Rhododendrons, Primulas, and Frank Kingdon-Ward

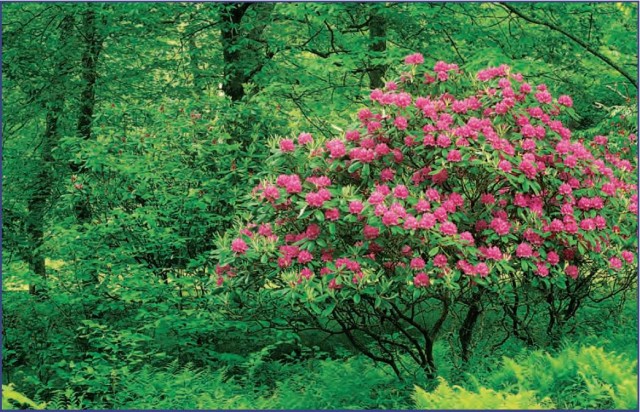

Rhododendrons have long been popular with gardeners. There are approximately 850 species in the genus Rhododendron. At least 26 species occur naturally in North America. The following illustration shows one of these, Catawba rhododendron (R. catawbiense). In China there are about 650 species and large numbers grow in the mountains of Nepal, Bhutan, and Sikkim. The mountains of New Guinea have about 150 species that are found nowhere else.

With so many species, rhododendrons come in a variety of forms. Some are evergreen, some deciduous, most are shrubs or trees but some are climbers, and all of them are poisonous—with some species, honey made from the flowers is also poisonous. They grow in mountainous regions, which means that despite being tropical plants they prefer cool temperatures and high rainfall, requirements that make them ideally suited for cultivation in temperate regions.

Rhododendrons and azaleas, which are hybrid rhododendrons, produce large, showy flowers, and Japanese growers were producing hybrids in the 17th century. Wealthy European landowners also began cultivating them in the 17th century. The first rhododendron in Britain was introduced in 1656. This was the alpine rose (Rhododendron hirsutum), native to the Alps, which had been named by Clusius. Another rhododendron called the alpine rose, R. ferrugineum, was introduced to Britain in 1752. Several North American species were also taken to Britain in the 18th century. Rhododendrons are now cultivated wherever the soil is suitable. At least 500 species have been introduced in Britain and R. ponticum, a Mediterranean species imported from Gibraltar, has escaped cultivation and become a highly invasive weed.

The demand for these ornamental plants made it profitable for botanical expeditions to collect them. Sir Joseph Hooker, director of Kew Gardens, returned to Britain with 45 new species he had found in Sikkim. In 1854 and 1855, Robert Fortune discovered R. ovatum and R. fortunei. These became the source of a series of hybrids that are widely grown in the United States. Between them, George Forrest and Ernest Wilson returned hundreds of species to Europe.

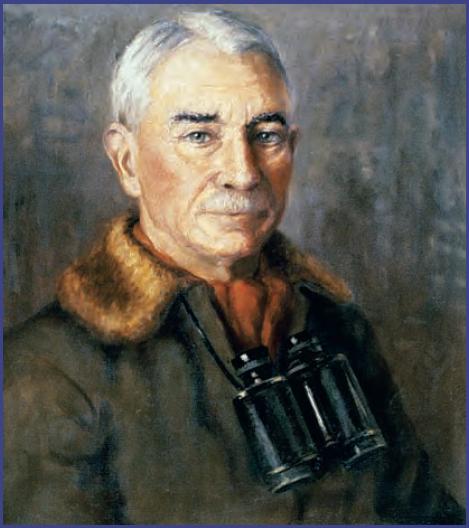

Frank Kingdon-Ward (1885–1958), a botanist and the son of Harry Marshall Ward, a professor of botany, devoted his life to hunting plants in Asia, and his favorite plants were rhododendrons, primulas, and gentians. He made a total of 25 expeditions and discovered 10 species of rhododendrons and two previously unknown primulas in Assam, as well as many other plants. R. wardii, one of the rhododendrons he found, has yellow flowers, and the primulas included the giant primrose (Primula florindae). He wrote 25 books describing his travels and his many adventures. The illustration at right shows him in later life.

Francis Kingdon Ward (at first there was no hyphen and his middle name was his mother's maiden name) was born on November 6, 1885, in Manchester, where his father was professor of botany at Owen College. In 1895 Frank's father became professor of botany at the University of Cambridge. Kingdon-Ward was educated at St. Paul's School in London, and in 1904 he entered Christ's College, Cambridge. His father died in 1906, however, compelling Frank to cut short his education and seek paid employment, but he obtained a degree after two years and agreed to complete his third year later. A friend found him a job teaching in a school in Singapore. He spent two years there before joining a zoological expedition looking for new species along the Yangtze River. He sent a small number of plants back to Cambridge, as well as discovering two previously unknown species of shrew and one new mouse. In 1910 he published an account of his experiences in his book On the Road to Tibet, and the following year he was elected a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and commissioned by a seed company to explore Tibet and Yunnan Province of China looking for hardy plants that would grow in British gardens. Kingdon-Ward collected about 200 specimens, including 22 plants that were new to science, and, as he did from all of his expeditions, he sent a proportion of his finds to the herbarium at Kew Gardens. One of his discoveries was the blue poppy (Meconopsis speciosa). Unfortunately, this would not grow in Britain, where the cultivated Himalayan blue poppy is M. betonicifolia, a different species, but it gave him the title for his next book, published in 1913—The Land of the Blue Poppy. His next expedition took him back to Yunnan and Tibet. In 1914 Kingdon-Ward was in Myanmar (Burma) when World War I began. He enlisted in the army, returning to Myanmar as soon as the war ended.

Kingdon-Ward returned to both Myanmar and Tibet several times over the following years. He visited the United States in 1939, but returned to Britain in time to volunteer for service in World War II. Too old for active service, he was initially employed as a censor and translator of Chinese and other Asian languages. Later, posing as a botanist working for the government, he was sent to Myanmar to search for a route between India and China. He ended the war as an instructor, training airmen in jungle survival. Toward the end of 1947 he and his second wife embarked on an expedition to Manipur, India, collecting herbarium specimens of about 1,000 plant species. There were further expeditions to the border between Assam and Tibet on behalf of the New York Botanical Garden and the Royal Horticultural Society, where the couple collected 37 species of rhododendron and nearly 100 other species. His last expedition, in 1956, was again to Myanmar.

Kingdon-Ward married twice, to Florinda Norman-Thompson in 1923 and to Jean Macklin in 1947; his first marriage ending in divorce. In the course of his travels he suffered many injuries and caught malaria, which recurred at intervals. He suffered a stroke in 1958, from which he died on April 8 without regaining consciousness.

- Adolf Engler and the Vegetation of the World

- Augustin de Candolle and Natural Classification

- How Plants Are Classified

- Carolus Linnaeus and the Binomial System

- Joseph Pitton de Tournefort and the Grouping of Plants

- Jose Mutis and the Bogota Botanical Garden

- Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and the Royal Garden, Paris

- Sir William Hooker, the First Official Director

- Sir Joseph Banks, Unofficial Director of Kew