The Somali Democratic Republic

POPULATION: 10.52 million (2014)

AREA: 246,000 sq. mi. (637,660 sq. km)

LANGUAGES: Somali (official); Arabic, Italian, English

NATIONAL CURRENCY: Somali shilling

PRINCIPAL RELIGIONS: Sunni Muslim

CITIES: Mogadishu (capital), 1,219,000 (2001 est.); Hargeisa, Kismayu Merca, Berbera, Boosaaso, Borama, Giamama

ANNUAL RAINFALL: Less than 3 in. (77 mm) overall, but up to 20 in. (550 mm) on high ground

ECONOMY: GDP $5.707 billion (2014)

PRINCIPAL PRODUCTS AND EXPORTS:

- Agricultural: livestock, bananas, incense, sugarcane, cotton, cereals, corn, sorghum, mangoes, beans, fish

- Manufacturing: sugar refining, textiles, limited petroleum refining

- Mining: gypsum; unexploited deposits of uranium, iron ore, bauxite, gold, tin

GOVERNMENT: Independent Somali Republic formed in 1960, the union of British and Italian Somaliland protectorates. Since 1991, the government has been in transition.

HEADS OF STATE SINCE INDEPENDENCE:

- 1960–1967 President Aden Abdullah Osman Daar

- 1967–1969 President Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke

- 1969–1991 Major General Muhammad Siad Barre (president after 1976)

- 1991–1997 Several presidents elected for same period by different groups: Ali Mahdi Mohamed (1991–1997); Abdurahman Ahmed Ali “Tur” (1991–1993); Mohamed Ibrahim Egal (1993– ); Mohammed Farah Aideed

- (1995–1996); Hussein Mohammed Aideed (1996– )

- 1997–2000 41-member National Salvation Council

- 2000– President Abdikassim Salad Hassan

ARMED FORCES: 225,000 (2001 est.)

EDUCATION: Compulsory for ages 6–14; literacy rate 24% (1990 est.)

Since the beginning of its civil war in 1991, Somalia has served as a grisly example of what can happen when an African state collapses. Once a relatively prosperous nation, Somalia turned to ruins when independent warlords—representing various Somali clans—battled viciously for turf and power. The fighting disrupted all services, and famine took thousands of lives. In the year 2000, a peace conference selected a president to head a new central government. But many people still live in areas outside the government's control.

GEOGRAPHY

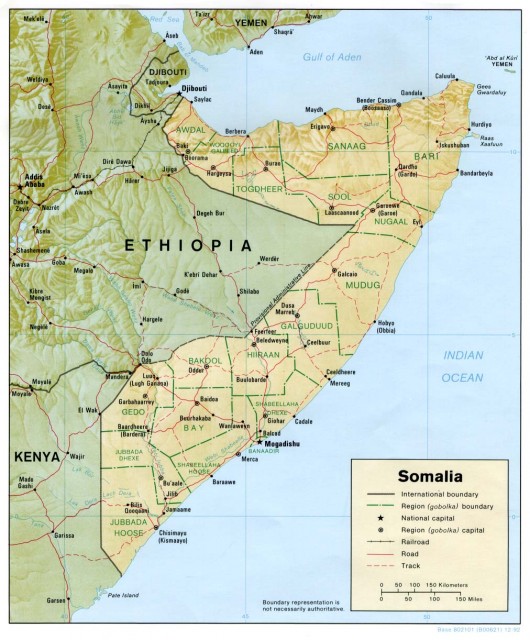

Somalia occupies a strategic position on the Horn of Africa, the region of eastern Africa where the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean meet. The country consists mostly of a large plateau broken by a chain of mountains in the far north. Its extremely hot and dry climate includes two rainy seasons alternating with two dry seasons. During the hottest part of the year, temperatures can climb to over 120°F. Rainfall in the north averages only about 3 inches per year, but the far south of the country can receive up to 20 inches.

Somalia has two rivers that carry water all year round, the Juba and Shabeelle, both in the far south. The area between the rivers is virtually the only place in the country that can support commercial agriculture. Banana and sugar plantations are located here, along with acacia and aloe trees (also grown in the north). Most of the remaining plant life consists of scrub brush and grasses. In the north, such vegetation and the area where it grows are called the guban, meaning “burned.” Mangrove swamps line the coast, which has a cooler and more humid climate than the interior.

The Haud Plateau and the Ogaden Plains, important features of Somalia's geography, stretch out across the nation's northwestern border with ETHIOPIA. Both the Haud and the Ogaden have served as grazing lands for pastoralists for hundreds of years. Until recently, Somalis crossed into Ethiopia on a seasonal basis in search of good pastureland.

However, since the late 1970s this territory has been the subject of disputes between the two countries, and the movement of the herders has been disrupted. Tension over the Haud and Ogaden continues, and even fighting has occurred.

HISTORY AND GOVERNMENT

Ancestors of the Somali peoples inhabited the Horn of Africa as long as 2,000 years ago. Some clans trace their occupation of the area back to the A.D. 1100s. But while the Somalis forged a common culture based on agriculture, pastoralism, and Islam, they never united under a single political ruler.

Colonial Somalia

In the late 1800s, Britain and Italy both established colonies in what is now Somalia. The British occupied the northern region, called Somaliland, but used it mainly as a base to supply their port of Aden on the Arabian Peninsula. British officials allowed the Somalis to keep their local clan councils and left them in charge of resolving conflicts among the local population. However, they transferred the traditional Somali grazing lands of the Haud and Ogaden to Ethiopia. This move laid the groundwork for the later conflicts between the two countries.

The Italians controlled the central and southern regions that make up the bulk of modern Somalia. In Somalia Italiana, colonial officials followed a policy of eliminating local authority and forcing Somalis to adopt Italian law. Southern Somalis reacted to Italian rule with armed resistance that continued until the 1920s.

By the late 1950s, the drive for Somali independence had gained momentum. The most important political parties in both the north and south called for all Somali territories to unite under a single flag. By June 1960, both Somaliland and Somalia Italiana had won independence, and in the following month they joined to form the Somali Republic. Its first elected president was Aden Abdullah Osman Daar.

Civilian Rule

Although united as a nation, the two former colonies remained far apart in many ways. In the north, British colonial policies had produced a highly educated group of Somalis, many of whom attended British universities. In the south, the Italians had provided much less education. The only real tie between the peoples of the two regions was a vague sense of shared identity. When the new state took shape, the south gained most of the benefits of government. The greatest number of political offices went to southerners, even though far more northerners were qualified to fill them.

Northerners and southerners typically had different ideas about what type of policies to pursue. The northern politicians emphasized the importance of developing the nation's economy and fostering good relations with neighboring countries. However, the southerners who dominated the government were generally passionate nationalists.

They pushed for the idea of a “greater Somalia” that incorporated those areas of KENYA and Ethiopia where Somalis lived. This program led to ongoing border clashes with Ethiopia and poor relations with Kenya.

The Barre Regime

On October 15, 1969, Somalia's president Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke was assassinated, and one week later, the military seized control of the government. The leader of the coup was the army's commander in chief, Major General Muhammad Siad Barre.

Along with the other military leaders, Barre formed the Supreme Revolutionary Council to run the country and was selected as the council's chairman. He quickly dismantled Somalia's democratic institutions, banned political parties, and arrested his political opponents. He set up a series of councils, with himself at the head of each, to run the various affairs of state.

Barre moved to eliminate the clan and KINSHIP ties that formed the traditional routes to political power in Somalia. In an effort to unify the nation, his government introduced the first written form of the Somali language and aggressively promoted LITERACY programs. At the same time, Barre signed an agreement with the Soviet Union and established a socialist dictatorship. He also brought most parts of the economy under state control and prohibited private trading activities.

With Soviet help Barre expanded the military. In 1977 he sent Somali troops into Ethiopia to back a rebel group sympathetic to Somali territorial claims. However, this action angered the Soviet Union, which also supported the Ethiopian government. The Soviet Union sent arms and supplies to Ethiopia, and with the help of Cuban troops the Ethiopian army drove the Somalis out. REFUGEES fleeing the fighting poured into Somalia in large numbers. Barre sought assistance from the United States.

By this point Barre had made many enemies. In 1981 northern clans rose against him, and he turned the military against them. The Somali army destroyed the northern city of Hargeisa, killing some 50,000 people. The fighting devastated the northern economy, and civil unrest spread throughout the country. By the late 1980s, several southern clans had established their own militias led by local warlords. In 1990 rebel forces entered the capital of MOGADISHU. Barre fled early the next year.

Civil War and Anarchy

One faction of the United Somali Congress, the group that captured Mogadishu, named General Muhammad Farah Aideed to head the government. However, other groups rejected Aideed, and civil war broke out. Central government in Somalia collapsed entirely. In its place, a dozen or more clans controlled their own regions of the country, supported by their own militias.

Fighting was especially fierce in Mogadishu. The battles destroyed most of the once-beautiful seaside city and created tens of thousands of refugees. A crippling drought struck from 1991 to 1992, creating a famine in which between 300,000 and 500,000 people died. This enormous tragedy led the UNITED NATIONS (UN) and other international agencies to mount an emergency relief operation.

International relief efforts soon gave way to frustration. The UN saw most of its aid taken by the warlords and given to their followers rather than to the starving population. The organization sent troops from several nations—mostly from the United States—to protect the shipments of food, medicine, and other aid. But the operation soon changed its focus to trying to restore peace and order in the country. This ambitious goal meant disarming the warlords, who refused to cooperate. The United States and its allies sought to capture General Aideed. But when Aideed's forces shot down an American helicopter and killed several U.S. troops in a gun battle, the Americans pulled out of the operation. By 1995, the UN had also abandoned relief efforts in Somalia.

While the south was being torn apart by war, the leaders of the northern clans met to discuss the future of their region. In 1991 they decided to secede and form a separate state called Somaliland. Another region called Puntland also declared itself autonomous. Local northern militias turned in their weapons and some order began to return to the north. But so far, other countries have refused to recognize Somaliland as an independent nation, preferring that all of Somalia reunite.

Somalia Today

In 1996 General Aideed was killed in fighting and was succeeded by his son Hussein, who refused to attend peace talks in 1996. Negotiations continued in several countries, but little came of them. Then, in May 2000, President Ismail Omar Guelleh of DJIBOUTI hosted a conference to try to find a solution.

The conference agreed to create an assembly of 245 members, including seats reserved for women and for members of less powerful clans. The assembly chose Abdikassim Salad Hassan as Somalia's new president, to head a government for three years before holding national elections. However, most of the warlords did not take part in the conference, and they remained cool to Salad Hassan's presidency. In addition, Somaliland and Puntland refused to rejoin a united Somali state.

Salad Hassan faces the formidable challenges of restoring peace, disarming the warlords, and rebuilding a nation from the destruction of civil war. The capital lies in ruins and the economy is in tatters. Clan rivalries are as strong as ever. In a more positive development, tensions with Ethiopia have died down, thanks to the diplomatic intervention of Libya's ruler, Muammar al-QADDAFI. But Somalia's road ahead appears long and filled with dangerous obstacles.

ECONOMY

Before the civil war, livestock and agriculture formed the base of Somalia's economy. Livestock was the country's leading export, followed by bananas. Frankincense and myrrh, aromatic gums used in the manufacture of incense and perfume, also provided sources of income. But a series of droughts in the 1980s, combined with the effects of the war, have ravaged Somalia's livestock herds and crippled its agriculture.

The early rulers of independent Somalia tried to develop manufacturing. Between the 1960s and the mid-1970s the country built food processing, textile, and pharmaceutical plants and a petroleum refinery. The economy fared relatively well. But the situation began to deteriorate when the government took over most areas of the economy in the 1970s. Droughts and the ongoing border struggle with Ethiopia made the situation worse.

In the early 1980s Somalia agreed to an economic restructuring plan proposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The program, which included plans to return companies and resources to private ownership, made little headway. In 1984, the economy suffered a severe blow when a cattle disease called rinderpest struck Somali livestock, and Saudi Arabia refused to import any Somali animals. Somalia's exports earnings fell by almost half, and Somalia could no longer make payments on its debts to the IMF. The IMF and other donors cut off aid in 1988, and three years later the civil war began. Since that time, the nation's economy has been in shambles.

PEOPLES AND CULTURES

The Somalis form a single ethnic group related to peoples in the neighboring countries of Ethiopia and Kenya. They traditionally practice a pastoral lifestyle, moving from pasture to pasture with their herds of livestock. However, some Somalis in the more fertile areas of the country have adopted farming.

Most Somalis follow ISLAM, which provides a further cultural connection with peoples in the lands surrounding Somalia. As Muslims, Somali men may have up to four wives, whom they may divorce. The Somalis have long lived in a very decentralized society without hereditary chiefs or kings. Instead, councils of elders run the affairs of the country's six major clan families. Political decisions between clans occur during council meetings, long gatherings in which people discuss matters in great detail before reaching a decision.

Somalia has a distinguished tradition of oral poetry. The Somalis use poetry to preserve history, comment on current events, and express public and personal feelings. The country's first female pop star, Maryam Mursal, turned to poetry to criticize the government of Muhammad Siad Barre. Poetry also plays an important role in the large clan meetings that are the basis of Somali politics.