Feedback Effects

Adherents of the revisionist approach emphasize the positive potential of skills out migration for Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The loss of the highly skilled may not always mean a loss for economic development. The revisionists assert that brain drain is a temporary stage and that a brain gain may actually result. Along with the migrant and receiving country, the developing country could be one of the three beneficiaries of a 'win win win' situation if skills migration is managed correctly. To understand how benefits could possibly be seen as accruing to source countries, it is necessary to consider what are referred to in the literature as 'feedback effects'.

Human Capital Development

One such effect is enhanced levels of human capital formation. In countries where skills emigration is prominent, these levels positively correlate with the probability of emigration. In other words, the prospect of emigration can act as a spur to personal skills development and training. Yet, the prospect of emigration often does not translate into actually leaving, resulting in what has been termed an optimal brain drain. Research on emigration potential in Southern Africa shows a major gap between the numbers of individuals thinking about or expressing interest in emigration and the numbers of those who actually leave. As long as the majority of better educated people do not emigrate, a net increase in education and human capital results. A study of 111 countries between 1960 and 1990 found that a 1 year increase in the average education of a nation's workforce increases the output per worker by between 5% and 15%.

Remittances

Research has clearly demonstrated that in a globalized migration system, those that leave do not automatically cut their ties with home. Indeed, the phenomenon of skills migration underlies the massive increase in the global volume of remittances in recent years. Remittances represent a significant portion of many nations' GDP, and globally account for twice the value of foreign aid. One study estimates that each remittance dollar 'multiplies' into $2 or $3 of gross national product (GNP) for the receiving country. The potential benefit of remittances is dependent on several factors, including how much and how often emigrants send them, what form they take, and where they are directed.

While they may remit less often than lower skilled migrants, skilled migrants are likely to send more money than lower skilled migrants because they tend to earn more. They also are more likely to direct remittances toward more productive (as opposed to consumptive) purposes, such as the purchase of bonds, the establishment of foreign currency accounts, or investment in business creation or philanthropic ventures. However, remittances tend to have greater developmental impact when they go to rural areas, which is not where highly skilled emigrants tend to originate.

Econometric studies suggest that, overall, remittances probably do not offset the adverse effects of skills migration. Furthermore, they may contribute to the dependency of developing countries on foreign sources of income. They amount to substantial and important portions of income for many countries, however, and should continue to be considered a loss mitigating factor.

Networks and Social Capital

While financial remittances should be considered, so should the networks that migrants and governments set up between home/sending and destination countries. Through these networks, migrants build social capital and transfer knowledge, which are critical for economic dynamism and institutional change. New technologies, management strategies, and trade opportunities can be diffused, contributing to the generation of new possibilities and economic growth. Emigrants can link domestic residents to international social networks, use their wealth to invest in home country projects, and act as transnational entrepreneurs. These connections and flows of ideas may have more significant long term consequences than remittances.

Some analysts, however, question the effectiveness of networks in meaningfully impacting economic development, pointing to the paucity of evidence of the success of expatriate knowledge networks in generating real net economic gains. The extent to which these networks can be established and utilized may be constrained by state limits in the receiving country on the power and scope of a diaspora's public activity because of security interests and by companies limiting the exchange of technical knowledge. Furthermore, knowledge exchange through diasporas about, for example, job markets and opportunities, may serve to further encourage skilled individuals to emigrate.

Whatever the actual impacts of diaspora behavior, migrants and immigrants do maintain closer ties with home than ever before leading to the phenomenon of 'transnationalism'. In a globalized world, many transnational migrants never really 'leave', literally living their lives between two places. Today's migrants are less likely to stay elsewhere permanently. With the help of improved transportation and communications technologies, many are able to travel back and forth relatively easily, to retain close contact with their home countries and communities and to build relations with other communities in third countries. The implications of transnational behavior for development in sending countries have yet to be fully realized or studied.

Return Migration

Finally, the potentially positive feedback effects of return migration should be considered. Many emigrants doeventually return to their country of origin, raising the possibility that the time spent away can be turned to the advantage of the home country. Indeed, some literature points to shifts from permanent to temporary migration and intrinsic intentions to return.

Some economists argue that return migration may be more effective in boosting development and wages than foreign assistance. This advantage can be garnered from the human, entrepreneurial, financial, and social capital that migrants may have accumulated while away. They may return with greater education and financial wealth, technological knowledge, different experiences and changed expectations, new ideas and international connections, and new investment channels, all of which can help spur development. Some benefits can accrue even if the return is temporary.

The benefits of return migration depend on a number of factors, however. First and most obviously, the number of returnees as a percentage of those that left is an important figure to consider, and the incidence of return varies greatly across regions and countries and itself depends on various factors. For the migrant, integration experiences and changes in migration plans play a role, as do the abilities of developing countries to generate the incentives required to entice their skilled emigrants to return home.

Other factors influencing the impact of return migration on development include: which migrants return (how skilled they are); the skills and knowledge acquired while away and the ability to transfer these upon return; how long a migrant has been away and how long he/she remains back home; and reasons or motivations for return.

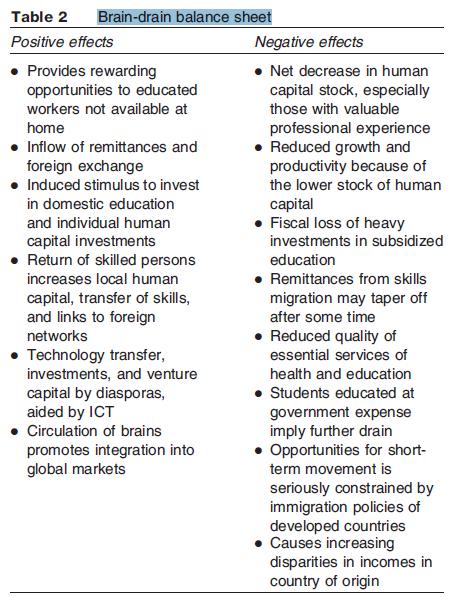

With all the absence, prospect, and feedback considerations factored in, the brain drain picture that emerges is quite complex. Piyasiri Wickramasekara presents a helpful brain drain balance sheet that offers a quick overview of the potential positive and negative effects for sending countries, which is reproduced here (Table 2).

Can countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America turn a brain drain into a brain gain through these feedback effects? On a balance sheet, for most countries, the answer would probably be no. Benefits tend to accrue more to large, relatively better off countries that have deliberate labor export policies, and to elites in these countries. The feedback effects of brain drain do not generally relieve pervasive poverty and inefficient use of human resources, or promote more equitable long term development in every developing country.