Consolidation

As with many embryonic fields of study, the work of the pioneers was followed by extensive efforts to consolidate knowledge. A supportive infrastructure of discussion groups and symposia developed first in North America, with the subsequent foundation of newsletters, journals, and edited collections allowing wider dissemination of materials. For example, the first symposium on 'environmental perception and behavior', held at the Annual Meeting of the Association of American Geographers (AAG) at Columbus (Ohio) in April 1965, gave rise to an influential collection of papers. Edited by David Lowenthal, it immediately symptomized the rampant plurality of the field, containing essays on attitudes toward environment, the development of psychological tests to analyze spatial symbolism, human adaptation to Arctic conditions, the study of storm hazards, and the perceptual implications of travel along major urban highways. A further volume, entitled Behavioural Problems in Geography, grew out of the 1968 Annual Meeting of the AAG in Washington, DC. Edited by Kevin Cox and Reginald Golledge, it attempted to bring some measure of overview based around an analytic approach that emphasized theory building and positivist research methodologies.

Individually authored surveys of the state of the art quickly followed. Thomas Saarinen's primer Perception of the Environment, published under the imprimatur of the Association of American Geographers in 1969, offered a simple organizing framework for research findings arranged around spatial scale. His analysis began with personal space – an area of space around the body de fined by culturally observed rules of appropriate interpersonal distance into which intrusion by others is resented and often resisted. The survey then moved up through a spatial hierarchy that extended from the home to the neighborhood, city, region, and nation, culminating in world views. Saarinen also gave expression to the widely held conviction that cognitive behavioralist research could assist practical planning and design by offering critical insight into the relationships between people and their environment.

With hindsight, this text expressed two abiding features of behavioral geography. First, it had a powerful, if seldom recognized, ideological dimension. Behavioral geographers followed spatial analysts in their practice of asserting that the new expert knowledge and associated skills were of great value to society. The basic principle was that cognitive behavioralist research could assist planning and design by offering new understandings and appropriate techniques for studying people's relationships with their environment. In the longer term, however, it became apparent that the results of that research more often revealed evidence of the complex ways in which spaces and places were perceived rather than generating results capable of practical implementation.

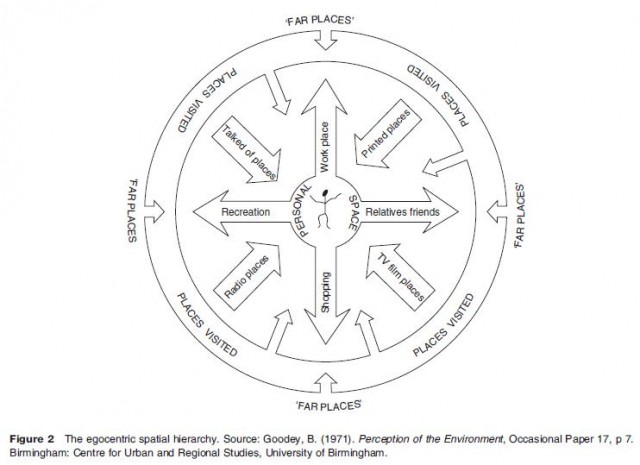

Second, and related, the idea of an egocentric hierarchy of bounded spaces had a compelling appeal. It seemed to offer geographers a lucid way of thinking about the world and implicitly suggested that space was an important variable in environmental cognition. The idea was avidly adopted by other researchers. For example, a 1971 monograph by Brian Goodey suggested a similar hierarchy of perceived spaces as a heuristic device (Figure 2). At its core were personal space and the intimately known places that arouse a sense of belonging. The hierarchy then included places visited with some regularity, places visited less frequently, and extended outwards to 'far places'. There was, however, no direct relationship between distance and knowledge. 'Far places' were often spatially distant but not necessarily so. Furthermore, while individuals may never have visited these places, they could still hold strong views about them on the basis of information derived from other people, from the press or broadcasting, or through the operation of cultural stereotypes.

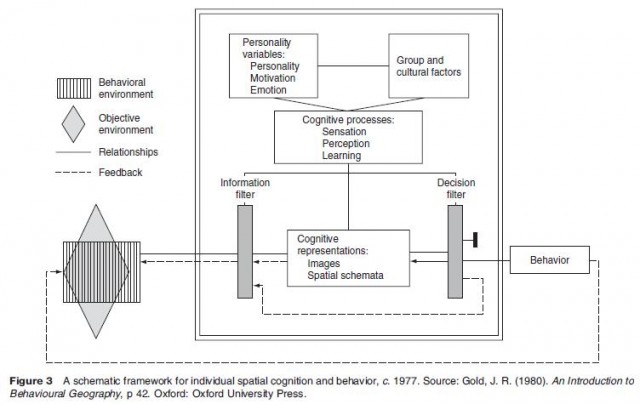

Over time other, more complex frameworks emerged. Figure 3, for example, shows an example dating from around 1977 that purported to identify the elements and relationships linking spatial cognition and behavior. Broadly speaking, it depicts two forms of 'representation' – images and spatial schemata – as the basic cognitive elements that mediate behavior. Individuals are part of two worlds: the objective and behavioral environments. The 'images' that they hold are the mental pictures called to mind when objects, people, places, or areas are not part of current sensory information. 'Spatial schemata' are frameworks within which people organize their knowledge of the environment, containing the residue of past experience and accommodating current sensory information. Both images and spatial schemata are influenced by cognitive processes, personality, and socio cultural variables. These collectively contribute to filters that affect the flow of information and shape the decisions made. Feedback loops at all levels serve to indicate learning, assign value to experience, and to correct future behavioral strategies.

At one level, this type of framework had a seductive simplicity, suggesting permissively broad lines within which to integrate research. Yet despite superficially grafting on terminology and perspectives more closely aligned to the discourse of psychology, in reality such frameworks made only passing reference to established cognitive theory or even to the particular psychological concepts that it included. In retrospect, it now appears as symptomatic of the conceptual weakness that bedevilled behavioral geography. Moreover, this conclusion, which is true for behavioral geography in general, was also true for many of the component areas addressed by researchers in the years up to 1980 – as the following sections indicate.