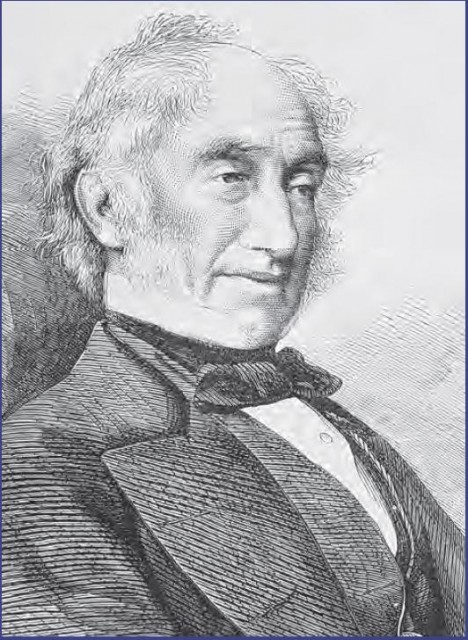

Sir William Hooker, the First Official Director

Both Joseph Banks and George III died in 1820, and in the years following their deaths interest in the gardens waned and they came close to being abandoned. The new king, George IV (1762–1830), had little interest in them. The decline was arrested with the arrival of the first director, Sir William Hooker (1785–1865), in 1841. The following illustration shows Hooker at about this time. Banks had recruited a number of young botanists as plant collectors.

One of them was his protege William Hooker, who had been elected a fellow of the Linnean Society in 1806 at the age of 21. Banks sponsored Hooker for an all-expenses-paid expedition to Iceland in 1809. Unfortunately, the ship caught fire on the return journey and all of Hooker's notes and specimens were destroyed. Banks offered him the unpublished notes from his own 1722 expedition, but Hooker's memory was excellent and he was able to write a full report, Journal of a Tour in Iceland in the Summer of 1809. This established his scientific reputation, and in 1812 Hooker was elected a fellow of the Royal Society. Later, Banks invited Hooker to collect plants in Java, but Hooker declined. This did not affect the friendship between the two men, and in 1820 Banks helped Hooker to obtain the post of Regius Professor of Botany at the University of Glasgow, a position he held until he moved to Kew in 1841. He was a popular lecturer and as well as his teaching and research commitments he established the Royal Botanic Institution of Glasgow and Glasgow Botanic Garden.

William Jackson Hooker was born in Norwich on July 6, 1785, into a wealthy family. He was educated at a school in Norwich, and after leaving school he devoted himself to travel and to studying natural history, at first with a special interest in ornithology and entomology, but turning later to botany. Hooker spent most of 1814 on botanical excursions through France, Switzerland, and northern Italy. He married in 1815 and settled at Halesworth, a small town in Suffolk, where he developed a large herbarium that acquired an international reputation.

An authority on cryptogams—plants that reproduce by spores rather than seeds, including algae, lichens, mosses, and ferns—in 1818 Hooker published Muscologia Britannica, which was an account of all the mosses of Great Britain and Ireland. Between 1818 and 1820, he followed this with Musci exotici (Exotic mosses), published in two volumes, describing non-British mosses and other cryptogams. Among his many other publications, Hooker also compiled Flora Scotica, published in 1821, British Flora (1830), and the five-volume Species Filicum (Species of ferns) between 1846 and 1864. At Kew, Hooker's principal contribution was the renovation of the buildings, redesign of the landscape, and the establishment of the herbarium. Hooker died from a throat infection on August 12, 1865.

William Hooker's son, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817–1911), attended his father's lectures at Glasgow from the age of seven. He was educated at Glasgow High School and graduated in medicine from Glasgow University in 1839. His medical qualification allowed Hooker to sail to the south magnetic pole as assistant ship's surgeon on HMS Erebus as part of the expedition led by Sir James Clark Ross (1800–62). He succeeded his father as director at Kew. Joseph Hooker was director from 1865 to 1885. He continued to develop the landscape of the gardens and supervised the building of the Temperate House. His most important contribution, however, was probably the restoration of the links with British overseas territories that had weakened since they were first established by Sir Joseph Banks. Hooker guided the development of the rubber plantations of Malaysia and India and the introduction of Liberian coffee to Sri Lanka.

- Sir Joseph Banks, Unofficial Director of Kew

- Sir Henry Capel, Princess Augusta, and the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew

- Tulipomania

- Carolus Clusius, the Leiden Botanical Garden, and the Tulip

- Pisa, Padua, and Florence, the First Botanical Gardens

- The Rise of the Herbarium

- Luca Ghini and How to Press Flowers

- Lancelot “Capability” Brown

- Formal Gardens, Restoring Order to a Chaotic World