Theoretical and Conceptual Ideas

The Human Imperative to 'Truck, Barter, and Exchange'

Among many writers who have offered theoretical explanations for the workings of capitalism, the first was Adam Smith, the Scots born philosopher and historian. Largely as a result of his 1776 book, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Smith is regarded as the intellectual father of classical economics. He famously believed in the innate human imperative to 'truck, barter, and exchange' and he developed the theory of the invisible hand of the market. Production and trade take place, argued Smith, in order to secure a profit, and surplus profits are accumulated as capital. Smith said that while people are naturally driven by a selfish desire for gain, ultimately the 'good of society' is better served by the efforts of self interested individuals than it is by altruistic collective action aimed at securing the 'common good'. Best known for his 1798 Essay on the Principle of Population, the political economist Thomas Malthus broadly shared the ideas of Adam Smith. Malthus focused primarily on consumer demand in relation to the finite supply of resources and, in his 1803 Principles of Political Economy, he also argued that the adoption of capitalist approaches in agriculture provided a floor in living standards that was absent in traditional peasant farming economies. Other theorists of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries include David Ricardo, John Say, and John Stuart Mill who each published studies of the workings of capitalist economies. Ricardo's 1817 book, The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, defined fixed capital (e.g., a factory or mill where goods are made) and circulating capital (e.g., raw materials or intermediate products). Together, these types of capital represent one of the four factors of production; the others being land, labor, and entrepreneurship.

The Commercialization Model

Arising from the ideas of Adam Smith and others, the orthodox explanation for the emergence of capitalism – sometimes called the commercialization model – maintains that rational, self interested individuals have been engaging in trade since prehistoric times. If anything, therefore, systems such as feudalism were aberrations rather than the norm. Capitalism (re)emerged as trade became increasingly specialized, technical advances were achieved that yielded improved productivity, and there was an evolving division of labor. Classical economic theory sees the capitalist system as the maturing of long embedded commercial practices and their liberation from political and cultural constraints.

Commodification, the Market, and Comparative Advantage

Commodification is integral to a capitalist system. According to Immanuel Wallerstein, the historical emergence of capitalism involved the ''widespread commodification of processes – not merely exchange processes, but production processes, distribution processes, and investment processes yin the course of seeking to accumulate more and more capital, capitalists have sought to commodify more and more of these social processes in all spheres of economic life''. In short, capitalism involves the commodification of 'everything': all the ingredients in an economic system are capable of being assigned a price and traded.

Markets have, of course, existed throughout human history. The earliest hunting and gathering societies evidently operated a bartering system. However, the introduction of money in antiquity facilitated more sophisticated trade, which then developed its full potential across Europe in the Middle Ages. Trade was highly regulated and restrictions prevented the emergence of truly free markets. A free market, in which all economic decisions regarding transfers of goods, services, and money are made voluntarily, is generally considered to be an essential feature of capitalism. Ideally, individuals trade, bargain, cooperate, and compete in an unfettered and decentralized manner, and the key role of government is not direct intervention or regulation, but simply one of defending market freedoms. Thus, in a capitalist system, the private ownership of property is both acknowledged and legally protected, as is the right of owners to sell their goods and property at a value which they determine. Such an approach is known as laissez faire economics.

Patterns of trade occurring in a free market can reflect a recognition of comparative advantage. The theory of comparative advantage was first propounded by DavidRicardo in 1817 when he demonstrated the idea by examining wine and cloth production in Portugal andEngland. Both commodities could be produced in Portugal more easily than in England. However, the relative cost of production of the two goods also differed within each country. In England, wine production was extremely difficult but cloth could be manufactured more readily. It could therefore be said that there were high opportunity costs for England to produce wine and it was better to focus on cloth making. Although in Portugal it was easy to produce both commodities, there was a comparative advantage in concentrating on the production of a surplus of wine to meet England's demand, and trade it for English surplus cloth. Specialization enabled economies of scale to be secured and investment meant a highquality product could be delivered. England also benefited from the arrangement because, while the cost of its cloth production remained the same, it enjoyed access toa supply of wine produced more cheaply than was possible at home.

Critics point to inherent weaknesses in Ricardo's theory such as its failure to factor in transportation costs and the implied assumption that the advantages of increased production outweigh other problems including environmental impacts and social inequalities. The theory also assumes that capital is immobile. In reality, political restrictions on the flow of capital countered the tendency of entrepreneurs to invest in neither wine nor cloth manufacture in England (where both cost more to produce) and instead to focus their attention only on Portuguese manufacturing. In the absence of such controls, and in situations where the balance of competition is perfect, it is argued that there is a tendency toward absolute advantage whereby one country, or one entity, is able to produce more efficiently than all others.

World-Systems Theory

Wallerstein's world-systems theory has provided a highly influential dynamic structural explanation of the evolving spatial characteristics of the merchant and industrial capitalist world economy. He identifies a core, a periphery and a semi-periphery. Between the 1600s and the late 1800s, regions such as northwest Europe maintained a dominant core position, while others, such as Africa, remained in the periphery. Other regions, for example, the United States, moved from the semi-periphery into the core. In other cases, for example, the Balkan states that had emerged by the nineteenth-century as the Ottoman empire collapsed, the move was from semi-periphery to periphery. Core regions, where wages were consistently higher, technology was more advanced, and production was diversified, exploited both the semi-periphery and the periphery. In peripheral regions, wages were low, technology remained simple, and production was limited in range. Between the two, semi-peripheral regions exhibited a mix of the characteristics of the other two regions and while capable of exploiting the periphery, they were themselves exploited by the core.

The Division of Labor: Entrepreneurs and Proletarianized Wage Earners

A feature of the demise of feudalism, especially in later Medieval England, was the emergence from the smallscale farming peasantry of what some have termed an intermediate stage of agrarian capitalism. Within this stage, two groups may be identified. First, as old feudal laws and customs – under which tenants had once held land from their lord – gradually decayed, they were replaced by economic leases that reflected market conditions. A new lease holding or land owning peasant farmer class was thereby established which was obliged increasingly to respond to market imperatives, to specialize and to produce competitively. Second, those unable to lease or purchase land formed a property less peasantry – a proletariat – that must sell its labor in order to secure a livelihood. The labor that an individualoffered became a commodity that could be precisely evaluated and built into calculations about the costs of production and the price at which products must be sold to yield a profit.

Determining price levels is central to the capitalist system. In a free market, prices depend on the supply of, and demand for, all the means of production (i.e., the resources required for any form of production). In order to maximize profits, entrepreneurial capitalists seek to minimize the costs of production and thereby outcompete other producers. Wages will therefore be subject to downward pressure.

The division of labor, whereby production processes are reduced to a series of simple, repetitive operations, performed by unskilled, low paid workers, offer a means within capitalist systems of lowering production costs. The factory system that developed rapidly in Britain in the eighteenth century was peculiarly well suited to this kind of division of labor. Moreover, in some circumstances, tasks requiring the least skill might be assigned to female labor (one example of the gendered division of labor) or child employees, for whom rates of pay could be set even lower, giving a further opportunity to the owners of capital to secure an enhanced competitive edge in the market.

Marxist Ideas and Interpretations

The notion of the commercialization model at the heart of classical economic theory that the capitalist drive is somehow a natural human trait, and that the emergence of capitalism as the world's dominant socioeconomic system was inevitable, is strongly rejected by several theorists. Most prominent among these is Karl Polanyi whose challenge, articulated in his 1944 book The Great Transformation, to Adam Smith's concept of 'economic man', and his natural tendency to trade and accumulate capital, is very well known. Today's Marxian economists argue that the expansionary drive of capitalism was not a result of an innate human trait, but the product of its own historically specific internal laws of motion. Such critiques depend crucially on the founding body of radical doctrine, commentary, and critical analysis concerning capitalism developed by Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, which the latter articulated in Das Kapital (1867).

Marx regarded capitalism as a mode of production characteristic of a historically specific phase occurring between the decline of feudalism and (what he saw as) the inevitable proletarian revolution that would usher in communism. He argued that the extraction by the bourgeois owners of capital of the surplus value of goods yielded as a result of the efforts of the labor force would ultimately trigger a power struggle in which the laboring classes were bound to prevail. The sequence that Marx predicted depended on his theory of value, which asserts that labor is the sole source of all wealth and profit – an idea which is, however, strongly contested by today's mainstream, and even some Marxian, economists.

Gentlemanly Capitalism

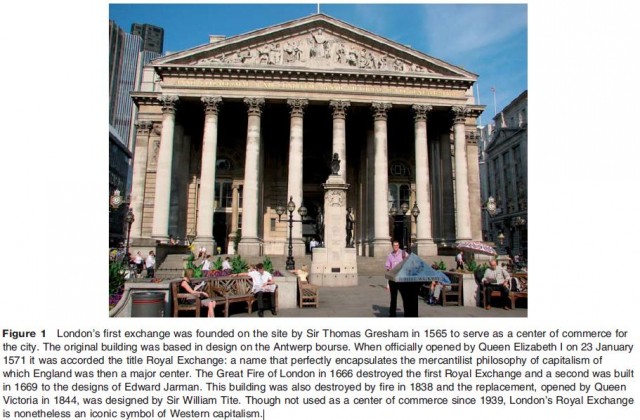

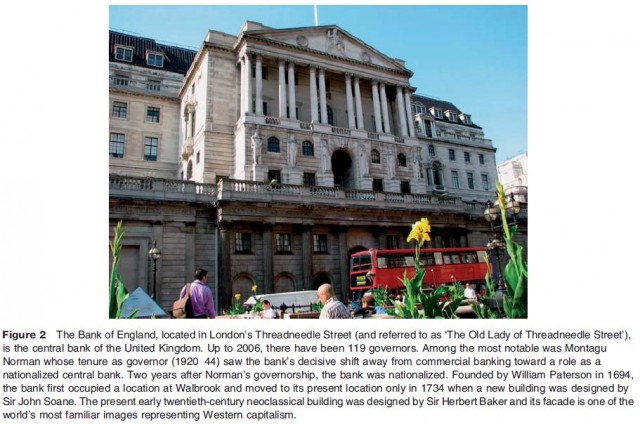

Interconnections between colonialism and imperialism and the development of the capitalist system have attracted considerable academic attention. London and, to a lesser extent, Paris became the preeminent centers of colonial finance, investment, and marketing. The twin iconic symbols of London's dominance were the Royal Exchange (founded in 1565 by Sir Thomas Gresham at the junction of Cornhill and Threadneedle Street) and the Bank of England (set up by Scots born William Paterson in 1694) (Figures 1 and 2). European manufactured goods were traded for primary products and for the output of plantation agriculture such as sugar, cotton,rice, and tobacco. Plantation agriculture depended on slave labor drawn from west Africa. By 1750, as a result of the impetus of capitalism, nearly 4 million Africans had already been taken to the Americas, thereby creating both new colonial economic geographies and a permanent reconfiguration in the cultural geography of two continents.

The notion of gentlemanly capitalism recognizes the pivotal role of economic drivers in European colonialism and imperialism. The term describes the small elite group of influential, London based individuals who managed investment in, and the running of, Britain's colonial economy from the late seventeenth century until the interwar years of the twentieth century. Gentlemanly capitalists controlled the finance and services sector, which are seen as the vital focal point of British imperial power and were the crucial underpinnings that linked the UK with the rest of the globe. Comprising a blend of the old landed elite and the nouveaux riches of the city of London, cemented by marriage connections, oldschool tie links, and later by membership of the same social and sporting clubs, the gentlemanly capitalists exerted immense power and influence across the rest of the world. As a radical revisionist theory of imperialism and capitalism, the thesis has proved highly controversial, but its importance lies in the emphasis it places on finance capitalism as the key motivation for, and determinant of, imperialism.

- Capitalism and Division of Labor

- Toward an Inclusive Geography of Care and Caregiving

- Places and Spaces of Care and Caregiving

- Theorizing and Conceptualizing Care and Caregiving

- Geographies of Care and Caregiving

- Care/Caregiving

- Problems and Limitations of Animation

- Nontemporal Animated Maps

- Temporal Re-Expression, Filtering, and Interpolation