Leonhard Fuchs, Fuchsia, and the First Botanical Glossary

It is the custom for botanists to honor distinguished members of their profession by naming plants for them. The fuchsia is a popular ornamental shrub, grown for its flowers and as a hedging plant. The French botanist Charles Plumier (1646–1704) was the first European to discover it. In 1696–97 Plumier found it growing wild on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola (occupied by the Dominican Republic and Haiti). Fuchsia can also be found in tropical and subtropical Central and South America and in New Zealand and Tahiti. The cultivated plant is one of about 100 species in the genus Fuchsia belonging to the evening primrose family (Onagraceae). The cultivated plant was introduced to Europe and North America, and it has escaped from cultivation and become naturalized in many places. The following illustration shows fuchsia growing in a hedge in Ireland. Fuchsia is also the name given to the typical color of the flower—although there are cultivated varieties with other colors. Plumier named the fuchsia in honor of the German physician and botanist Leonhard Fuchs (1501–66), who was the first botanist to compile a botanical glossary; he called it Fuchsia triphylla, flore coccineo.

Fuchs was trained as a physician and in the 16th century, when most medicines were herbal, botany was an essential part of the medical curriculum. But Fuchs went further than most medical students. He accepted that while a knowledge of plants was necessary for a physician, the study of plants should be enjoyable in itself. He derived great pleasure from walking through the woods and meadows and observing the great variety of plant life, and he believed that anyone studying plants would delight in learning to recognize and understand them. In 1542 Fuchs published a book about plants. Its title was De historia stirpium commentarii insignes (Notable commentaries on the history of plants). The book appeared first in Basel, Switzerland, and in 1543 it was translated into German, Dutch, and English (its English title was New Herbal).

This book was different from all the herbals that had gone before. It was customary to include illustrations of plants in such a work, but Fuchs believed that the illustrations should be very precise and accurate, so they could be an aid to identification. In the preface to his work he wrote the following.

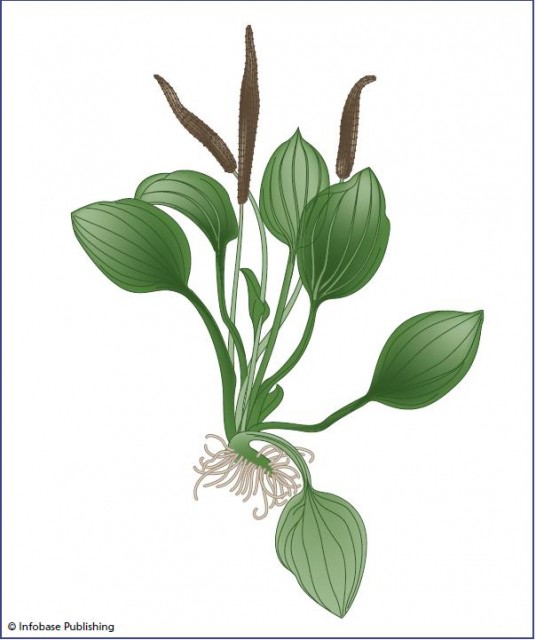

The llustration of common plantain (Plantago major) based on the woodcut in the New Herbal shows how detailed Fuchs insisted the drawings should be, and in order to provide as much botanical information as possible, some of the illustrations showed flowers, fruits, and seeds all on the same plant at the same time. That is a botanical impossibility, but it is a valuable technique for maximizing the utility of the drawing. Fuchs had invented botanical illustration, and he insisted that artists work under his direct supervision to ensure botanical accuracy. Three artists contributed to the work, and the book includes a picture of all three of them working from a plant in a vase. Albrecht Meyer drew the illustrations, Heinrich Fullmaurer transferred Meyer's drawings onto woodblocks, and Veit Rudolf Speckle carved the blocks. There is no use of shading in the drawings, as the illustration of the plantain shows. That is because Fuchs intended the illustrations to be colored and the book appeared in both colored and black-and-white editions.

Fuchs was inspired by an earlier work, the three volumes of Herbarium vivae eicones (Pictures of living herbs) by another German botanist Otto Brunfels (1488–1534) that was published between 1503 and 1506. Brunfels illustrated his herbal with pictures drawn from living plants, some pictures showing withered or insect-damaged flowers and leaves. But Fuchs was more ambitious. The New Herbal, which took him more than 30 years to produce, described approximately 400 wild plants and more than 100 cultivated plants, and it had 512 pictures, many drawn from specimens he had grown in his own garden. The plants were listed alphabetically by their Greek names and they included some New World species that Fuchs was describing for the first time, including corn (Zea mays) and chili pepper (Capsicum species—Fuchs called it siliquastrum—“ big pod”). Not all Fuchs's descriptions were accurate. He

relied on classical authors, especially Dioscorides, but Fuchs had never visited the Mediterranean and sometimes confused characteristics of Mediterranean plants with those of northern European plants, which were not the same. He also listed some species more than once under different names, because of mistaken identification. Nevertheless, his New Herbal was a magnificent achievement.

The New Herbal was written for the benefit of physicians. Fuchs complained that it was difficult to find even one physician in 100 who had accurate knowledge of even a few plants. It was to help them that he included a glossary—perhaps the first—of botanical terms. Leonhard Fuchs was born on January 17, 1501, in Wemding, Bavaria. He was educated at a school in Heilbronn and from the age of 12 at the Marienschule in Erfurt, Thuringia. He qualified as a physician in 1524 at the University of Ingolstadt, Bavaria, and practiced medicine in Munich from 1524 to 1526, when he became professor of medicine at Ingolstadt. In 1528 he became personal physician to Georg, margrave of Brandenburg, remaining in this post until 1531. In 1533 he moved to the University of Tubingen, where he was chancellor several times and for many years professor of medicine. Fuchs remained at Tubingen until his death on May 10, 1566.

- Nicholas Culpeper and His Herbal Best Seller

- John Gerard and His Herbal

- Rembert Dodoens and the First Flemish Herbal

- Conrad Gessner, the German Pliny

- Konrad von Megenberg and His Illustrated Herbal

- Albert the Great and the Structure of Plants

- The Aztec Herbal

- Shennong, the Divine Farmer

- John Ray and His Encyclopedia of Plant Life