Kalahari Desert: Southern Africa

Odds are, human beings hit upon the lifestyle and innovations that enabled them to populate the planet in some place very like the Kalahari Desert, a small, surprisingly diverse, just-barely desert in southern Africa that still harbors what many geneticists consider the original human beings. The 100,000-square-mile (260,000 sq km) Kalahari is a faint echo of the vast Sahara Desert. The Kalahari is a desert for two reasons. First, it is just as far south of the equator as the Sahara is north, which means that it is a Southern Hemisphere desert for the same reason that the Sahara is a Northern Hemisphere desert and subject to the same drying, descending winds. Second, the Kalahari sits on a plateau about 3,000 feet above sea level and is bounded by mountains to the north and south, which cast a long rain shadow.

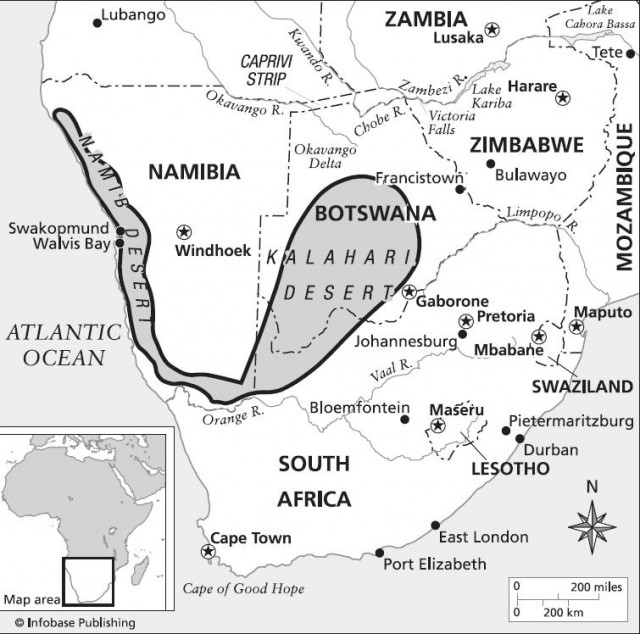

The Kalahari occupies central and southwestern Botswana, part of west central South Africa and part of eastern Namibia. It is part of a vast 360,000-square-mile (930,000 sq km) sand basin that stretches into Angola and Zambia in the north and takes in much of South Africa and Namibia. This larger region has great dune fields that have been frozen into place by a covering of plants, which indicates that it is part of a fossil desert. At some point it converted from true desert to arid grasslands as a result of climate shifts. A Southern Hemisphere desert with seasons reversed from the Northern Hemisphere, temperatures range from 95 to 113°F (35–45°C) in the hot months from October to March and often drop below freezing in the winter months of June to August.

The Kalahari Desert has a pronounced rainy season at the north end, but dries out into a true desert toward the south. Its flat, rolling topography, life-giving rainy season, great expanses of grass, varied vegetation, and sharp climate difference between north and south make the Kalahari one of the richest of desert habitats, rivaled only by North America's Sonoran Desert. This ecological variety might also account for the crucial role the region has played in human evolution.

For at least 30,000 years, the San, or Bushmen as they call themselves, have occupied this demanding landscape. Geneticists attempting to reconstruct human evolution believe that the Bushmen may represent the original human stock, since all other human groups show a genetic connection to the Bushmen that suggests all those other groups have evolved away from these founders of the human line. The genetic evidence suggests that sometime in the last 100,000 years, human beings moved out of Africa and populated the planet. The ancestors of the Bushmen who remained behind in Africa therefore represent the original genetic stock, since they remained isolated in the Kalahari with only minimal genetic mixing with other groups. Moreover, the Kalahari Kung San Bushmen developed a remarkably stable culture that adapted to the hard conditions of their desert-savannah environment through an intimate knowledge of the land rather than technology.

The rich assemblage of other creatures that take advantage of the climatic and ecological diversity of the Kalahari might also provide insight into how human beings developed an adaptable culture that made it possible for people to spread out of Africa and make a living on every continent. The difference between the north and south and the bounty of the wet season in the north prompts great migrations of an array of animals, including elephants, antelope, giraffes, warthogs, hyenas, jackals, lions, bat-eared foxes, and even the rare wild dog, perhaps the ancestor of all domesticated dogs.

This diversity makes the Kalahari Desert essential to understanding the evolution of human beings and our relationship to the land and to other creatures. Moreover, the Kalahari is in the midst of wrenching ecological changes that stem directly from human activities—which makes it both the nursery of the human species and now a test of humanity's maturity.