The Republic of Uganda

POPULATION: 37.78 million (2014)

AREA: 93,065 sq. mi. (241,038 sq. km)

LANGUAGES: English (official); over 40 others including Swahili, Ganda, Nyoro, Lango, Acholi, Alur, Chiga, Kenyi, Teso, Arabic

NATIONAL CURRENCY: Uganda shilling

PRINCIPAL RELIGIONS: Christian 66%, Traditional 18%, Muslim 16%

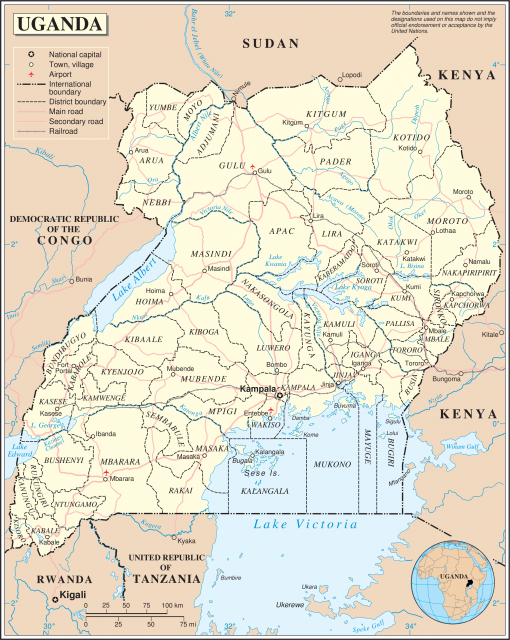

CITIES: Kampala (capital), 1,212,000 (2001 est.); Jinja, Mbale, Mbarara, Masaka, Entebbe, Gulu

ANNUAL RAINFALL: Varies from 90 in. (2,250 mm) near Lake Victoria to 15 in. (400 mm) in the northeast.

ECONOMY: GDP $27.00 billion (2014)

PRINCIPAL PRODUCTS AND EXPORTS:

- Agricultural: coffee, cotton, tea, tobacco, cassava, potatoes, corn, millet, livestock, dairy products

- Manufacturing: sugar, brewing, cotton textiles

- Mining: copper, cobalt

GOVERNMENT: Independence from Britain, 1962. Republic with president elected by universal suffrage. Governing body: National Assembly.

HEADS OF STATE SINCE INDEPENDENCE:

- 1963–1966 President Edward Mutesa II

- 1966–1971 President Milton Obote (prime minister from 1962–1966)

- 1971–1979 President for Life Idi Amin

- 1979–1980 President Yusuf Lule (1979), President Godfrey Binaisa (1979–1980), Paulo Muwanga (1980)

- 1980–1985 President A. Milton Obote

- 1985–1986 General Tito Okello

- 1986– President Yoweri Museveni

ARMED FORCES: 40,000 (2001 est.)

EDUCATION: Free, universal, and compulsory education has not been introduced; literacy rate 62% (1995 est.)

The East African nation of Uganda once served as a symbol of everything that could go wrong in post-independence Africa. Ruled by corrupt dictators and torn by ethnic violence, Uganda was a land of poverty and despair despite its rich natural resources. Since the late 1980s, however, Uganda has made a remarkable turnaround, and many people have looked to it as a model for progress in modern Africa.

GEOGRAPHY

Uganda lies in the Great Lakes region of east-central Africa and shares borders with five other countries: SUDAN to the north, KENYA to the east, TANZANIA and RWANDA to the south, and the CONGO (KINSHASA) to the west.

Located on the equator, the country rests on a high plateau that makes the climate fairly moderate. Much of the country is mountainous, with high peaks rising in the east, west, and southwest. The western end of the Rift Valley, an enormous trench, also passes through Uganda.

Water—rivers, streams, lakes, and swamps—covers about 15 percent of the surface area of Uganda. Among the most prominent bodies of water are Lake Victoria, the world's second-largest freshwater lake, and the NILE RIVER. The Nile begins in Lake Victoria and flows into Lake Albert before traveling more than 3,000 miles north to the Mediterranean Sea.

Uganda enjoys abundant rainfall and very fertile soil, excellent conditions for agriculture. The south and west receive an average of about 90 inches of rain per year. The extreme northeast is much drier, and many people there raise animals rather than plant crops.

HISTORY AND GOVERNMENT

Before the arrival of Europeans in the mid-1800s, Uganda was made up of many autonomous societies. In the north, most people lived in small communities without a strong central authority. In the south, many groups were ruled by chiefs or kings. The largest kingdom was Buganda, on the shores of Lake Victoria in the southern part of Uganda. Muslim traders from the Indian Ocean coast established businesses in Buganda and won influence at the court of the Ganda king.

European Involvement

The first Europeans to visit Uganda were explorers such as John Hanning Speke, who came in 1862 in search of the source of the Nile River. Missionaries arrived about ten years later, and merchants such as Frederick LUGARD of the Imperial British East Africa Company were in the area by 1890. Four years later the British declared a protectorate over the area.

This was a time of turmoil in which Africans fought each other and the British. Christians and Muslims went to war in 1888–1889, and Catholics and Protestants clashed three years later. The kingdom of Bunyoro in the north fought with the British and their allies from the powerful kingdom of Buganda. But the Ganda ruler later rebelled against British authority and took up arms against some of his chiefs, who had converted to Christianity.

The Uganda Agreement

In 1900 the British and representatives of the region's major chiefdoms and kingdoms signed the Uganda Agreement. This document recognized the existence of four separate kingdoms—Buganda, Bunyoro, Toro, and Ankole—within the British colony of Uganda and allowed each state to govern itself. However, Buganda received more autonomy and a larger share of the benefits of colonial development, such as education by Christian missionaries, than the other kingdoms.

A main goal of British rule in Uganda was to exploit the land's fertility. The British put people to work growing crops such as cotton, coffee, and tea to sell as exports. Much of this farming took place in Buganda, as did other economic activity. The British also established their government in this kingdom in a new town called Entebbe, and many Ganda received civil service jobs and helped the British rule the colony.

Development in the south proceeded rapidly, but the British did not establish firm control over the northeast until the late 1920s. Many northerners then moved south to find work, often in the colonial police forces. Some Ganda in the south felt that their privileged position was threatened.

Another source of ethnic tension was the large number of Asian merchants. Asians owned the majority of the sugar plantations, dominated the cotton industry, controlled the manufacturing and importing of most goods, and ran most of the shops in Kampala, the major city that became the capital in 1958. Many indigenous Africans resented the Asians' wealth and power.

The division of Uganda into separate kingdoms produced lasting rivalries. Bunyoro repeatedly pressed to regain the land it lost in its war with Buganda. Meanwhile, the Ganda king demanded independence from the rest of Uganda in an effort to protect Buganda's autonomy.

As political parties formed during the 1950s, religious rivalries reappeared. The Democratic Party was a Catholic stronghold, while the Uganda People's Party had Protestant roots. Local and regional power struggles seemed more important than national unity and independence from Britain. The one thing many Ugandans shared was resentment of the Asian community. A nationwide boycott of non-African businesses in 1954 resulted in many Asians leaving the country when it became independent.

A Difficult New Beginning

In October 1960, Uganda gained independence from Britain and held its first elections the following year. The new constitution called for a single state with little autonomy for individual kingdoms. Buganda rejected this arrangement and refused to participate in the elections. As a result, the Democratic Party won.

The following year a member of the Lango ethnic group named Milton OBOTE joined forces with a Ganda political party. The coalition won the election, with the Ganda king MUTESA II as president and Obote as prime minister. Obote then consolidated his power and pushed aside his Ganda allies. When they tried to stage a coup in 1966, the national army, led by General Idi AMIN DADA, crushed the Ganda and forced Mutesa to flee the country.

During the early years of Obote's reign, Uganda made progress in education, the economy, and other areas. However, Obote abolished all political parties except his own and put many Lango into high government, army, and judicial posts. He turned the country towards socialism and steadily lost support. In 1971 the army revolted, bringing Amin to power.

Uganda Under Idi Amin

At first Idi Amin enjoyed wide popular support. A former national heavyweight boxing champion, he seemed friendly and confident. But beneath his smiles was a cold-blooded and brutal tyrant. Over the next eight years, he plunged Uganda into a world of terror and corruption that claimed perhaps as many as a million lives.

Amin quickly turned against anyone he thought might threaten his control over Uganda and its wealth. In 1972 he expelled all Asians from the country. Most black Ugandans approved of this action, but the country's economy suffered from the loss of these experienced businesspeople. Amin also drove out clergy and missionaries and outlawed some Christian groups. In addition he targeted the Lango and other rival ethnic groups. He did not hesitate to use violence, torture, and murder to advance his goals.

In the end, however, it was Amin's military adventures in other countries, not his reign of terror at home, which led to his downfall. In 1979 he invaded Tanzania to punish its president, Julius NYERERE, for supporting Ugandan rebels. The invasion failed badly, and Tanzanian troops stormed into Kampala and forced Amin to flee to Saudi Arabia. The Movement. Uganda's government was restored with elections.

Obote manipulated the process and regained his position as president. But he could not control ethnic violence in the country, and Ugandans lost patience with his corruption. A rebellion in 1985 pushed him out of office, followed by more than a year of chaos. Finally Yoweri MUSEVENI, the leader of the main rebel group, captured Kampala and proclaimed himself president.

Museveni set about trying to rebuild and unify Uganda. He hoped to overcome the ethnic divisions that had plagued the country for so long, and he argued that political parties increased these rivalries. He therefore outlawed political parties and set up the National Revolutionary Movement, a system of government that claimed to include all Ugandans. Though many feared he would rule as a dictator, Museveni formed a commission to draw up a constitution that would provide fundamental freedoms and protection of HUMAN RIGHTS. The commission spent years consulting people in all parts of Ugandan society, hoping to create a constitution by consensus.

The constitution, adopted in 1995, established a parliament with members elected by the people but forbidden to run as members of a party. The president, also elected, was limited to two terms of five years. The constitution also provided for a vice president, a cabinet of ministers, and independent system of courts.

In 1996 Museveni won Uganda's first free and open presidential election in over 30 years. But the country still faced major problems. Rebel forces in northern and western Uganda, supported by Sudan, fought Museveni's government. Museveni had also involved his country deeply in the civil wars raging in Rwanda and Congo (Kinshasa). His political opponents continued to call for a democracy with political parties. Despite these difficulties, Uganda seemed to recover steadily from the devastating years of Obote and Amin.

In 2001 Museveni won reelection, but his main political opponents refused to participate in the elections and questioned the legitimacy of his victory. Many Ugandans, as well as foreign diplomats, have grown uneasy with Museveni's interventions in Congo and elsewhere. Although the glow of Museveni's early days has faded, many people still hope that he can bring peace and prosperity to Uganda.

ECONOMY

Agriculture is Uganda's main economic activity, employing more than 90 percent of the population and accounting for nearly all of the country's exports. Coffee ranks as the country's most important export. Manufacturing, mining, and the rest of the economy contribute little income. However, tourism has made a strong comeback during the relative calm of the Museveni years. Visitors have long admired Uganda's abundant and varied wildlife and spectacular scenery, including several major national parks.

Museveni's government has improved economic performance by trying to encourage producers to rely less on traditional exports and by selling unprofitable state-owned companies to private investors. New government policies have brought inflation under control, and improved tax collection has increased revenues. The country borrowed heavily from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, which called for many of these changes. In 1998 these institutions recognized Uganda's improving economy and announced a program to forgive some of the country's debt.

PEOPLES AND CULTURES

Several different language families exist in Uganda, providing a foundation for the country's political and ethnic divisions. BANTU speakers dominate the southern portion of the country, where good conditions for agriculture led to the formation of centralized societies that developed into kingdoms. People in the north speak languages of the Eastern Nilotic, Western Nilotic, and Sudanic families. Many northerners raised herds of livestock because the region's climate was too dry for large-scale farming.

All of Uganda's ethnic groups—both northern and southern—are dominated by men. Property and political power pass through the male side of the family, and women are generally treated as socially inferior. The constitution acknowledges this problem by guaranteeing seats in Parliament to women representatives.

About two-thirds of Uganda's people are Christian, while the rest are divided about evenly between ISLAM and traditional African religions. However, most of those who follow Islam or Christianity include traditional beliefs and customs in their worship. In recent years many new religious groups have arisen in Uganda. One of these, the Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments, gained notoriety in 2000 when many of its members committed mass suicide. (See also Colonialism in Africa; Kagwa, Apolo; Tribalism; Wildlife and Game Parks; Women in Africa.)