Critical Contemporary Aid Debates

Many critics have doubted the effectiveness of aid especially in the context of reducing poverty. Throughout the 1970s, the dependency theorists viewed aid as a source of exploitation and dominance by the northern countries. In the 1980s, ODA was challenged by the rise of the neoliberal agenda in the west as aid was now held to contribute to excessive government and harm economic markets.

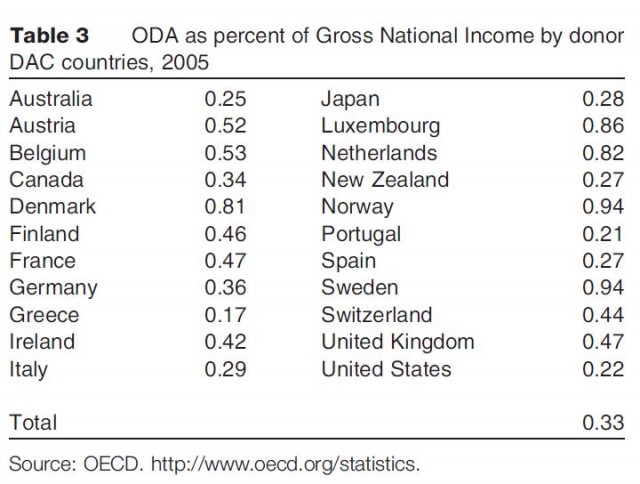

Currently, aid is viewed as a means of promoting donors' perceptions of 'good governance' and 'sound' economic practices, leading many analysts and politicians to become very critical of aid. Research has indicated that economic growth has taken place post structural adjustment and reforms. Good governance is defined as sound management of a country's economic and social resources for development. What is 'sound' for the World Bank and others holding the view that 'democratization stimulates development' is a range of management techniques that are believed to work well within a standardized liberal democratic model. Critics contend that there are, and ought to be, different paths for de velopment; they are not opposed to 'good governance' but urge that this is compatible with alternatives to liberal democracy in poor countries with different institutional contexts. Despite various campaigns led by various advocacy groups such as Jubilee 2000 and Make Poverty History urging for cancellations, progress on this front has been very slow. The campaign for debt cancellation has been based on the grounds that the original sums borrowed have been paid many times over, because of the interest payments attached to the principal sum. According to a report prepared by Oxfam, in 1998, African countries have spent four times more in debt payments to northern countries than on health and education. Not all countries in sub-Saharan Africa have high debt–GNP ratios, for example, Malawi, Chad, and Burkina Faso have generally been under 50% since the early 1990s. The contemporary language among donors is of building partnerships and building capacity within developing countries and with institutions rather than resting the burden of responsibilities on the recipient countries. Various initiatives such as the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative were announced at the G7 summit in 1997. It is believed that governance is the key to development. This is prominently highlighted in 2005 in the Commission for Africa report, Our Common Interest launched before the G8 summit at Gleneagles, Scotland, which pledged to double aid by 2010, including an extra $25 billion for Africa and debt write offs for 18 of the world's poorest countries. The EU pledged to increase aid to an average of 0.5% of GDP of member states; this challenges governments to absorb the cost of aid allocation (see Table 3 for current figures). Critics believe that this ODA is preventive investment in and beyond failed or fragile developing countries and aid is becoming part and parcel of a comprehensive security strategy for a donor's own country.

Institutional reform in developing countries, increasing the role of the private sector in the 1990s in public service delivery, has generated significant opposition and protest. It emphasizes the renewed interest of the markets in the development process, in the context of the state's failure and a possible to responds to the vast needs of the low income citizens of the developing countries. The search continues for combining the assumed efficiency of the private sector and the democratic accountability of the public bodies. In combining market economics and liberal democratic politics, NGOs are simultaneously viewed as market based actors and central components of civil society. NGOs fill gaps left by the privatization of state services as part of a structural adjustment or donorpromoted reform package. Governments need NGOs to help ensure their programs are effective, well targeted, and accessible to the poorest of the poor. It is now widely accepted that domestic ownership of policy reforms is crucial especially through local stakeholders and domestic leaders for effective implementation and that donor pressures lead to nationalistic resentment of donor interference and undermines the legitimacy of externally promoted policy reforms.

Nongovernmental development assistance organizations have delivered assistance, primarily at the local scale, to disadvantaged communities in developing countries. Their main aim is to contribute to improved quality of life for people in those communities. However, rather than continuing to concentrate on the 'development project' in order to provide services and alternative livelihood strategies, increasingly since 1990s, northern NGOs have devoted their energies and commitment to advocacy campaigns engaging. They have involved with global institutions and affecting on their policies to highlight wider structural factors which perpetuate poverty, for example, entrenched unfair terms of trade, poor commodity prices, or oppressive debt obligations. NGOs are lobbying for further cancellation of debt (Jubilee Debt Campaign) or eliminate poverty (Make Poverty History). NGOs are forging alliances and increasing their engagement in global networks and decision making processes.

While some see multilateral institutions such as the World Bank playing an important role in eradicating poverty, others see them as part of the problem. Multilateral institutions have to satisfy different constituencies such as the borrowing countries, donor countries, and increasingly NGOs and civil society. Hence, multilateral institutions are unable to articulate competing views. Gaining consensus is not easy and becomes an objective in itself while the kind of consensus established is based on the power relationships that prevail in the institutions themselves. Development is no longer just a matter of finding the right solution to the problem of persistent poverty in developing countries. In the contemporary world today, the challenge is to construct some sort of consensus around an increasingly politicized agenda constituted around a whole range of new crosscutting themes such as governance and indigenous people. It is no longer in any credible way possible to define development solely in a technical manner. An increasingly political agenda will make the process of political maneuvering between donor and recipient countries and other stakeholders (civil societies and the private sectors) increasingly difficult for multilateral institutions. They have been forced to face the criticism from a wide range of civil society stakeholders and have to respond to the emerging changes and challenges.

The achievement of development aid is difficult to assess. Many recent studies have tried to assess the effectiveness of aid. The purpose of giving ODA and its deployment is more open to scrutiny. One response has been increased funding for NGOs, generally thought more able to reach the local grassroots level.

Conclusion

There have been significant changes in the way aid is given, in the last 50 years. Our expectations of giving aid and what we understand about it has changed too over this period.

Aid in real terms and expressed as a percentage of donor wealth is declining, in contrast to increasing flows of private international finance. Issues such as global climatic changes, environmental threats, asylum seekers, internationally organized crimes drugs and people trafficking, international migration, and human suffering all have drawn attention to aid allocation policies. It is clear from the present instability, insecurities, and wars, that world leaders have to make a conscious effort in maintaining the multicivilization characteristics of global politics. Early warning systems for complex emergencies have to be adhered to and actions taken immediately. It remains to be seen if these wide ranging objectives can be achieved. Considerable efforts are being made to improve the effectiveness of aid but the outcomes are as yet unclear.

All aid agencies see poverty alleviation as the main priority. The problems it hopes to resolve are very complex which require multidisciplinary approaches. Perhaps we need to lower our expectations on what really is achievable through development aid.