Chinese-Language Geography

A Long History of Chinese Human Geography

Recognition of Human–Land Relation during the Formative Stage

Human geography started to flourish in China more than 2500 years ago. The concept of 'geography' was first coined in the classic text of Yi Jing (or I Ching, Book of Changes), referring to the observation and understanding of the Earth's surface for the pursuance of human activities. This reflects an early recognition of the human– land relationship, in the language of 'Tian' (the heaven) and 'Di ' (the Earth). The first regional geography text, Yu Gong (Tribute of Yu), was written around 500 BC. Ancient China was divided into nine provinces based on a survey of natural resources. For each province, the boundary, the mountains, the nature of the soil, the waterways, the kinds of products, field tax divisions, the names of tributes, and the minorities were described and the few waterways that provided routes of transporting the tributes were identified. The way China was regionalized implies some kind of administrative division. Besides, the concept of regional disparity, especially with respect to the nature of the soil, is also discernible in the text.

Constituting Part of the Official Historiography

Later, more systematic works in human geography can be found in more official historiographies. These include Shi Ji (The Records of the Grand Historian), written from 109 to 91 BC, by the magnum opus of Sima Qian (145–88 BC) and Han Shu (History of Western Han) by Ban Gu (AD 33–92). The former recounts Chinese history from the mythical Yellow Emperor to the contemporary Emperor Wu of Sima's time. Included in it is a biography, Huozhi Liezhuan (Biography on Goods Multiplication), the theme of which is to developproduction, stimulate prosperity, and raise people's living standards. It represents an early attempt of economic geography and, together with the coverage of the location of cities, their conditions of development, etc., an urban geography text. Han Shu, in contrast, covers the Western Han period only, and includes in it a special appendix, Dili Zhi (The Geographical Gazetteer), which details accounts of the physical landscape, water conservancy, resource extraction, population census, changing territorial boundaries, and tourist resources. This inclusion initiates a new standard of practice in the official historiography of each dynasty. Dili Zhi started to be published independently since the Western Jin Dynasty (AD 265–316). Fang Zhi (local gazetteers) refers to the systematic account of the topography, history, and socioeconomic situation of any local administrative district. Originally restricted to districts of special concern from the point of view of any dynasty, Fang Zhi was later regarded as an essential documentation of each county, prefecture, and province since the tenth century. In the Qing Dynasty (AD 1644 –1911), a special office was even established to coordinate the tasks of writing Fang Zhi, which were also standardized with principles, methods, patterns, and contents. Since its publication, the numbers of Fang Zhi had accumulated to over 10 000 volumes by 1949.

Enriched by Foreign Explorations, Official, and Civil Alike

In addition, there had been many accounts of exploration beyond the Chinese territory undertaken by orders of an emperor or by missionaries and travelers since the early Chinese history. Zhang Qian was ordered thrice (139–119 BC) by the emperor of his time to explore the Mediterraneans for geopolitical considerations. He described the land route across inner Asia and then to the Mediterranean shore, including the ethnic minority regions in the Yunnan–Guizhou plateau. Once the Silk Road was opened, Buddhism spread eastward to China, while many Buddhist monks from China went westward to India to learn more about it. So went, for example, Fa Xian (AD 399–413) and Xuan Zang (AD 627–644). Their publications detail the topography, city defense, transport, agricultural production, climate, people, cultural exchanges, etc., of many places. Besides, other Chinese explorers also went by sea. The most remarkable one is Admiral Zheng He's seven separate expeditions, between 1405 and 1433, to Southeast Asia, Ceylon, the west coast of India, and as far as the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and the east coast of Africa. Although his three books were not as detailed as local gazetteers, they represent valuable additions to the Chinese human geography literature. The last, but not the least, is Xu Xiake, an intellectual not interested in being incorporated by the examination system, who traveled around the country from 1613 to 1639 and systematically recorded all the physical and human geographical phenomena that he observed in his trips.

The Late Penetration of Western Environmental Determinism

The influences on human geography in China also came from the West. Dated back to the Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci's first visit to China in 1528, there had been missionaries from the European Christian churches, bringing along Renaissance informed modern geographic thought. Another wave of interaction with the West came after imperialism from the mid nineteenth-century to the beginning of the twentieth century. During this period, there were more than 100 geographical expeditions and surveys in China led by scholars from Germany, Britain, Sweden, Hungary, France, United States, Russia, and Japan. Some of their works have contributed to the understanding of human geography in China. Besides translations of Western geographical works into Chinese, a means of 'using the advantages of the ''barbarians'' to subdue them', China did send students abroad to study geography (partly under the Boxer Rebellion Indemnity Fund), growing out of the burning desire to employ the more advanced Western technologies to build a stronger nation. The most prominent figures include the Harvard geology doctorate Zhu Kezhen (1890–1974), Edinburgh– Cambridge–Glasgow–trained geologist Ding Wenjiang (1887–1936), and the Leuven geology doctorate Weng Wenhao (1889–1971). (One may add Zhang Shuangwen (1866–1933), who introduced Western geography to China through his command of the Japanese language and, then, translation of the Japanese geography literature.) Given the then dominance of Darwinism and, in turn, environmental determinism, the Chinese were introduced to the Western human–land relationship with Paul Vidal de la Blanche's humanism being a better version of it. In addition, due to their background, advances in human geography were weaker and fewer than those in its physical counterpart. Most of the works on human geography concentrated on the recording and general description of geographical objects. This is especially the case of settlement geography, which resembles Fang Zhi both in methodology and in contents. Seldom were there more theoretical understandings. Nevertheless, due to the strenuous efforts of these scholars, syllabi on geography education were enriched, the professional geography society – the Geographical Society of China – to promote the discipline was founded in 1934 (together with the launching of its journal Acta Geographica Sinica), and the Institute of Geography was established in 1941.

Reinforced by the Soviet Practical Orientation

The Chinese in Yan'an (Yan'an is located on the Loess Plateau in northern Shaanxi province and it was the seat of the Central Committee of the Communist Party from 1937 to 1947) and other liberation areas already had an early taste of the Marxist informed human geography, which approached geographical phenomena from the perspectives of colonialism and unequal development. Most people, however, did not really feel its impacts until the 1950s, when the Soviet influences loomed large in the newly established socialist nation. Unlike in the past, the Soviet influence had been more on the technical means of resolving practical issues than on theoretical and moral geographical knowledge. Before any industrialization program could proceed, knowledge about resources in the prospective region must be made available. There were then nationwide, integrative, regional surveys, spanning geography, geology, climatology, botany, zoology, soil, hydrology, agriculture, forestry, and economy, in which geography played an important role. Influenced by the development within the Soviet geography discipline itself, and propagated by the concept of territorial production systems in particular, human geography in China was dominated by economic geography which, in turn, concentrated on agricultural geography, industrial geography, and transport geography only. As the development strategy was transformed to 'walking on two legs' (industry was emphasized not at the total expense of agriculture) and, later, the Great Leap Forward and its aftermath, so did economic geography shift to focus primarily on agricultural geography in the 1960s and 1970s. The latter contributed to land use planning, agricultural resource assessment, and agricultural regionalization.

Yet, this development in human geography during the first thirty years of socialism should not be interpreted one sidedly; the influences of the Soviets were there for sure, but the Chinese traditional practice did make a difference too. Since the early 1950s, there were mass campaigns, one after another, to purge this or that category of citizens. The intellectuals were purged, while Western texts and ideas were adjudicated. Human geography was no exception to this rule. Between 1950 and 1953, Acta Geographica Sinica published only a few articles on human geography. They were all subject to open and severe criticism. In response, human geographers either converted themselves into physical geographers or merely stopped writing so as to avoid unnecessary scrutiny, harassment and, even worse, purge. This helps explain the comparatively sluggish development of human geography during this period.

Propelled by the Quest for Expansion in Productive Capacity

As the nation sought to recover from the brink of total collapse after the Cultural Revolution and started to recontemplate economic growth again, geography was called into service in the mid 1970s to take stock of resources within the territory. In particular, the Institute of Geography contributed to the large scale surveys of many regions in the country and, especially during the early 1980s, the formulation of master plans for many medium and small sized cities. In 1986, it was even officially announced to subordinate the Institute of Geography under the joint supervision of the China Academy of Sciences and the State Planning Commission. During these ten years, human geographers like Li Xudan emphasized understanding human geography in the context of human–land relations and economic geographer Wu Chuanjun highlighted the consideration of local specificity in territorial development and management. The publication of the specialized journal Economic Geography since 1981 and Human Geography from 1986 marked the diversification as well as resurgence of human geography. These attempts redressed the imbalance of the negligence of local details in public policy in the previous two decades. Concomitantly, besides economic geography, the quest for knowledge about population, natural, and tourist resources is responsible for the establishment as well as promotion of population geography, land resource geography, and tourism geography.

While cities had always played a recipient role in the nation's first thirty years of economic development, they are now considered active agents of growth in themselves as well as for their surrounding countryside. The rapid pace of urbanization alerted the national economic planners to questions like the relationship between the level of urbanization and the level of economic development, rural–urban migration, the urban size hierarchy, and the functional structure, catchment area, and spatial structure of cities. The complexity of the urban question required a more integrated approach to tackle it, leading to the birth of the multidisciplinary urban studies (including economics, sociology, anthropology, politics, history, architecture, and urban planning). The spatial, materialist perspective of geography, as persuasively put forward by Song Jiatai in his argument of the regional foundation of urban development, allowed geographers to dominate the urban discourse at least in the 1980s and 1990s, and so enhanced the subdiscipline urban geography. As urbanization grew even faster, urban geographers started to investigate a whole array of issues such as land assessment, commodity housing, urban redevelopment, suburbanization, the impact of foreign direct investment (FDI), urban governance, world city formation and, even, spatial inequalities. Lately, with the growth of the 'middle class' in the city, there are attempts to explore the issues of mass consumption, culture, and differences. Besides, as intellectual exchanges with the West broaden, urban geographers begin to employ quantitative techniques and other methodologies (such as behavioral and qualitative) in their analyses. (Since it embraced capitalism more warmly as well as being informed by the critique of colonization since the late 1970s, human geography in Taiwan has lately been introduced with some elements of critical geography.)

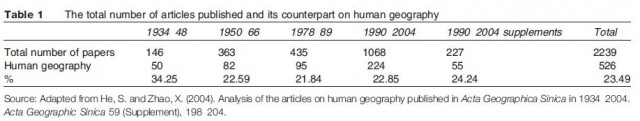

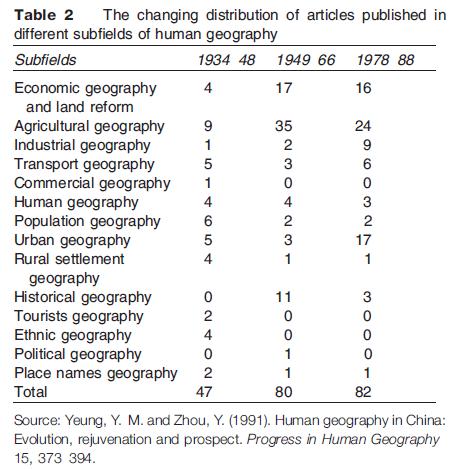

The above description of the development of human geography in China can be supplemented by another reference to the number of papers published in Acta Geographica Sinica for the 70 years between 1934 and 2004 (the journal was not published between 1967 and 1977). Although a total of 2239 papers were published, less than 24% of them could, according to one classification system, be categorized as human geography (Table 1). In other words, human geography had never occupied a more prominent position in the discipline during the contemporary period, especially under socialism. A breakdown of the papers on human geography between 1934 and 1988, as elaborated in Table 2, illustrates that urban geography recently grew faster than other subfields of human geography. (There are some inconsistencies in the total number of papers on human geography between the two tables due to slightly different classification systems.)

Characteristics of Chinese Human Geography

The Dominance of Human in the Human–Land Relation

During the dynastic past, the traditional Chinese culture had made three significant imprints on human geography in China. First, unlike the West, the discipline has a strong human dimension. This is best exemplified in the harmonious 'human–land relation'. According to the oldest Chinese thinking, the nature was the object of veneration. Being dominated by the nature, human activities should follow it. This thinking was soon overtaken by another that emphasized human agency. Having the ability to empower nature just like nature has the ability to influence human activities, people can subdue nature for their own cause. However, informed by the 'human–heaven harmony' cosmology (constituted by both the Confucian and the Daoist components), people, being part of heaven, must realize that there is a limit to the exploitation of nature, beyond which people will suffer from their own deed. Nature and people merely create resonance in each other. That is why people should coexist peacefully with nature. This is a na??ve 'human–land relation', which put humans in the priority, yet underscores the local conditions in implementation. An example of this practice is the widely acclaimed dyke pond system in South China. While the latter undoubtedly exhibits a close harmony between human and nature, one should not neglect the fact that it was organized to enhance humans to produce more resources, including silk and aquatic produces. This is very different from the comparatively more land centered human geography of the West as well as its alleged separation between human beings and nature.

Conceptualization Is Based on Concrete Sense Impressions

The Chinese geographical conceptualization has favored the most concrete sense impressions at the expense of abstract speculation. Very early on in her history, China had already developed a na??ve, but overarching, schema that explains the universe's dynamism in terms of basic forces in the nature, namely the complementary agents of Yin (dark, cold, female, negative) and Yang (light, hot, male, positive), and Wuxing, the five elements or the five phases (water, fire, wood, metal, and earth). Central to the latter are the two interactive cycles of generation (wood feeds fire; fire creates earth (ash); earth bears metal; metal collects water; and water nourishes wood) and restraining (wood parts earth; earth absorbs water; water quenches fire; fire melts metal; and metal chops wood). Most forces in the nature are seen as having the states of Yin and Yang, which are opposite, mutually nonexclusive, interdependent, dynamic, and transformative. Yin and Yang so understood are not discrete duality, as one is interpenetrated into the other. It is the interaction of Yin and Yang that fuels the dynamics of Wuxing. The world, which is constantly changing and full of contradictions, must be understood relationally. To understand and appreciate one state of affairs, it is difficult to exclude its opposite, as what seems to be true now may be the opposite of what it seems to be. These basic forces of Yin, Yang, and Wuxing had in the past been applied to describe interactions and relationships between phenomena, be they seasonal changes, agricultural production, human relationships, or social institutions.

This methodology of understanding human activities favor concrete sense impressions. The custom of understanding nature and society holistically, in particularly from macro to micro and from big to small, builds on sense experience from the struggles in mostly agricultural activities. Comprehending the pattern of any development by senses relies not so much on logic as on literary quotations with profound implicit meanings and lively metaphors to express and understand any object (e.g., the Chinese are fond of using 'the method of painting a dragon and dotting its eye' to convey the message of 'bringing out the salient point'). Dao ('the way') is something to be sensed after cumulative experiences, but not to be explained. Besides, the Yin Yang and Wuxing principle presumes no discrete boundary between an object and its external forces. Everything must be understood in complexity. In particular, the contradictions and their transcendence or integration as implied in Yin and Yang, a type of non Hegelian dialecticism, ensure that any object cannot be understood outside its context. Thus any attempt of de contextualization, such as analyzing the attributes of an object and categorizing it on the basis of its abstracted attributes with great precisions, was discouraged. Concomitantly, there was little discovery of laws that were capable of explaining classes of events. As will be argued in due course, the fact that the Chinese did not institutionally encourage debates also hindered the development of logics, the prerequisite for discovering truth. In fact, it was not necessary for the Chinese geographers to get their hands dirty, as they were equipped to resolve many epistemological issues by the overarching schema at a very early stage of development. In sum, the field of human geography was satisfied with vague, sensual understanding while showing a distaste for analytical explanation of individual phenomena.

Be Practical – For State Governance in Particular

Chinese human geography was practical in orientation and for the pursuance of state governance in particular. Undoubtedly, this was influenced by Dao, 'the way'. The aforementioned characteristics of human orientation and concrete sense impressions encourage Chinese geographers to assign top priority to phenomena that are either closely related to human activities or amenable to human control and reconstruction. This bias becomes comprehensible in the context of the state–society relations. Emperors of different dynasties, sons of heavens, practiced the emperor's way (Huandao). Since the latter intermediated the heaven's way (Tiandao) and human's way (Rendao), the emperors were justified to rule the people on behalf of the heaven. They, therefore, had an absolute authority over their subordinates, not only their right to live or die but also their right to cultural life. Whenever there was a debate among competing arguments or thinking, the power of arbitration, or even adjudication, also rested with the emperors. Since Confucian times, then, intellectuals in China had understood their limited roles in the society, not so much pursuing the truth as elaborating policies and devising techniques of implementation for state governance, and recognized the danger of claiming even a low intellectual autonomy. As the intellectuals put this mentality into practice, Dao that concerns less with the discovery of truth than with the finding of guidance to live in the world was reinforced. Obviously, the geographers could pay attention to nothing but practical issues.

The major concern of the Chinese, dated back to the ancient time, has been state building. To one's surprise, China in the dynastic past had been less unified than a casual historiography would have us believe. Geographically, China was basically divided into three big cultural regions: agriculture in the central, lower regions; animal grazing in the northwest, plateau regions; and fishing and hunting in the northeast, mountainous regions. It was the interaction of these three cultural groups over time, sometimes in war and the concomitant breakup, and sometimes in peace and then coexistence, that had written and rewritten the long Chinese history. During many periods, as mostly before the Song dynasty (i.e., before tenth century), there were boundaries rather than borders due to incessant fighting among competing kingdoms. The country was basically a class divided society in that the political elite was separated from the rest of society, the town from the countryside, and the center from the periphery. The emperor was interested in maintaining political stability by extending his control, usually with some degree of autonomy, to the periphery via the establishment of the local administrative system of counties. In other periods, as between Song and early Qing dynasties (i.e., from tenth to late nineteenth-century), there were more or less clearly defined territories. One saw the increasing centralization of arm forces, but due to regionalization of the socioeconomy, localism grew and local resistance ensued. Therefore, it was still difficult for the state to carry out effective surveillance of the population in every corner of the country. Still in other periods, as from late Qing dynasty to the estab lishment of the People's Republic of China, the territory was identified and recognized by other nation states in the world. Besides mobilization of the means of production for industrialism, there was the centralization of not only means of military violence but also surveillance. The population started to be more vulnerable to state control. Yet, due to the incessant challenge from foreign powers and the fractionalization of internal political coherence, the development of the nation state had not really been completed. The above has shown that China, from the ancient time to the establishment of the socialist nation, had a long history of extending the state power over the territory and its population. At any time, it was imperative for the emperor or any group leader to make sense of one's situation and formulate strategies so as to unify the country. This reliance on practical knowledge for the secular end of governing is best captured in the oft cited slogan since the end of the nineteenth-century: ''To revitalize the nation by science and education'' (Kejiao Xingguo).

This emphasis has directed the discipline of geography to concerns that are one way or other related to state building. Practical knowledge about dynastic politics and the daily life of people was emphasized at the expense of the natural processes underlying the formation of the earth's surface. Chinese geographers were long interested in the ownership and administrative division of land surface. The concerns of Yu Gong fall exactly into these domains. Cartographic production in the past dwelled on fine details of location for administrative control including mountain ranges, river drainages, major towns, strategic defense posts, roads, and traffic. The contents of Fang Zhi consist of various issues of administrative control, from types and quantities of agricultural produce, the amount of arable land, economic situation, designation of cities and towns, local taxes, to administrative division. Besides, the Chinese geographers were interested in the practical knowledge about people's daily life. The practical interest in agricultural production has induced them to research into the relations between the climatic and hydrological conditions, on the one hand, and, on the other, sowing seeds, growth, and harvest of agricultural produces.

While the traditional Chinese culture was instrumental in the development of human geography in the dynastic past, the imperative of the nation state is decisive under socialism (and, to some extent, during the first few decades of the twentieth century too). The socialist state has managed to put its population under surveillance. This measure is implemented together with the centralization of capital and land for industrialization. On the one hand, the quest for order across the territory requires desperately practical knowledge not only about the availability of all means of production – the types, quantities, quality, and location – but also the possibility of combining them across space and over time. The magnitude and complexity of geographical knowledge so required differ from those of the dynastic past. On the other, the intimacy between the state and the society reduces further intellectual autonomy. Knowledge production is under state surveillance in two related ways. The state and its local agencies 'order' the production of knowledge by researchers, whom they directly employ. As a matter of fact, as aforementioned, the Institute of Geography was regrouped under the auspice of the State Planning Commission in 1986. On top of this, there were occasional campaigns to purge the researchers, ensuring that they are under some kind of control. Undoubtedly, things have improved these days, but the quantitative changes have not led to any qualitative changes. As a result, the drive for truth is practically difficult. The fact that the slogan of calling researchers to contribute geographical knowledge to the promotion of a harmonious society by adopting the scientific development worldview was chanted in one of the recent party committee meetings is a testimony to this argument. Examples of reducing the more academic subjects of various subdisciplines to corresponding practical knowledge abound: tourism geography becomes tourist development planning and management; population geography becomes population census and planning control; economic geography becomes economic distribution and development planning; etc. In other words, the three characteristics of human geography in the dynastic past – human , sense , and practical oriented – could also be found under socialism, even attaining higher degree of maturity.

- The Persistence of the State in Chinese Urbanism

- Multiplex Urbanism in the Reform Era

- Socialist Urbanism (1949–1978)

- The Arrival of the West and Modernist Urbanism (1840–1949)

- Administrative and Commercial Urbanism (770 BC–AD 1840)

- Neolithic Settlements and Incipient Urbanism (c. 5000–770 BC)

- Chinese Urbanism

- Critiques and Challenges

- Children’s Experiences of Place