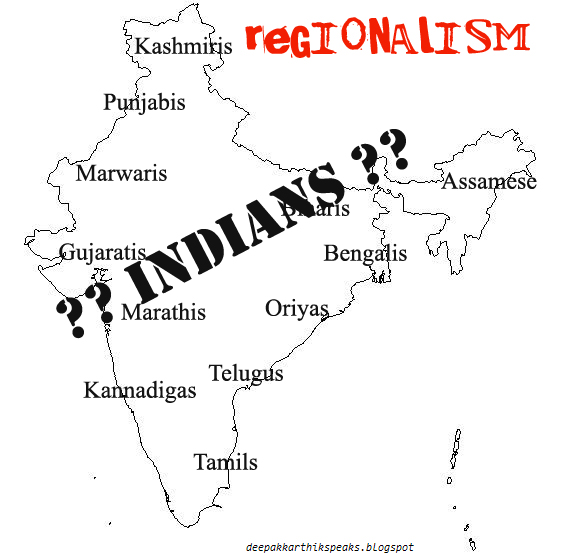

regionalism

REGIONALISM IS A COMPLEX and contested concept. As such, there is no straight or simple answer to what regionalism is. One thing for sure is that regionalism is closely related to REGION. Since a region may connote geographical contiguity ranging from a small neighborhood to a few cities right up to several states and continents, regionalism thus can exist within a state, as parts of states, among states, and between groups of states. But contiguity is not the only variable in delineating regions, which means that regionalism may well occur irrespective of spatial boundaries. It is therefore safe to say that regionalism entails an intricate set of ideas, behaviors, and allegiance in the conscious minds of individuals as to how they perceive their region, hence giving it a distinct physical and cultural feature. The same group of people could be engaged in more than one form of regionalism as regions overlap and change over time. This happens because of the nature of regions as entities that are socially constructed but can also be predefined. Depending on the objective and purpose of the regionalism pursued, some forms would be more elaborated and focused compare to others.

Within a state, regionalism is both positively and negatively correlated with the idea of region. Pessimistically, regionalism can be one manifestation of ethnic nationalism. This could happen in countries where ethnic groups are identified via regions. These groups are normally the minorities and most often than not unfavorably treated or forgotten mainly because there is a lack of integration between the core and the periphery. The problem of assimilation and stark cultural differences are some factors that give rise to the pursuit of regionalist discourses to secure and preserve their beliefs and rights should they perceive the actions of the state as detrimental to their own. Those with higher aspirations and means may set political agendas for separatism and independence. Such activities no doubt challenge the legitimacy and authority of the state. States with many capabilities will try to suppress those aspirations through carrots and sticks, those with fewer capabilities might designate trouble areas as autonomous regions, and those that are incapable may see their territorial boundaries redrawn.

This mostly affects large states, young independent states, politically turmoiled states, and failed states. Some known examples with varying degrees of regionalism are the Chechens in RUSSIA, the Abkhazian and South Ossetian in GEORGIA, the Uyghurs and Tibetans in CHINA, and the Acehian and previous East Timorans in INDONESIA. While ethnicity plays a central role, other factors such as ideology can be a powerful tool for regionalism. Religion and communism, as separate elements or in combination with ethnicity like the predominantly ethnic-Chinese supported communist insurgency in Malaya, could push for the same kind of regionalism.

POSITIVE SIDE

On the positive side, regionalism takes a different form. It may simply reflect the desire of communities that are interested in increasing the efficiencies of their respective towns, counties, or cities through better management and administration. This involves building coalitions that are tailored to specific projects such as land use, housing needs, environmental control, health care, job creation, bioterrorism, traffic improvement, poverty eradication, and others.

Many of these problems cannot be easily handled or solved within the existing political boundaries because of changes in demography and cross-border human activities. As they spill over and become regional issues, interconnectedness then requires local administrations to forge strategic alliances so as to effectively address those concerns. Such regionalism can lead to accountability and better cost utility by leveraging on the competitive advantages of those in alliance. States may also decide to merge towns or cities for similar effects.

The same dynamics could exist for regionalism that transcends parts of bordering states. Mostly centered on economic cooperation, three or more countries may choose to pursue regionalism by earmarking a regional space for development. Geographically adjacent areas are linked to form a distinct space in which differences in the factor endowments (land, labor, capital, etc.) and levels of development are exploited for the purpose of promoting external trade and direct investment. This imaginative space has been given various unofficial terms such as growth triangle, growth quadrangle, transnational economic zone, natural economic territory, circle of growth, extended metropolitan region, or, simply, growth area. Regionalism of this sort is attractive because participating countries are able to gain from the differences in comparative advantage which serve to complement rather than compete with one another. Economic complementarity is not the only motivating factor, as it can also include cooperation on natural resources, infrastructure development, and even tourism. Successful projects can be replicated elsewhere with different modalities of cooperation to meet the local needs and conditions of the region in focus.

Furthermore, a country can participate in several projects at the same time. Such undertakings have the ability to prop up unproductive peripheries by overcoming rigid territorial barriers and utilizing shared experiences.

Some examples are the Indonesia-MALAYSIA–THAILAND growth triangle, the ZAMBIA–MALAWI–MOZAMBIQUE growth triangle, the Tumen River growth area, the Greater Mekong subregion, and the Gulf of Finland growth triangle.

On the other hand, cross-border regionalism could have a negative impact on states. Rather similar to regionalism within states, this may involve the manifestation of ethnic nationalism that goes beyond states' borders. One example is the Kurdish minority located in a region that spans across four countries, including parts of IRAQ, TURKEY, IRAN, and SYRIA. The Kurdish people, while lacking in political unity, have a strong belief and aspiration for independence, but infighting often results in their suppression and repression by the countries they reside in.

Between states, regionalism generally aims at finding regional solutions to regional problems through regional cooperation. A group of neighboring countries with common concerns may decide to gather and commit themselves to dialogue on certain areas of cooperation such as economy, finance, security, health, welfare, cultural, environmental, human rights, and crime. The amount and degree of cooperation varies depending on the problems faced. Security issues could cover terrorism, piracy, and nuclear weapons, while economic issues may focus on trade and investment, and environmental issues would concentrate on pollution, smog, and illegal logging.

INTERDEPENDENCE AND GLOBALIZATION

All these issues cannot be tackled alone, as they are the manifestations of interdependence and globalization. This is where regionalism can be effectively employed to deal with the challenges of globalization. Regionalism allows smaller and weaker states to bind their strengths for better results. States may further decide to establish regional groupings or organizations to institutionalize their cause on matters of importance. Some of the typical regional arrangements are alliances, ententes, free trade areas, and custom unions.

The NORTH AMERICAN FREE TRADE AGREEMENT (NAFTA), for example, was established to enhance regional economic cooperation. So were the Economic Community of West African States and the Mercado Comun del Sur. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was originally an organization concerned with security matters but has since moved to focus on economic regionalism. Groupings with higher ambitions can take regionalism beyond simple cooperation toward integration, as the EUROPEAN UNION did. But regional integration may imply the pooling of sovereignty and interference in state affairs and so directly challenges the state system. Therefore, regionalism between states can have both positive and negative implications and can be seen in stages with political union as the ultimate goal.

The concept of regionalism can be broadened to include cooperation between groups of states. An established regional organization may want to expand its cooperation with countries or regions outside of its own. In East Asia, for example, the Asian financial crisis resulted in a closer relationship between the Southeast Asian region and the Northeast Asian region. Economic and financial regionalism is being pursued under the framework of ASEAN Plus Three. Interregionalism such as the Asia-Europe Meeting, which links East Asia to Europe, is another case in point. What's more is the notion that regionalism as a social construction can occur out of shared common political, economic, or cultural objectives with no bearing to geographical proximity. The Group of Eight and the NORTH ATLANTIC TREATY ORGANIZATION (NATO) are two examples that bring to the table different sets of countries with different purposes but yet are free from any geographic outlay.

REGIONALISM AND REGIONALIZATION

The concepts of regionalism and regionalization are most prevalent in the study of international relations and international political economy. More often than not, these two concepts are used interchangeably to mean the same thing. Differences, however, do exist between them. There are a few interpretations in distinguishing the two concepts.

Regionalism, as a general phenomenon, may refer to a formal project, policy, or scheme promoted by regional states. As a political project, it contains a certain set of ideas, norms, values, principles, and identity that is shared by the participating members. Hence, the characteristics of one regionalist project would obviously be different from another. The aim of such projects varies ranging from promoting a sense of regional awareness to forming supranational institutions.

The process needed to achieve the aim of the project is what can be termed as regionalization. It is an empirical process with an activist element that harmonizes states policies by changing heterogeneous factors defined as obstacles to closer cooperation toward increased coherence and convergence within the given geographical area. Regionalization can also take a different meaning, one that is not tied to a regionalist project. Here, regionalization takes place as the result of spontaneous forces. It depicts a multidimensional and undirected natural process of social and economic interaction driven by the people as nonstate actors that could plausibly contribute to the growth of societal integration and transnational civil society within a regional space. Such vigor may instead give rise to regionalism with the emergence of regional groups and organizations.

Regionalism and regionalization anchored in the economic domain may have a slightly different interpretation. Regionalism can be understood as a political process whereby states cooperate and coordinate their economic policies across regions. One method pursued by states is to form regional trading arrangements. These arrangements furnish states with preferential access to members' markets. Free trade agreement, as it is often called, dates back to the early 1960s but has become an increasing trend in the post-Cold War period marked by a shift from the old protectionist regionalism to the open and flexible new regionalism. But there is still a constant debate as to whether regionalism through trade agreements complements or contradicts the world trading system. Regionalization, on the other hand, is understood as the concentration of regional economic activities and trade flows of market actors. This may involve transnational corporations, entrepreneurs, consumers, investors, and capitalists that have a regional interest.

All these suggest that not only are there differences but the relationship between regionalism and regionalization is progressive and robust. In short, regionalization can both precede and flow from regionalism. One interesting example is the East Asian region, where decades of economic regionalization with the absence of regionalism created an intricate web of interdependence and then saw a postcrisis emergence of regionalism geared toward facilitating further regionalization.