Government and Politics

hile has a democratic government that allows every adult the right to vote. Its laws apply to everyone. Its citizens have the right to receive fair trials, and they can meet and discuss freely their political and religious beliefs. As a democratic government, the nation educates its citizens, which enables them to make informed decisions about political issues. Chileans' present freedom evolved through a series of constitutions.

The country has had three constitutions. The first two charters, the Constitutions of 1833 and 1891, created republican governments. Citizens of a republic elect politicians to represent them in government. These early governments, however, were by no means democratic. They only protected the rights and privileges of the wealthy aristocracy. What is more, only literate males could vote and run for office. In addition to women, this requirement excluded the majority of male members of early Chilean society.

The Constitution of 1925 was more democratic. The charter gave people from all levels of society the right to vote and participate in government. Initially, the document allowed only men who could read and write the right to vote, but amendments eventually opened voting booths and public service to women and illiterate people as well. The charter also modeled Chile's government after that of the United States. It was divided into three branches with checks and balances to ensure that a few individuals could not take control of the government. The Constitution of 1981 and later amendments gave rise to Chile's present government.

STABILITY OF EARLY REPUBLICAN GOVERNMENTS (1833-1925)

Although they were undemocratic, the Constitutions of 1833 and 1891 established the most durable governments in Latin America from 1833 to 1925. The Chilean people followed the rule of constitutional law. Neither violence nor revolution forced a single Chilean president out of office during this period. Presidents took one another's place by electoral means. No other country in Latin America had such a lengthy record of stability. Most of them had governments similar to Chile's, but civil wars typically cut short presidencies after a few years.

Historians have long questioned why Chile's early governments did not give way to civil war like other Latin American governments did. Scholars point to several interrelated factors that prolonged the existence of Chile's governments. First, Chile's earliest area of settlement—middle Chile—had a homogeneous (of the same kind) Spanish and Spanish-mestizo population. Thus, racial tension and uprisings were not problems there. There was virtually no African population. The Mapuche Indians were thoroughly defeated and conveniently tucked away in reservations in the south (a policy that still blemishes the nation's reputation today).

The existence of settlement frontiers is a second reason Chile's early governments survived. As the nineteenth century wore on, slow settlement of the frontiers to the north and south from middle Chile took place. This outward migration provided a safety valve for middle Chile's growing population. There were certainly frustrations among the migrants, particularly because of poor labor practices in the mines where many of them found work. Two small mid-century revolts took place in the frontier as a result. All the same, rather than creating a serious challenge to the authority of middle Chile, the frontier, gave an overflow population a sense of opportunity and hope.

A third reason why Chile's constitutional government survived is that it did not have a hollow frontier. A hollow frontier is one in which active settlement occurs only on the edge of an expanding frontier. No solid network of towns develops between the edge and the main area of settlement. Such geographical isolation could lead to injustices, misunderstandings, regional rivalries, violent clashes, and civil wars. In Chile, roads, railroads, and ocean shipping lines connected the country's frontier areas to middle Chile, the core area of settlement. Such lines of communication between people at the periphery and the center helped keep the nation together.

A successful nineteenth-century economy is a fourth reason why Chile's early governments survived for so long. Chile's output of copper and silver increased during this period. The country was the world's leading copper exporter by 1860, a position it still holds today. Agricultural production also increased. A mid-century boom in wheat sales to California and Australia proved temporary. Rising exports to the British market made up for that loss. Until the 1890s, Chilean wheat production was still greater than that of Argentina, Chile's main South American rival producer. The government invested tax money (mainly from nitrate exports) to build the continent's first telegraph network. The government and foreign investors built railroads into the interior and established steamship lines along the coast. This network was for interregional trade, but it also helped unify the nation politically. Just as important, the booming economy created jobs for Chileans, so they were less likely to complain about the shortcomings of their government.

THE EARLY DEMOCRATIC PERIOD (1925-1973)

Authors of the 1925 constitution modeled it after the U.S. Constitution. The charter divided the government into three equal branches: the executive, legislative, and judiciary. A house of deputies and a senate composed the legislative branch. After a few amendments, the constitutions gave all citizens of Chile the right to vote. The charter guaranteed other freedoms that true democracies have as well, such as the freedoms of assembly, religion, speech, and so on. The charter also gave the government the job of providing social security, including setting standards for public health, housing, and sanitation, and enforcing safety regulations in the workplace.

Conservative elements in Chile believed that government should not have such responsibilities. Shortly after the constitution took effect, there was a brief period of dictatorial rule under Colonel Carlos Ibanez. After that, the nation went through a sustained period of electoral democracy. A more serious rebellion rocked Chile in 1973, when Augusto Pinochet took over the government.

THE FALL OF DEMOCRACY UNDER PINOCHET (1973-1990)

In the late morning of September 11,1973, army tanks and air force planes bombarded the La Moneda, Chile's presidential palace. There had been rumors for months about a possible military coup. The Marxist policies of President Salvador Allende had lost the support of key members of his political coalition. There was a serious food shortage and rampant inflation, rising unemployment, and illegal seizures of private property by labor and trade unions. Allende and a handful of his closest advisors and personal bodyguards had rushed to La Moneda earlier that morning to discuss reports of a possible military uprising. Allende gave a radio address pledging his defense of his right to govern. A short time later, he was dead.

Facing the certain end of his presidency, he chose to take his own life.

General Augusto Pinochet, born in Santiago and educated in Chile's military academy, led the revolt. A military junta (a group of generals) ran the new government. Pinochet was its leader. During the 1970s, the junta suspended the constitution. It gave the military and national police force almost unlimited power. They arrested, detained, and jailed protesters without trials. Evidence indicates that Pinochet also directed a secret police force to track down former Allende supporters. This group tapped telephones, opened mail, and kidnapped suspects. Thousands of political prisoners were murdered, jailed, tortured, brutalized, or exiled. In an effort to completely silence critics, Pinochet and his military commanders closed congress, censored the media, purged the universities, burned books, outlawed political parties, and banned labor union activities. No one expected that the military regime would be so bloody and so long lasting, not even the coup's harshest critics.

By the early 1980s, Pinochet was confident that he was in control of the country. He eased up on his hold by allowing passage of a constitution in 1981. This constitution was rooted in the Constitution of 1925. Under Pinochet's watchful eye, authors of the Constitution of 1981 created a strong executive (president) but a weak congress and judiciary.

For example, it allowed Pinochet (who was the president) to dissolve the chamber of deputies if he saw fit. The charter also gave the president power to pick one-third of the senators. Pinochet's control was absolute. People were afraid to voice their opinions in public or private, for fear of the secret police. Nonetheless, with unemployment at record levels and cutbacks in welfare programs being felt everywhere, Chileans became increasingly militant in demanding an immediate return to democracy.

Despite these rumblings, Pinochet was still very confident in his control of the country. In 1989, he held a plebiscite (special vote) calling for the people to vote “yes” or “no” on whether they wanted him in office. A “yes” vote would mean that Pinochet would remain as president until 1998. A “no” vote would mean that new, open elections would be held in late 1989. The “no” voters won. A surprised Pinochet agreed to quit at the end of 1989.

TODAY'S GOVERNMENT

Ironically, Pinochet's 1981 constitution is the basis of Chile's modern democratic government. Revisions in 1989, 1993, and 1997 transformed the constitution into a democratic document. Some experts see further constitutional reform as necessary to complete the changeover to democracy.

In its present form, Chile's constitution pledges the three branches of government equal power through a system of checks and balances. It allows people of all political parties, ethnic backgrounds, and religious persuasions to take part in government. It also allows the people to elect the president. The people elect members of the legislature and municipal governments as well. The charter promises the right to vote to all citizens and foreigners who have resided in the country for more than five years, if they are 18 years of age or older. (Women got the right to vote in 1934 for municipal elections and in 1949 for national elections.)

The executive branch includes the president and his cabinet. The president must be at least 40 years of age and born in the country. He or she is elected to a six-year term and cannot serve two consecutive terms. The president appoints a cabinet of ministers to direct various functions of government. The makeup of the cabinet includes ministers of foreign relations, agriculture, finance, health, defense, public works, mining, housing, and so on. There are 18 cabinet ministries and 4 cabinet-level agencies. The president also appoints members of the judiciary and other officials to govern the nation's territorial divisions. Furthermore, the president appoints members of the Supreme Court, as well as all appellate court and local court justices. These appointments are final and not subject to approval by congress.

Chile's constitution gives the legislative branch the power to select a new president with a majority vote if two years or less are left in the presidential term. Should the vacancy occur with more than two years left in the term, the legislature must call for a nationwide presidential election.

The constitution provides for a bicameral (having two houses) legislature consisting of a senate and chamber of deputies (the equivalent of the House of Representatives in the U.S. Congress). Congress has a 48-seat senate. Senate members must be citizens, at least 40 years old, have completed high school, and have lived in the region they represent for at least four years. They serve eight-year terms, with half the senate coming up for election every four years. People elect 38 of the 48 senators. Nine senators receive appointments from the Supreme Court, the National Security Council, and the president. Four of these appointees must be former commanders of the armed forces. There is one senator for life. (The constitution entitles former presidents to a lifetime senate seat.) The chamber of deputies consists of 120 members, 2 for each of 60 congressional districts. All deputies serve four-year terms. When their term begins, they must be citizens, at least 21 years old, have graduated from high school, and have lived in the district they represent for at least two years.

The hierarchy of Chile's court system has four levels of jurisdiction. Beginning at the top, they are the Supreme Court, appellate courts, major claims courts, and local courts. The Supreme Court consists of 17 members. The Court reviews appeals by defendants who lost cases in the lower, appellate courts. Unlike the U.S. Supreme Court, the Chile Supreme Court does not review Congress' laws in order to determine if they go against the constitution. A special Constitutional Tribunal is set up for that purpose.

Chile has 16 appellate courts, each with jurisdiction over one or more provinces. The majority of these courts have 4 presiding judges, although the two largest courts have 13 members, and Santiago's Appellate Court has 25. The appellate courts rule on laws that apply to the provinces within their jurisdictions and hear appeals by defendants who lost their cases in the major claims and lower courts.

GOVERNMENTAL TERRITORIES

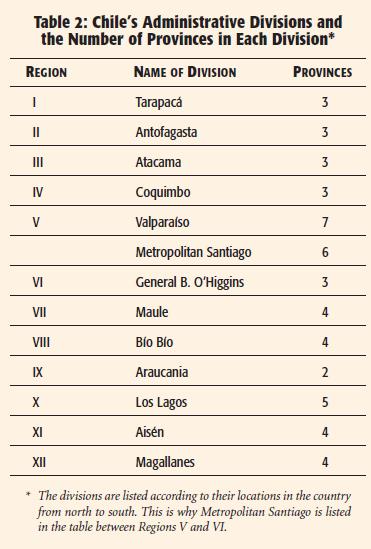

Chile is organized into a hierarchy of territories. From largest to smallest, the hierarchy includes administrative divisions, provinces, and communes. Like vertebrae of a spinal column, 13 large administrative divisions divide the narrow country (Table 2). Except for Metropolitan Santiago, the divisions include a bit of West Coast, Central Valley (or Inland Waterway), and Andean crest. (Metropolitan Santiago does not reach the coast.) Chile's president appoints an intendente (subtreasurer) to run each division. For organizational purposes, the government uses roman numerals to identify 12 of the 13 divisions. The numerals run one after the other from north to south, beginning with Region I at the north end of the country, and finishing with Region XII at the southern end. Metropolitan Santiago, which includes Santiago and its suburbs, is the thirteenth division.

Region XII (Magallanes) is the largest of the 13 divisions. It includes Chilean Antarctica, a wedge-shaped slice of the Antarctic continent. Metropolitan Santiago is the smallest of the 13 divisions, but it is by far the most populous area. Region XI (Aisen) has the smallest population. The region consists of remote islands of the southern archipelago and a highly glaciated section of the Andes.

Provinces make up administrative divisions. There are 52 provinces. Table 2 shows the number of provinces in each division. In order to even out the number of people living in each province, the central government has varied the area and number of provinces in each division. For example, Region I (Tarapaca) has a small total population, but a major city—Arica. The remainder of the region is largely empty desert. As a result, the province that includes the city of Arica is smaller than the other two provinces. In contrast, Region V (Valparaiso) is a densely settled province with many towns and cities, including the city of Valparaiso. This region is broken down into seven provinces that are about equal in area.

Communes make up the provinces. They include both urban and rural areas. Communes handle the nuts and bolts of running local government. They deal with traffic regulation, land use planning and zoning, garbage collection, sewage, water supply, beautification, and so on. Each commune with an urban area has a council and a mayor who serve four-year terms. Citizens elect the commune council, which in turn appoints the mayor.

The mayor picks delegates to run communes in remote rural areas. The mayor also proposes a budget and land use plans for the municipality. The council approves or rejects the mayor's proposals. It also approves local laws and rules and watches over the work of the mayor. The Chilean government provides an interesting Internet web page (in Spanish) with a map that shows the location of and data for all of the country's governmental territories.

NATIONAL BOUNDARY DISPUTES

Territorial boundaries are sometimes the subject of dispute between nations. The Chilean government has had three boundary disputes in recent years. Chileans and Argentines asked Pope John Paul II to settle a dispute over which country owned a cluster of three barren islands south of Tierra del Fuego. Although the islands themselves are insignificant, the country that owns them has fishing rights to a large area of the southern Atlantic Ocean. The popes representatives concluded that the three islands belonged to Chile, and the two countries signed a treaty agreeing to the Popes decision in 1985.

A second dispute involves Chile's northern border and is ongoing. Bolivia and Peru want to reclaim territory they lost to Chile in the War of the Pacific (1879-1884). Bolivia wants to reestablish the access it had to the Pacific Ocean before the war.

Entry to the Pacific would require a corridor of land through northern Chile, but it would improve Bolivia's international trade. Chile would lose rights to minerals and water in the corridor. The dispute led to the cutoff of diplomatic ties between Chile and Bolivia in 1978. The two countries no longer operate embassies in the other's capital. They do maintain consulate offices, however, so that they can issue visas and passports to citizens of the other country. In 1979, on the one-hundredth anniversary of the start of the war, Peru's military signaled that it might try to retake the land it had lost in the war. Chileans primed for war, but the threat never materialized. Chile and Peru still have formal, although strained, diplomatic ties.

A third boundary dispute involves Chile's claim to a wedge-shaped section of Antarctica. The meeting of 53° and 90° west longitudes at the South Pole defines the wedge. In 2002, 130 Chileans, mostly scientists and their staffs, lived in Chilean Antarctica. Great Britain and Argentina claim areas that overlap Chile's claim. This dispute is not a pressing concern, because territorial claims to this continent are on hold by international agreement.

FOREIGN RELATIONS

Chile is a founding member of the United Nations. The country has been taking on key roles in the UN since its return to democracy in 1990. It served a two-year term on the United Nations Security Council in 1996-1997 and began a second two-year term in January 2003. It is also a member of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. In recent years, Chileans have served as UN peacekeepers in Cyprus, Palestine, Pakistan, and India.

The country is also active in Latin American and other regional summits. Such meetings bring together diplomats from many countries. The envoys discuss problems and concerns that their countries have in common. Chile hosted the second Summit of the Americas in 1998. It presided over the Rio Group (an organization of 19 Latin American and Caribbean countries) in 2001. The country is also a member of the Organization of American States (OAS). Chile was a key supporter of the common defense provisions of the OAS following the September 11,2001 terrorist attacks on the United States. The country held the fifth conference of the Ministers of Defense of the Americas in 2002. It is also a member of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum.

Chile is also seeking trade with other countries. It joined the APEC forum in an effort to boost commercial ties to Asian markets. It has also entered into Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), which stimulate trade by reducing or eliminating tariffs (taxes on imports and exports) between trading partners. Chile has FTAs with Canada, Costa Rica, Ecuador, the European Union, Mexico, South Korea, and Venezuela. It also has a FTA with the European Free Trade Association (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland). Chile signed an FTA with the United States, its main trading partner, in June 2003. Chile is also an associate member of Mercosur, which includes Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, as are Bolivia and Peru. Membership in Mercosur allows Chile special trading access to neighbors.

RECENT NATIONAL POLITICS (1990-PRESENT)

After Pinochet stepped down, Chile's congress amended the 1981 constitution to return the nation to democracy. The country has had freely elected presidents since then. A constitutional amendment in 1993 made presidential terms six-year terms and nonconsecutive.

The major parties include the Christian Democrat Party, the National Renewal Party, the Party for Democracy, the Socialist Party, the Independent Democratic Union, and the Radical Social Democratic Party. The Communist Party (champion of the Marxist-Leninist philosophy) has not won a congressional seat in the last four elections. Chileans' politics involve a lot of coalition building, because there are so many political parties. In the 2001 congressional elections, the conservative Independent Democratic Union surpassed the Christian Democrats for the first time to become the largest party in the lower house.

Political ideologies divided government in the past but are less of a problem today. For example, politicians no longer give serious thought to the radical change that a one-party communist system would require. Chileans agree that democracy is working. As a result, they have turned their energies away from ideology and toward concrete issues such as growing their nation's economy.