Edward Forbes and the Significance of Ice Ages

The River Tees rises in the northern Pennines—a chain of hills that runs in a north-south direction down the center of northern England—flowing about 70 miles (113 km) to the North Sea. In the upper part of the valley, called Upper Teesdale, there is an unusual community of plants. The plants are not rare, but ordinarily they occur only in arctic or alpine environments very much higher in latitude or elevation than Upper Teesdale. How do they come to be where they are?

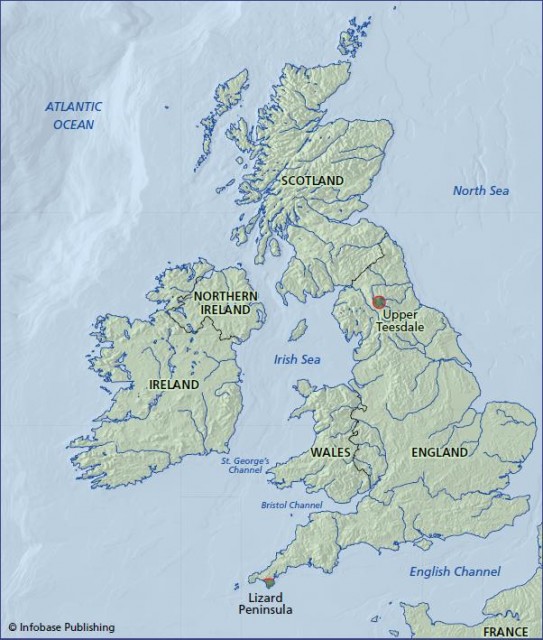

In the far southwest of England a peninsula projects into the ocean. Its most westerly point is called Land's End and its most southerly point—and the most southerly point of mainland Britain— is Lizard Point at the tip of the Lizard Peninsula. On the Lizard Peninsula there is another unusual community of plants. In this case the nearest places with a similar group of plants are in southern and western Ireland, and the plants occur more extensively in Portugal. The map above shows the locations of Upper Teesdale and the Lizard Peninsula. Why are isolated patches of Iberian plants growing in Ireland and southern Britain?

During the first half of the 19th century, Sir Charles Lyell (1797–1875) was a dominant figure in British geology. One of the great geological debates at the time concerned the history of the Earth, on which there were two views. Catastrophists believed the present Earth had been shaped by a series of extremely violent events, while uniformists believed that the Earth had developed through the slow and continual operation of processes that were still taking place. Lyell was a uniformist. He argued that very gradually, over an unimaginably long period, the Earth's surface changed, and as it did so some areas of habitat were destroyed, others greatly modified, and new habitats formed. This, he maintained, allowed species to migrate as widely as they could into new territories, only to become separated from their earlier territories by the appearance of barriers such as mountains and oceans. The barriers were temporary, however, and after millions of years they disappeared as the land was restructured. Lyell did not believe in the evolution of species. He held that each species was created once, in a single event and in a particular place. The distribution of species was therefore to be explained as the result of migrations from certain centers of creation.

Hewett Cottrell Watson (1804–81) was an English botanist with a keen interest in plant distribution. In 1832 he published Outline of Distribution of British Plants, the first of several studies he made of plant distribution in Britain. Watson later divided Great Britain into 112 and Ireland into 40 named areas that he called vice counties, publishing this scheme in 1852 in his book Cybele Britannica. This was the beginning of the compilation of a systematic census of British flora. Watson also observed the way that the composition of plant communities changed with altitude.

Watson described plant communities, but he did not speculate about how they came to be distributed. The Manx geologist Edward Forbes (1815–54) had no such inhibition, however, and combined Watson's vice counties with Lyell's work on Earth history to reach what he believed to be a plausible explanation of distribution. Forbes set out his new theory in 1846, in an essay entitled “On the connexion between the distribution of the existing Fauna and Flora of the British Isles, and the Geological Changes which have affected their Area, especially during the epoch of the Northern Drift,” that appeared in the Memoirs of the Geological Survey of Great Britain. He returned to this theme at the 1854 annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, held in Cambridge, where he delivered a paper “On the geographical distribution of local plants.” Later he delivered a series of six lectures “On the geographical and geological distribution of organized beings” at the Royal Institution in London.

Forbes divided the British Isles into five botanical zones and proposed that the plants and animals inhabiting each of these zones had migrated to them from different regions of continental Europe. The plants of western and southwestern Ireland were related to those in northern Spain, those of southeastern Ireland and southwestern England to plants of the Channel Islands and adjacent France, the plants of southeastern England to those on the opposite side of the English Channel, those on mountains to plants in arctic Scandinavia, and the remainder to those in Germany. Forbes calculated that there had been three distinct periods of migration. An area of land had at one time been exposed in the eastern Atlantic, allowing Iberian plants to migrate northward; at various times the English Channel had disappeared, and land bridges had appeared and disappeared. The mountain flora had drifted southward, carried on icebergs at a time when temperatures were much lower than they were in the 19th century and a large part of northern Europe had been submerged beneath a shallow sea, with the mountains standing above the surface as islands. When the sea level fell and temperatures rose, the plants migrated to higher elevations.

Edward Forbes was born on February 12, 1815, in Douglas, Isle of Man. Natural history fascinated him from an early age, but his health was too delicate for him to attend school until 1828, when he entered Athole House Academy in Douglas as a day pupil. He moved to London in June 1831, intent on becoming an artist, but gave up the idea and returned to Douglas in October. In November he began to study medicine at the University of Edinburgh, but by 1836 he had abandoned any idea of a medical career and instead devoted himself to literature and science. Between 1832, when he examined the plants and animals of the Isle of Man, until 1842, Forbes made a number of field excursions and visits to museums in various parts of Europe. In 1842 he was appointed professor of botany at Kings College London and also as a curator for the Geological Society. In 1844 the Geological Survey appointed him as a paleontologist. He became president of the Geological Society and of the geological section of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1853. In 1854 he was made Regius Professor of Natural History at the University of Edinburgh. Forbes was elected a fellow of the Linnean Society in 1843 and of the Royal Society in 1845. He died after a short illness at Wardie, near Edinburgh, on November 18, 1854.

Forbes came very close to a satisfactory explanation for the distribution of British plants and also for the arctic-alpine plants of Upper Teesdale and the warm-temperate plants of Ireland and the Lizard Peninsula. Paleoclimatologists—scientists who study the ancient history of climate—have discovered that the Upper Teesdale plants are survivors from a period of much colder climate during the most recent ice age. The Irish and Lizard plants are probably survivors from the time when temperatures were rising as the last ice age came to an end. At that time sea levels were much lower than those of today, because of the amount of water held in the ice sheets that covered much of northern Europe and North America. Both the Irish Sea and the English Channel were dry land, and the plants most likely migrated northward from Portugal. It is also possible, but there is no conclusive evidence, that these plant communities have survived even longer, from the period preceding the last ice age.

- Alphonse de Candolle and Why Plants Grow Where They Do

- Franz Meyen and Vegetation Regions

- Karl Ludwig von Willdenow and the Start of Scientific Plant Geography

- Alexander von Humboldt and the Plants of South America

- Ernest Wilson, Collecting in China and Japan

- The Wardian Case

- Robert Fortune, Collecting in Northern China

- George Forrest, Collecting in Yunnan

- Reginald Farrer and Alpine Plants