Chronic Disease

Introduction

Chronic diseases are ongoing/recurring, not caused by infection, or passed on by contact. They generally cannot be prevented by vaccines, do not resolve spontaneously, and are rarely cured by medication or other medical procedures. Chronic diseases are often caused by a combination of health damaging behaviors (smoking, drinking, high fat diet, and physical inactivity) and exposure to socioenvironmental conditions (stressful living circumstances, poverty, and automobile focused urban centers). The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies four main types of chronic diseases – cardiovascular disease (CVD; primarily heart disease and stroke), cancer, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes – responsible for the majority of related deaths. However, mental disorders, vision and hearing impairment, oral diseases, bone and joint disorders, and genetic disorders are also noted as chronic diseases that account for a substantial portion of the global burden of disease.

The Global Burden

Chronic diseases are the largest cause of mortality in the world, accounting for close to half of the world's deaths. The greatest contributor to this burden of illness is CVD, followed by cancer, chronic lung diseases, and finally diabetes mellitus. The picture of health has not always been this way. Many countries in the developed world have 'achieved' what is known as 'the epidemiologic transition', that is, the health status and disease profile of human societies have historically been inextricably linked to their level of economic development and social organization; when we lived as hunter gatherers, we had very high birth rates as well as high death rates. Major causes of death were starvation, warfare, interactions with fierce animals, high rates of maternal and child mortality, as well as frequent epidemics of infectious diseases and famines. Healthcare systems at this time represented indigenous systems, traditional healers, and herbal medicines. As we organized ourselves into agrarian societies, we had better access to food and therefore birth and death rates began to fall near the end of this period. High rates of fertility continued given persistent high rates of infant mortality and the need for farm labor, but both of these, as we saw, fell tremendously during the Industrial Revolution. Deaths from infectious diseases decreased dramatically, standards of living increased accordingly, and families therefore gave birth to fewer children. Farming practices became mechanized, more food was being produced for fewer people, and all in all people lived longer and healthier lives. While there is some suspicion that the primary reason for this shift in stage 3 was the development of, and increased access to, a modernizing healthcare system, others disagree. A historical epidemiologist named Thomas McKeown explored over 300 years of data to come to the conclusion that, indeed, healthcare and access to it had very little to do with the gains in health status the world saw during the 1800s and early 1900s. Rather, the primary contributors to enhanced health status were sanitation, improved nutrition, and family planning. Stage 4 in the epidemiologic transition represents our current state, where chronic diseases take the lead with respect to mortality and morbidity. The literature often refers to these as 'diseases of affluence' given that as a human society, the higher our standard of living and the more progressive our economic development, the more likely we are to die of a chronic (as opposed to infectious) disease. Now we start seeing deaths overtaking births in many parts of the world. The explanation for this is that women are more educated, take a full role in the workforce, and are choosing to have fewer children. Fertility is, therefore, at below replacement levels (e.g., see the population trends in Greece, France, and Germany). As a result, some countries have to rely heavily on immigration to fuel their economies. As we live longer, and make more money, rates of chronic diseases increase, due to the role of lifestyle (smoking, drinking, high fat diets, and lack of physical activity) and environmental (automobile based cities) factors. The final stage of the epidemiologic transition predicts effective chronic disease management that would see a substantial reduction in mortality from chronic disease. But we have to die sometime, of something. Researchers predict we reach our 'biological wall' at about 85 years. So, the true pattern of stage 5 is yet to be determined.

Regardless, the global prevalence of all the leading causes of chronic diseases is increasing, with the majority occurring in developing countries and projected to increase substantially over the next 20 years. Chronic diseases have not simply displaced acute infectious diseases as the major cause of death in most developing countries, but they have joined them. As a result, such countries now experience a double burden of disease; a polarized distribution of ill health, if you will, that makes any policy response that much more complicated. For example, in South Africa, infectious diseases account for 28% of years of lives lost while chronic diseases account for 25%. This distribution of disease can put a tremendous strain on any healthcare system. Further, this polarized distribution creates unhealthy, unintended consequences. For example, antiretroviral regimens in HIV infected patients actually 'increase' the risk of CVD. Despite this increasing burden of disease, WHO spends only 50 cents per death per person on all noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) except for mental health; it spends a comparative $7.50 on leading communicable diseases.

Determinants of Chronic Disease

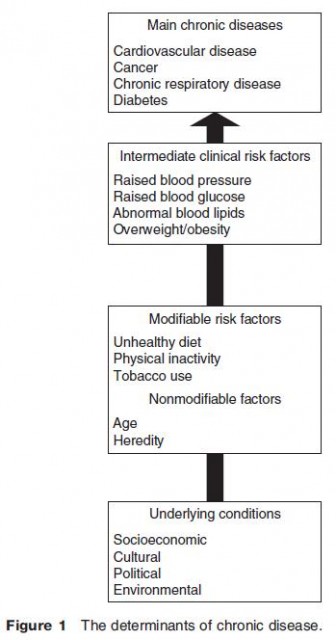

Although chronic diseases are among the most common and costly health problems in the world, they are also among the most preventable. A small set of risk factors explains the majority of chronic disease occurrence at all ages and for both sexes. Four of the most prominent chronic diseases – CVDs, cancer, chronic lung disease, and diabetes – share common and preventable biological risk factors, specifically high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, and overweight (Figure 1). These intermediate, clinical risk factors are related to three modifiable behavioral risk factors – unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and tobacco use – as well as nonmodifiable risk factors (age and heredity).

These modifiable risks are not solely determined by individual lifestyle choices, but are rather shaped by underlying socioeconomic and environmental conditions. The underlying determinants of chronic diseases are a reflection of larger societal and institutional forces driving social, economic, and cultural change such as globalization, urbanization, population aging, and policy structures.

Greater exposure to physical risks, higher levels of psychosocial stress, and lack of access to healthcare make those living in poverty even more vulnerable to chronic disease; further, the experience of chronic illness can also push families into poverty.

A range of other factors contributes to a much smaller proportion of chronic disease such as excessive alcohol use and infectious agents (related to cervical and liver cancers). Physical environmental factors (such as air pollution) also cause several chronic respiratory diseases. Finally, genetics and psychosocial factors (such as stress) also play a role, although their interaction with other determinants is more complex.

A growing body of research, based on chronic disease epidemiology from a life course perspective, has demonstrated the critical role of conditions in particular life stages in determining chronic disease. In particular, prenatal (maternal health, nutrient intake, and exposure to harm) and early childhood conditions (diet and socioeconomic conditions) are associated with rates of chronic disease in adulthood.

Geographies of Chronic Disease

Geographers have contributed to our understanding of chronic disease in a number of ways: distribution and diffusion through disease ecology approaches, the use of geographic information systems (GISs) and spatial analysis, contributing to our understanding of determinants, highlighting the inequalities in mortality and morbidity, contributing to our understanding of the impacts of chronic disease on individuals, as well as more recently contributing to our understanding of prevention.

Disease ecology is a long standing branch of medical geography that focuses on the distribution and diffusion of disease. Simply mapping the incidence of mortality and morbidity from chronic disease – at various spatial scales (local, regional, national, and international) – can provide clues as to its etiology and treatment. In a sense, therefore, these types of investigations are primarily hypothesis generating. When we pair incidence data with potential determinants, we can start to test whether or not hypotheses have some credibility. For example, we can map data on the hardness of water along with incidence of mortality and morbidity from CVD to assess whether or not these two things are associated in space. Or, we can map air pollution data along with CVD data to assess the same (potential) association. The introduction of sophisticated GISs and spatial analytic techniques allows us to explore these relationships even further. Take for example the simple mapping of CVD incidence data. We can map rates for, say, Canada and the US. From this, we can develop a powerful visual display of where rates are high and where they are low. While interesting enough, the application of spatial analytic techniques such as local indicators of spatial analysis (LISA) allows us to create a simple coefficient that tells us whether or not the patterns we see in the map are occurring due to some systematic distribution or simply because of chance. This process of identifying 'hot spots' of disease then focuses researchers and policymakers on areas deserving of greater attention.

Geographers have also contributed substantially to our understanding of the determinants of chronic diseases and their associated risk factors. The importance of space and place underlies much of this work. For example, geographers have contributed to our understanding of the different pattern and intensity of risk factors in remote northern communities in Canada. More recently, geographers have been undertaking a substantial amount of research on the role of the built environment as a determinant of chronic diseases and their related risk factors. Using GIS to objectively measure features of the built environment, for example, we can see the relationship between the built environment and physical activity, a major risk factor for overweight and obesity, CVD, diabetes, and some cancers. Some geographers have explored the assessment of a 'walkability' index using GIS in residential neighborhoods, where 'walkability' can be defined as the extent to which characteristics of the built environment and land use may or may not be conducive to residents in the area who walk for exercise, recreation, or leisure in order to access amenities or travel to work.

Recent developments in the area of multilevel modeling have increased the capacity of geographers to explore not only the spatial distributions of (chronic) disease, but also their determinants at the individual and ecological levels. For example, health geographers have always been curious – in terms of the determinants of disease more generally – about the relative contributions of the characteristics of the individual (e.g., sex, age, and income) versus the characteristics of the neighborhood in which the individual lives (e.g., average income, average education, and average dwelling value).

With respect to inequalities in the burden of chronic disease, geographers have focused on a range of characteristics: socioeconomic status in general (income in particular), race, ethnicity, education, and geographic location. For example, researchers have found a distinct social gradient in the incidence of chronic disease by socioeconomic status, indicating a stepped gradient in incidence with decreasing status. Geographers in Canada have deconstructed this further to indicate that while income is a major determinant of chronic disease inequality in the US, education plays a greater role in the Canadian context. This may be due to the lack of universal health insurance in the US. Rates of chronic disease, and their associated risk factors, are also higher among certain racial and ethnic groups. For example, many African Americans suffer disproportionately from hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia (i.e., an abnormality related to fats or lipids in the blood), all of which are significant risk factors for CVD and some cancers. The primary factors contributing to this pattern could include chronic overweight and obesity, high salt intake, lack of adequate follow up, inadequate access to healthcare services, cost of treatment, etc. Further, geographic variation in mortality from chronic disease in African Americans has been the focus of several research studies, and substantial variation has been found. Similar results stem from studies of geographic variations in chronic disease rates among women, and particularly minority (i.e., African American and Hispanic) women. This translates to utilization of healthcare services for chronic diseases, with Hispanic women exhibiting very low rates of screening for breast cancer in the US.

While much of the above research in the geographies of chronic disease has employed quantitative method ologies, the use of alternative epistemologies by human geographers to explore the experiences of individuals diagnosed with a chronic disease has also contributed substantially to our understanding. These researchers focus on the meaning of chronic illness and the disruptions to life because of its onset. Major findings indicate a shrinking of geographical worlds as chronic illnesses progress and individuals find that the social and economic roles that they play(ed), as well as the spaces they inhabit(ed) begin to erode as working life and many aspects of social lives come slowly to an end as the chronic disease progresses.

Finally, health geographers have been moving into the area of chronic disease prevention and health promotion. Much of this work has focused on the capacity building efforts of both communities and public health systems in the context of chronic disease prevention. Health promotion specialists have begun to realize the importance of the environment (social, physical, and cultural) in the prevention of chronic disease and have begun to shift the emphasis from individual lifestyle type promotion activities (e.g., encouraging individuals to quit smoking) to community-based interventions and policies (e.g., bylaws around the use of and advertising for tobacco). Prevention efforts are discussed in more detail in the next section.

Response to the Burden

Chronic diseases have generally been neglected in international health and development work. This is due, in part, to the commonly held notion that chronic diseases mainly affect high income countries, when the majority of global deaths due to chronic disease actually take place in low and middle income countries. Chronic diseases hinder economic growth in all countries. However, it is especially important that prevention efforts are undertaken in both countries experiencing rapid economic growth (e.g., China and India) and those that are the least developed countries.

Integrated Approach to Chronic Disease Prevention

A significant percentage of deaths from cancer, heart disease, and diabetes could be reduced or delayed through primary prevention. Based on the commonality of risk factors and approaches across many chronic diseases, there is a growing recognition of the strong rationale for pursuing an integrated approach to prevention efforts. Although an elevation of a single risk factor significantly predicts individual's ill health, the societal burden from NCD results from the high prevalence of multiple risk factors related to general lifestyles. Community-based activities are required with an 'integrated' public health approach targeted to the population, in addition to those at high risk by linking prevention actions of various components of the health system, including health promotion, public health services, primary care, and hospital care. Integrated chronic disease prevention aims at intervention that addresses the common risk factors by the health system and other existing community structures, rather than an outside prevention program. It denotes a comprehensive approach, which combines varying strategies for implementation. These include policy development, capacity building, partnerships, and informational support at all levels. Integration also calls for intersectoral action to implement health policies. Finally, an integrated approach centers on strategic consensus building among different stakeholders, such as governmental, nongovernmental, and private sector organizations, in an effort to increase cooperation and responsiveness to population needs. The concept of an integrated approach is not a new one. It was first introduced by WHO in 1981 and later endorsed by the World Health Assembly in 1985, which led the WHO program to test and evaluate comprehensive, integrated, community-based approaches to chronic disease prevention and control (WHO's Countrywide Integrated and Non Communicable Disease Intervention (CINDI) Program).

Promotion of Health Equity

Traditionally, chronic diseases were considered diseases of affluence. Currently, there exists sufficient evidence to indicate that this relation has been inverted. Evidence clearly shows that the risk for some NCDs (such as CVD and certain forms of cancers) is now higher at lower socioeconomic levels.

Prevention strategies should consider underlying influences on health inequalities such as education, income distribution, public safety, housing, work environment, employment, social networks, and transportation among others. It is important that strategies are aimed at reducing overall population risk while simultaneously reducing the gap among different population groups. In many instances, this requires a redesign and an evaluation of interventions of well documented efficacy. It also entails the identification and special attention to key population groups, such as Indigenous Peoples, new urban migrants, and women.

Community-Based Interventions

Community interventions have demonstrated that they have a great effect on NCD prevention, since the interventions intend to act not only on the individual and its nearby social nucleus, but additionally on the social environment that determines behaviors. These interventions imply the active participation of families and communities, pooling and sharing resources to ensure integrated preventions, the identification of leaders, organized groups and institutions, and the development of strategic coalitions and alliances.

Looking Forward

Is the world close to achieving its demographic transition? Will infectious diseases be a thing of the past, with chronic disease rates putting an increasing strain on the world's economies and healthcare systems? Will the world end up with the bimodal health distributions seen in parts of Africa and other parts of the developing world? Will the stage of effective chronic disease management take root and bear fruit, altering the curve seen in stage 5 of the epidemiologic transition? These are only some of the questions that remain to be answered.

- Christian Geography

- Christaller, W.

- Choice Modeling

- Chinese-Language Geography

- The Persistence of the State in Chinese Urbanism

- Multiplex Urbanism in the Reform Era

- Socialist Urbanism (1949–1978)

- The Arrival of the West and Modernist Urbanism (1840–1949)

- Administrative and Commercial Urbanism (770 BC–AD 1840)