks representing the Mende ideals of feminine beauty are used in rituals initiating young girls into womanhood. This is the only case of women wearing masks in Africa.

Central and Eastern Africa

Many Central African masks signify rank and social position, representing the authority and privilege of kings, chiefs, and other individuals. Some also function as symbols of identity for specific groups. While certain masks are considered the property of individuals, others are owned collectively by the group. Used in a variety of situations, masks may inspire fear, fight witchcraft, or entertain. As elsewhere in Africa, many masks are linked with initiation and funeral rituals.

Among the most notable masks of Central Africa are large helmet masks with figures of humans, animals, and scenes on top. Too heavy to be carried or worn, they are displayed during important ceremonies. The masks of the Pende people of Angola and Congo (Kinshasa) are among the most dramatic works of art in Africa. These large helmet masks have faces with angular patterns and heavy triangular eyelids. Topped by plant fibers that represent hair, they are thought to possess mysterious powers. The Pende make smaller versions of these masks in ivory or wood for use as amulets. In nearby Zambia, various materials are used to create ceremonial masks. The Mbundu work in wood, and the Luvale and Chokwe attach pieces of painted bark cloth to a wicker frame.

Masks do not play an important role in the art of eastern Africa. However, the Makonde of Mozambique and southeastern Tanzania create distinctive face masks and body masks.

PAINTING

Painting on canvas is a recent development in Africa. Although Africans have always painted, they have done so primarily on rock surfaces or on the walls of houses and other buildings. Africans also apply paint to sculpted figures, masks, and their own bodies.

The earliest known African paintings are on rocks in southern Africa. Made by the KHOISAN people about 20,000 years ago, these rock paintings portray human and animal figures, often in hunting scenes. The paintings may have had ritual or social significance, though no one knows for sure. Other ancient rock paintings have been found in the Sahara desert in North Africa. Dating from as early as the 4000s B.C., these paintings also portray animals and human figures. The strongest traditions of rock painting are found in eastern and southern Africa.

Eastern Africa

The people of eastern Africa have traditionally painted and marked their bodies in various ways. Such decoration has been considered a sign of beauty as well as a form of artistic expression. Some of it is temporary, as in the case of body painting with various natural pigments and other coloring agents. The patterns and designs used often signify group identity, social status, and passage through important stages in life.

Other forms of painting can be found in Ethiopia. Christian influence has been strong in Ethiopia for centuries, and around the A.D. 1100s Ethiopian artists began painting religious scenes on the walls of churches. Since the 1600s, Ethiopians have also produced religious pictures on canvas, wood panels, and parchment.

Traditions of painting are found in several other areas of eastern Africa as well. The Dinka and Nuer people of southern Sudan, for example, paint pictures of cattle and people on the walls of huts. Members of the secret snake charmer society of the Sukuma people in Tanzania decorate the interior walls of their meetinghouses with images of humans, snakes, and mythological figures. The LUO of western Kenya paint geometric designs on fishing boats, and the Mahafaly of Madagascar paint scenes on the sides of tombs.

Southern Africa

Wall painting on the interiors or exteriors of buildings is an important art form in southern Africa. Some very striking examples can be found in this region. Among the best known are those of the NDEBELE of South Africa and Zimbabwe. Almost exclusively the work of women, these paintings were traditionally done in natural earth colors using bold geometric shapes and symmetrical patterns. In recent years, Ndebele women have also used commercial paints, and their designs have become more varied, incorporating lettering and objects such as lightbulbs, as well as abstract designs.

DECORATIVE ARTS

The decorative arts include such items as textiles, jewelry, pottery, and basketry. While viewed as crafts in some Western cultures, these objects can also be seen as works of art because of the care and level of skill that goes into their creation.

Many useful objects are carved from wood or other hard materials and then decorated. The SWAHILI of eastern Africa used ivory and ebony (a hard wood) to build elaborate “chairs of power” with footrests and removable backs. In West Africa, some Nigerian artisans make musical instruments and food containers from round fruits known as gourds. The outer surfaces of the gourds are covered with delicately carved and painted geometric designs.

African artists create jewelry for adornment, as symbols of social position, and even to bring good health and luck. They use materials such as gold, silver, and various types of beads to make necklaces, bracelets, crowns, rings, and anklets. In the KALAHARI DESERT in southern Africa, artisans fashioned ornaments with beads made from glass or ostrich eggshell. In West Africa the Asante are famous for their gold jewelry and gold-handled swords.

The Asante are also skilled weavers, known for their kente cloth—richly colored cotton or silk fabrics. Many groups of people in western and central Africa have developed their own weaving traditions, using particular types of looms and decorative techniques such as embroidery, patchwork, painting, stenciling, or tie-dyeing. Weavers use cotton, wool, wild silk, raffia, or synthetic threads to create their designs. In Niger, the Zerma weave large cotton covers in vivid red and black patterns. The Mandjak of Senegal produce magnificently colorful cloth of synthetic silk, rayon, or lurex fibers.

In North Africa, one of the most important decorative art forms is calligraphy. Calligraphy has special significance for Muslims because they consider the written word a sacred symbol of Islamic beliefs. In addition, because of the restrictions on creating images of human beings, artists turn to calligraphy to decorate their work. Calligraphy is found on buildings throughout North Africa and on many objects used in daily life. Carved in wood and stone, painted on walls and pottery, burned into leather, woven into cloth, or shaped into jewelry, calligraphy appears in a wide variety of materials and styles. Geometric designs or flowing patterns of lines and curves resembling flowers, leaves, vines, and even animals often accompany the calligraphy. These designs are always highly stylized, not realistic in form.

Rugs are another major art form in North Africa. The production of intricate hand-knotted rugs began to flourish in Egypt in the 1400s under the Muslim Mamluk rulers. Early rugs featuring a central design surrounded by border elements sometimes contained as many as six colors. Woven carpets are produced in many areas of North Africa, including Sudan and Morocco, often by groups of BERBERS. (See also Architecture, Body Adornment and Clothing, Crafts, Ethnic Groups and Identity, Festivals and Carnivals, Houses and Housing, Initiation Rites, Masks and Masquerades, Religion and Ritual, Rock Art, Spirit Possession, Witchcraft and Sorcery.)