Republic of Kenya

POPULATION: 44.86 million (2014)

AREA: 224,960 sq. mi. (582, 646 sq. km)

LANGUAGES: English, Swahili (official); Gikuyu, Nandi, Kamba, Luhya, Luo

NATIONAL CURRENCY: Kenya shilling

PRINCIPAL RELIGIONS: Protestant 38%, Roman Catholic 28%, Traditional 26%, Muslim 7%, Other 1%

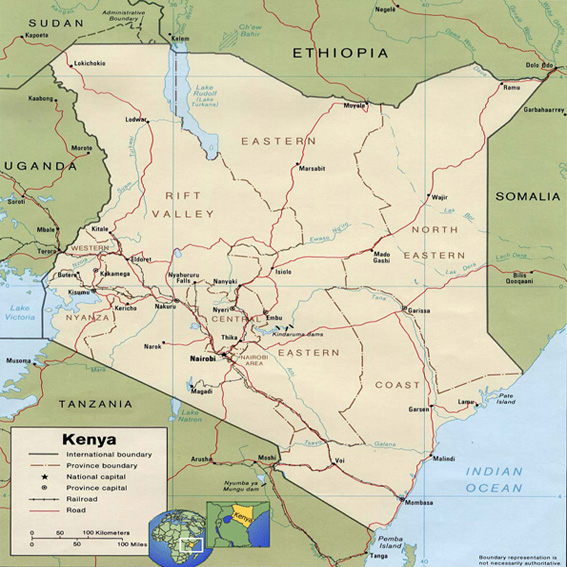

CITIES: Nairobi (capital), 2,000,000 (1999 est.); Mombasa, Nakuru, Kitale, Nyeri, Kisumu, Thika, Malindi, Kericho

ANNUAL RAINFALL: Varies from 29 in. (750 mm) in the highlands and coastal belt to 20 in. (500 mm) for most of the country.

ECONOMY: GDP $60.94 billion (2014)

PRINCIPAL PRODUCTS AND EXPORTS:

- Agricultural: tea, coffee, sugarcane, corn, fruit, dairy, vegetables, beef, pork, poultry, eggs

- Manufacturing: food and agro-processing, textiles, petroleum processing, cement, plastics

- Mining: salt, rubies, gold, limestone, soda ash, garnets

- Tourism: Important to the Kenyan economy. Principal attractions are the nature preserves.

GOVERNMENT: Independence from Great Britain, 1963. Republic with president elected by universal suffrage. Governing body: 200-member National Assembly (legislative body), 188 elected, 12 appointed by the president.

HEADS OF STATE SINCE INDEPENDENCE:

- 1963–1978 Prime Minister Jomo Kenyatta (president after 1964)

- 1978– President Daniel Toroitich arap Moi

ARMED FORCES: 24,200 (1998 est.)

EDUCATION: Free and compulsory for ages 6–14; literacy rate 78%

The nation of Kenya, which lies on the Indian Ocean and straddles the equator, is the commercial center of East Africa. After gaining independence from Britain in 1963, Kenya developed one of the most successful economies in the region. However, since the late 1980s, the nation's prosperity and stability have been hampered by political corruption, ethnic violence, and a rapidly increasing population.

GEOGRAPHY

Kenya's diverse terrain includes five major regions: the coastal plain, the central highlands, the Rift Valley, the western highlands, and the dry plateaus and mountains of the north and northeast. Along the Indian Ocean coast, dense plant life and mangrove trees thrive in the heat and humidity. A long coral reef lies just offshore. Moving inland from the coast, the climate turns drier and the vegetation thins out. The land rises gradually up to the central highlands, which feature high plateaus and mountains. Mount Kenya, the highest point in the country, sits in the heart of the central highlands. The lower slopes of Mount Kenya are green and moist, while the upper slopes are capped with icy glaciers. Home to most of the country's people, the central and southern highlands are covered in rich volcanic soils.

The Rift Valley, a deep north-south trench, separates the central and western highlands. A string of lakes in the valley provide water and fish to local people. West of the Rift Valley lie the western highlands. Although located on the equator, the region is so high that the climate stays fairly cool. Rain falls throughout the year, enriching the fertile soil and making the western highlands a center of Kenyan agriculture. Most other parts of Kenya have two rainy seasons a year that occur unpredictably, resulting in frequent droughts. The driest part of Kenya, the northern region, includes some stretches of desert.

HISTORY

Prior to the arrival of the British in the late 1800s, the peoples of Kenya lived in well-established homelands. The GIKUYU formed stable farming communities in the south. The LUO people around Lake Victoria also farmed. The MAASAI led a nomadic life, herding cattle in the central inland region. Along the coast, traders who spoke SWAHILI established contacts with Arab and Asian merchants. Members of different groups could travel with some freedom between regions. The British changed this situation completely.

Colonization

In 1888 Britain granted a charter to the British East India Company to exploit part of East Africa. However, the British settlers met resistance from the local people. In 1895 Britain began building a railroad from the coastal city of Mombasa to Lake Victoria in the west. The railroad carried British troops and settlers into the interior, speeding up the conquest of the territory. By 1911 Britain had full control.

The British moved the capital inland from Mombasa to NAIROBI and encouraged whites to settle in the interior. The central highlands came to be known as the “White Highlands,” as settlers established large plantations to grow cash crops, including wheat, tea, and coffee.

The colonial rulers treated the indigenous peoples harshly. They took land from Africans and created large white-owned plantations. They forced Africans to live and work on the plantations, either as slaves or as tenant farmers. The British settlers also fenced off much of the land on which the Maasai nomads had grazed their cattle, turning open plains into private property. The Maasai were eventually forced into the dry areas around the Rift Valley. In addition, colonial authorities divided the country into districts and restricted the freedom of Africans to cross district borders. The new borders often separated members of related ethnic groups and disrupted long-standing trade networks.

World War I to Independence

World War I was a disaster for the Gikuyu. The British drafted 150,000 Gikuyu, and nearly one-third of them died on the battlefield. Thousands more perished in a worldwide influenza epidemic in 1919.

Following the war, opposition to British rule grew. Many Kenyans refused to perform labor demanded by the government, and African political groups began to protest colonial policies such as land seizure and wage cuts. For a time Gikuyu political organizations worked with British officials to ease some of these problems. However, in 1929 a serious crisis emerged when Christian missionaries attempted to stop the Gikuyu practice of female circumcision, performing surgery on the sexual organs of girls and women. Up to this time the missionaries had succeeded in converting many Gikuyu to Christianity. However, the dispute led some Gikuyu to abandon the missions and set up their own independent churches.

Meanwhile, white farmers began to take over land in reserves that the British had set aside for Africans. Many Gikuyu and other herding peoples lost land rights. Large numbers of rural people moved to cities such as Nairobi, which soon swelled with the poor and unemployed.

In 1944 a group of educated Africans founded the Kenya African Union (KAU) to demand the return of land taken by settlers. Meanwhile, peasants organized an armed guerrilla group called the MAU MAU. In 1947 Jomo KENYATTA became the head of the KAU. Although he distanced himself from the Mau Mau, the British were convinced that he was secretly behind the armed movement. They arrested and jailed Kenyatta, setting off a bloody war known as the Mau Mau rebellion. Partly a civil war among the Gikuyu and partly a revolt against the British, the conflict lasted from 1952 to 1956. About 13,000 Gikuyu died in the violence.

Following the Mau Mau rebellion, political change came swiftly in Kenya. Africans were allowed to elect an assembly for the first time, and Britain prepared to grant them majority rule. However, in 1959 white guards at a detention camp clubbed 11 prisoners to death. The episode caused a scandal and convinced the British to give up control of Kenya. Africans held free elections in 1961 and chose Kenyatta as the country's prime minister. Kenya achieved full independence two years later, although it remained part of the British Commonwealth, a group of former British colonies that maintain trade and cultural ties with Britain.

Independent Kenya

Jomo Kenyatta became president of the new nation, with the slogan of “Uhuru na Kenyatta” (“independence with Kenyatta”). He made his own party, the Kenya African National Union (KANU), the only political party. Under Kenyatta's rule the Gikuyu enjoyed political and economic control. But in 1966, the vice president, a Luo named Oginga Odinga, resigned to form a new party dominated by the Luo. Three years later, a Luo attacked Kenyatta, who then outlawed Odinga's party.

During this period, high prices for coffee and tea and a booming tourist industry made Kenya one of the most prosperous states in Africa. However, it still lacked political stability. As Kenyatta grew older, KANU split into rival factions over the choice of his successor. When he died in 1978, Vice President Daniel arap MOI assumed the presidency. Moi identified with a new ethnic group called the Kalenjin, partly made up of soldiers who had served in World War II. A year after Moi took office, new elections were held. Moi won by rigging the vote count and blocking Odinga and the Luo party from participating. He then proceeded to break up the Gikuyu control over businesses and farms and give preference to the Kalenjin.

Three years later, members of the air force attempted a coup. The coup failed, and Moi cracked down on his opponents. As he became more autocratic, church leaders urged him to reopen the political system to more than one party. At about the same time, a disastrous drought struck the country and coffee prices fell to an all-time low. International banks suspended loans to Kenya's government. Bowing to pressure at home and abroad, Moi allowed opposition parties to participate in the elections of 1992. But his rivals split into competing ethnic groups, sapping the strength of their opposition to Moi.

With no effective opponents, Moi was reelected with less than 40 percent of the vote. The same ethnic rivalries among his opponents helped Moi to win the 1997 elections.

Moi's presidency has continued to be marked by violence, corruption, and economic decline. He has used his control over the police, army, and media to shape policy. Although he has promised a more “people sensitive” administration in 1997, he has done little to make it a reality.

ECONOMY

Three quarters of Kenya's people work in agriculture, which produces about one third of the country's gross domestic product (GDP). The main export crops are coffee and tea. Other crops include sugarcane, flowers, fruit, vegetables, and sisal—a fiber used in making ropes, mats, and baskets. During the colonial era, white landowners used African laborers to produce coffee and tea on large plantations, but today half of Kenya's coffee is grown on small farms. Coffee is such an important crop in the country that any variation in its world price affects the entire economy.

Kenya's manufacturing industries produce a wide range of products, including textiles, clothing, vehicles, tires, chemicals, steel, minerals, and books. Manufacturing makes up about one fifth of the GDP, but it employs only about 1 percent of the work force. Firms from the United States and Britain control about half of the manufacturing businesses. Kenya's frequent droughts have hurt its industries, which rely heavily on hydroelectric power.

The largest portion of the country's economy is the service industry, which includes trade and tourism. Since the late 1970s, tourism has emerged as a major source of income. Thousands of visitors come each year to game preserves such as Masai Mara, along the border with TANZANIA. However, Kenya's government has not succeeded in protecting and managing its wildlife resources, leading to a decline in the animal populations and a drop in tourism. Political unrest and attacks on visitors have also damaged the tourist industry.

PEOPLE AND CULTURES

Kenya contains about 70 different ethnic groups with individual cultures and dialects. Most of its ethnic groups spill over into neighboring nations.

Major Ethnic Groups

The largest ethnic group is the Gikuyu, a farming people who inhabit the south central part of the country between Nairobi and Mount Kenya. The second largest is the Luo, another agricultural society living along the banks of Lake Victoria. Northern Kenya and the Rift Valley are home to nomadic herding groups, such as the Maasai, and agricultural peoples, such as the Nandi. Just inland from the coast live BANTU-speaking farmers such as the Mijikenda and Pokomo; the Swahili trade and fish along the coast. Kenya's traditional societies were small and organized into clans.

Clan identity was flexible, and people moved freely from one clan to another. In some societies status was based on age. Members of similar age groups went through initiation rituals and some of them eventually became leaders. Many of the clans had close trade relations. When the British arrived, they disrupted the network of clan relations by creating internal boundaries and restricting freedom of movement. They appointed certain African leaders as chiefs who were responsible for collecting taxes, keeping the peace, and supplying labor to the white settlers. Modern Kenya has not developed a strong sense of identity as a nation, partly because of the diversity of its ethnic groups and because colonialism widened the gaps between those groups. As a result, Kenyans still identify strongly with their own peoples, and the country's politics has often played out along ethnic lines. (See also Colonialism in Africa, Ethnic Groups and Identity, Plantation Systems.)