Representing Africa II: Exploration, Colonialism, and Imperialism

The earliest European human geographies of Africa were geographies of exploration and conquest, and from the era of the Atlantic slave trade through colonialism (a span of exploitation of Africa stretching from about 1450 into the 1960s and 1970s), they shaped the way much of the world views Africa. Through the Atlantic slave trade, an estimated 11.6 million Africans were forcibly relocated to the Americas, while roughly an equal number are estimated to have died along the way in what has come to be called the Middle Passage. Historical geographers of Africa also point to the massive impacts of the Atlantic slave trade 'within' Africa. Untold millions died in Africa itself as a result of slave raiding, the destruction of babies, the sick, or the elderly that were captured, and still millions more were forcibly displaced within the continent. For example, the route from the southern Congo basin's interior empires of Luba and Lunda to the Portuguese slave port of Luanda came to be known as the Way of Death because of the atrocities all along it. About two thirds of the population of today's Zambia can trace its geographical and cultural lineage to the Luba–Lunda region of Congo, their ancestors having fled the collapse of these empires due to the crushing blow of Portuguese slave raiding and enslavement. British, French, Dutch, Spanish, and eventually American slaving ships expanded upon the Portuguese beginnings of the trade, with their main interests in the Atlantic West African coast. African states, city states, or empires that collaborated with the slave trade expanded the reach of their powers, irreparably corrupting their relations with neighboring peoples, the most likely to fall victim to the slave raiders.

West Africa's fortunes in the period of the slave trade illustrate its lasting geographical impacts. From the eighth to the fifteenth century CE, a set of major empires rose and fell along the Sahelian belt of West Africa, capitalizing on their geographical position to be the middle agents of trade between West Africa's gold rich forest belt and the Arab north (and Europe – the metal for the gold coins of the Italian Renaissance came mostly from West Africa) across the Sahara. The empires of Ghana, Mali, and Songhai, in particular, had highly developed bureaucracies and hierarchies of administration, beautiful architecture, renowned universities, extensive libraries, rigorous legal codes, and immense wealth. When we look at the Sahel today, it is one of the world's poorest regions. This reversal of fortunes symbolizes the impacts that the slave trade, and the later period of formal colonial rule, had on the continent as a whole, and it is a lesson in fundamentals of economic geography.When the Portuguese and other Europeans began to trade along the Atlantic West African coast, they cut out the middle agent role that the Sahelian empires had enjoyed.

By the nineteenth-century, opposition to the Atlantic slave trade, and to slavery in general, had grown quite strong, not only in Europe and the Americas, but also in Africa. Gradually, the slave trade gave way to what was termed the Legitimate Trade – as a tacit acknowledgement of how illegitimate the previous Euro American trade with the continent had been. But the legitimate trade hardly brought an end to Euro American exploitation of Africa – indeed, it accelerated it. Imperial rivalries and competition between European powers for access to and control of Africa's significant store of natural resources and its many market outlets for European manufactured goods gave rise to the era of Geography Militant, when European explorers and geographers embarked on the cause of cataloging the continent's resources, products, and markets for their home countries. Even while agreeing together to avoid selling the most advanced line of weapons to African states, the Europeans competed heavily with one another to set up exclusive trade deals, to redirect the productive forces of African farmers, and, occasionally and in specific settings, to control territories and implant colonists. In South Africa, the implantation of white settlers had begun a bit earlier, with the Dutch establishment of Cape Town in 1652 CE. White settlement intensified in the nineteenth-century, particularly with the 1806 handover of Cape Colony to the British, and then the discoveries of the enormous diamond and gold deposits (in and around Kimberly and Johannesburg, respectively) later in the century. The French conquest of Algeria in 1832 led to French settlement there in relatively modest numbers. Elsewhere, only small white populations existed, chiefly in port cities or in areas of mining or missionary activity, but the Euro American presence became quite strong in other ways – as a controlling hand on trade, as an influence on religious and cultural development.

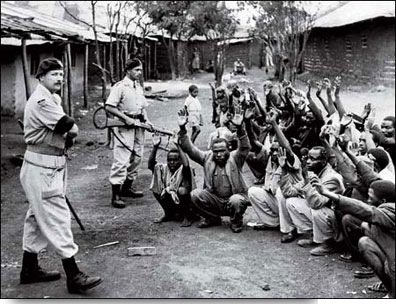

Eventually, the competition between Europeans over African resources and markets led the German ruler, Kaiser Wilhelm, to call for a conference of European powers to settle disputes by marking out spheres of influence. This conference, what we now call the Berlin Conference of 1884–85, did establish these spheres of influence, delineating the rightful claims of the British, French, German, Belgian, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish. However, the fact that few of the spheres claimed were actually even remotely under the control of those who claimed them in Berlin set off the scramble for Africa that lasted until the 1914 outbreak of World War I. In this scramble, the Europeans set about the task of pacifying the territories they had laid claim to. In some areas, the decades from 1880 to 1910 were as a result bloodier and more disastrous for Africans than the four centuries of slave trading. Some 5–10 million people are estimated to have died in the ruthless and shocking Anglo Belgian India Rubber concession area of what Belgian King Leopold II callously called the Congo Free State (after 1908, this became the Belgian Congo, and after 1960, the Democratic Republic of Congo). The Germans nearly wiped out the entire Herero ethnic group of German Southwest Africa (today's Namibia). The Italian conquest of Libya killed a third of its population. Other transitions to formal colonial rule occurred more peaceably, or at least came about in the absence of genocide. In any case, by 1914, nearly all of the continent had fallen under European control. The only politically independent countries by that year were Ethiopia, Liberia, and South Africa. Liberia, though, was a de facto colony of the United States, and more particularly of the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, whose enormous holdings in the territory gave rise to it being mockingly called the Republic of Firestone. South Africa had gained independence in 1910 – but as a white minority ruled state where the black majority were denied political and economic rights, along with Asian immigrants and mixed race peoples.