What Are Some Other Types of Wind Storms?

SEVERE WEATHER INCLUDES VARIOUS WIND STORMS in addition to tornadoes and cyclones. Some of these other storms — with interesting names like waterspouts, microbursts, haboobs, and derechos — can be extremely dangerous. What are their characteristics, how do they form, and where do they occur?

Waterspouts

A waterspout is a rotating, columnar vortex of air and small water droplets that is over a body of water, usually the ocean or a large lake. There are two kinds: tornadic waterspouts and fair-weather waterspouts. Waterspouts are usually less intense than tornadoes, with smaller funnel diameters, weaker wind speeds, shorter lives, and shorter path lengths.

Some waterspouts resemble tornadoes, and some are actual tornadoes that either formed over the water or formed over land and later moved over the water. These large, storm-related waterspouts form in the same way tornadoes on land form — strong updrafts associated with a powerful thunderstorm, such as a supercell thunderstorm. Such waterspouts, like any tornado, are dangerous, but are generally not as powerful because the cooler surface temperatures over water limit the atmospheric instability and the amount of lifting. This type of tornadic waterspout can be recognized by its association with a thunderstorm and is much larger and stronger than a fair-weather waterspout.

The other type of waterspout is associated with normal cumulus clouds, and not typically with thunderstorms. Since these form when it is not raining, hey are called fair-weather waterspouts. A fairweather waterspout is a rotating column of air that starts from wind shear near the water that gets lifted upward by mild updrafts that are also forming the overlying cumulus cloud. The water in the spout was not picked up from the underlying water, but is condensation produced as the air is rising and cooling. This type of waterspout is most common in the tropics, such as in the Florida Keys, but it can also form in mid-latitudes, like on the Great Lakes.

Derechos

A derecho, whose name is derived from the Spanish word for “straight,” is a regional windstorm characterized by strong, nonrotating winds. The winds can advance across huge areas and cross several states in a matter of hours. Wind velocities can be hurricane-strength and can cause damage to trees, power lines, and other structures.

This map shows a series of radar images (strongest echoes in red) capturing the progression of a single derecho that started near the Great Lakes (in the upper left) and moved east with time. As the derecho moved, it spread, forming a radar echo in the shape of a bow (like an archer's bow). Such a bow echo is characteristic of a derecho. Note how rapidly this derecho traveled, moving from Lake Michigan to the Atlantic Ocean in about 10 hours, at an average speed of about 150 km/hr.

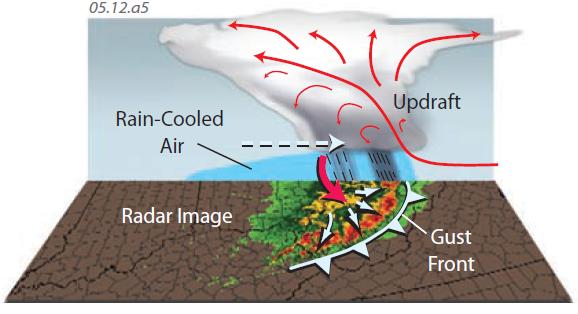

Derechos are caused by downdrafts (red arrow in this figure) from a band of thunderstorms in a multi-cell storm, where a downdraft from one thunderstorm forms or strengthens an adjacent thunderstorm. Such downdrafts can be sustained for a long time and over long distances, forming a derecho. Embedded within a derecho may be other types of wind storms, including tornadoes, squall lines, and microbursts.

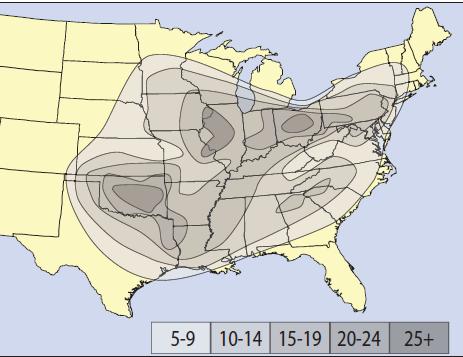

On this map, contours depict the number of derechos experienced in different areas. The Ohio Valley, Upper Midwest, and Great Plains of the U.S. may experience more derechos than any place in the world. Summer is the most common season for derechos. They are long lived and can occur at any time of day or night.

Derechos can be accompanied by a very distinctive and ominous type of cloud called a shelf cloud, a spectacular example of which is shown in this photograph. Similarappearing clouds can form in other ways, such as near tornadoes and dry lines.

Microbursts and Other Powerful Downdrafts

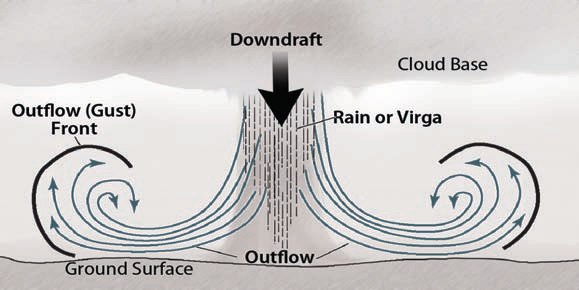

Microbursts are brief but strong, downward-moving winds (downbursts) that can flatten trees or structures. Unlike tornadoes, microbursts produce winds that move in a straight line, rather than rotating, so sometimes people refer to microbursts as straight-line winds. A microburst can be classified as being wet or dry, depending on whether it is embedded within a thunderstorm. They can be more severe than some tornadoes, and although only lasting a few seconds, are a major aviation hazard, primarily because of the wind shear associated with them.

This photograph shows a wet microburst within a thunderstorm. It is expressed as a downward burst of moist air that, in this case, is carrying an increased amount of rain. Note how the rain is being spread out in all directions as it nears the ground. Microbursts generally affect a relatively small area, but they can extend over areas as large as several counties. In either case, their duration is short (measured in seconds or minutes).

Dry microbursts are downdrafts, generally not associated with rain. Under these conditions, they may pick up dust and loose materials, moving them as a small dust storm, or haboob described below. Both wet and dry microbursts can be strong enough to cause significant damage, with or without dust.

Under some circumstances, a downdraft will carry down a diffuse column of raindrops that evaporate before they reach the ground. This phenomenon, called virga, can occur for a variety of reasons. Where associated with downdrafts, the descending air can compress and heat up as it is pushed downward, helping evaporate the water drops before they reach the ground.

The figure above illustrates the setting in which most microbursts occur. Late in the life cycle of a thunderstorm, the lifting power of the convecting air begins to be overwhelmed by the downward force of precipitation and downdrafts. These cool the lower parts of the cloud, the air below, and the surface, limiting the heat available for additional convection. At this point, the thunderstorm can start to collapse (the stage shown in the figure above). This can cause a very strong downdraft, which upon reaching the surface causes a microburst. Microbursts can move out from a dying thunderstorm in several directions or mostly in one direction. The tell-tale sign of a microburst is a “starburst” damage pattern, where features are blown radially, rather than a pattern of damage that indicates rotation around a central core (as in a tornado).

Haboobs and Dust Devils

1. A name applied to severe downdraft-related, nonrotating dust storms is haboob, derived from an Arabic word for “blasting.” These are formed in a similar way to microbursts, at the collapse of a dying thunderstorm. They can pick up dust from desert areas and plowed fields, producing a thick cloud of dust that rapidly advances across the landscape. They can damage windows, cause respiratory issues, and create very hazardous driving conditions as visibility drops to a few meters in a matter of seconds.

2. Often overlooked as a hazardous weather phenomenon is a dust devil (also called a whirlwind or simply a dust storm). Like other rotating storms, these develop when the atmosphere is extremely unstable and upper-level patterns encourage rising motion. The upward motion at the surface creates strong pressure gradients, which strengthen the system seemingly uncontrollably. Eventually, the energy is expended, friction slows the wind, and the dust devil dissipates.

3. Dust devils and haboobs form in arid regions, so their strength is limited by the generally small latent energy released in condensation and deposition. But the thick dust, in addition to reducing visibility, can remove topsoil and erode the landscape.