Sir Joseph Banks, Unofficial Director of Kew

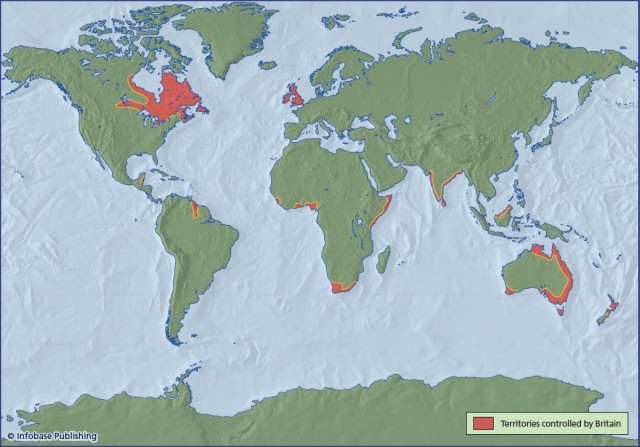

Princess Augusta died in 1772. Her son, George III, inherited both Kew Gardens and Richmond Gardens, and in 1802 he joined them together. George III was keenly interested in agriculture and agricultural research—an enthusiasm that earned him the nickname “Farmer George”—and he turned part of the combined gardens over to raising sheep. During his reign Britain was beginning to industrialize at home and was expanding overseas, while at the same time the country was fighting the Napoleonic Wars. The following map shows the extent of the British Empire in 1822. Although the area of the territories Britain controlled was nowhere near what it would become by the end of the century, nevertheless the colonies were widely scattered geographically and were located in many different climatic zones. Times were changing, and the role of the botanical garden changed with them. Instead of exhibiting exotic plants, Kew Gardens started to conduct serious research, and the naturalist who did most to promote that change was Sir Joseph Banks (1743–1820).

Banks held no official position at Kew, but he was a close friend of the king and shared the king's vision of using the gardens to investigate and develop commercial uses for plants that could benefit the colonies. Banks was highly qualified for this task. He had sailed on several expeditions to collect plants, including the 1768–71 round-the-world voyage of HM Bark Endeavour led by James Cook (1728–79), and in 1778 he was elected president of the Royal Society, a post he held until 1819.

During his time at Kew Gardens, Banks organized expeditions to collect plants in South Africa, Ethiopia, India, China, and Australia, and he arranged for plants to be shipped from the gardens to various colonies. It was Banks who arranged the transfer of breadfruit from Tahiti to the West Indies on HMS Bounty. Banks was so successful that by about 1800 almost every ship sailing to Britain from any British colony carried plants destined for Kew, and when new plants reached Kew the gardeners worked to have them on public display ahead of any other European garden.

Banks was born in London on February 13, 1743. His father, William Banks (1719–61), was a wealthy landowner with an estate in Lincolnshire and a Member of Parliament. Bank entered Harrow School in 1752 at the age of nine, and in 1756 he enrolled at Eton College but was ill after a smallpox inoculation during the 1760 summer vacation and did not return to Eton at its end. Instead he entered Christ Church College, University of Oxford, in December 1760 but left in 1764 without taking a degree. On his father's death in 1761 Banks inherited the Lincolnshire estate and moved to London, dividing his time between London, Oxford, and Lincolnshire. He continued his botanical studies at Chelsea Physic Garden and made friends with many of the leading scientists of the day, including Linnaeus.

He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1766 and in the same year made his first botanical excursion overseas, to Newfoundland and Labrador. His descriptions of the flora and fauna of that region established his scientific reputation and secured his appointment to Cook's Endeavour expedition. In March 1779 Banks married Dorothea Hugesson, and the couple settled in a house in Soho Square, London, where Banks lived for the rest of his life. He was knighted in 1781. In his later years Banks was a trustee of the British Museum. He died in London on June 19, 1820.

- Sir Henry Capel, Princess Augusta, and the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew

- Tulipomania

- Carolus Clusius, the Leiden Botanical Garden, and the Tulip

- Pisa, Padua, and Florence, the First Botanical Gardens

- The Rise of the Herbarium

- Luca Ghini and How to Press Flowers

- Lancelot “Capability” Brown

- Formal Gardens, Restoring Order to a Chaotic World

- Identifying Plants: The Herbal Becomes the Flora