Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia

POPULATION: 96.51 million (2014)

AREA: 435,184 sq. mi. (1,127,127 sq. km)

LANGUAGES: Amharic (official); Gallinya, Tigrinya, Orominga, Somali, Italian, English

NATIONAL CURRENCY: Birr

PRINCIPAL RELIGIONS: Christian 40% (Ethiopian Orthodox), Muslim 45%, Traditional 15%

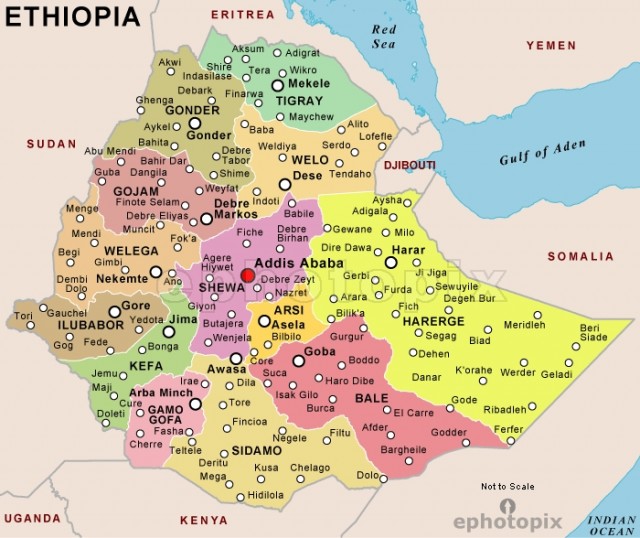

CITIES: Addis Ababa (capital), 2,431,000 (1999 est.); Dessie, Dire Dawa, Harar, Gondar, Jimma, Mekele, Nazret

ANNUAL RAINFALL: Varies from 104 in. (2,640 mm) in southwest to 4 in. (100 mm) in the Danakil Depression.

ECONOMY: GDP $54.80 billion (2014)

PRINCIPAL PRODUCTS AND EXPORTS:

- Agricultural: coffee, sugarcane, cereals, potatoes, vegetables, livestock, animal hides and skins

- Manufacturing: textiles, food processing, beverages, cement

- Mining: gold, natural gas, platinum, copper, potash, iron

GOVERNMENT: Oldest independent country in Africa. President elected by House of People's Representatives. Governing bodies: House of Representatives and House of Federation (legislature); Council of Ministers, appointed by prime minister

RULERS SINCE 1930:

- 1930–1974 Emperor Haile Sellassie I (excluding Italian occupation of 1936–1941)

- 1974–1977 Provisional Military Administrative Council (led by General Aman Andom (1974), Brigadier General Tafari Benti (1974–1977)

- 1977–1991 Lieutenant Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam

- 1991–1995 Acting President Meles Zenawi

- 1995– President Negasso Gidada

ARMED FORCES: 120,000 (1998 est.)

EDUCATION: Compulsory for ages 7–13; literacy rate 35%

With a culture dating back to early times, Ethiopia rivals Egypt as one of Africa's great ancient civilizations. Beginning around 100 B.C., a series of kingdoms and empires arose in Ethiopia. The country managed to remain independent in the 1800s and early 1900s when European powers took over much of Africa. In recent times, Ethiopia has been battered by decades of revolution, rebellion, and deadly famine. Today the country struggles to modernize its economy and to become more democratic.

GEOGRAPHY AND ECONOMY

Located in the interior of the Horn of Africa, Ethiopia is bordered on the west by SUDAN, on the south by KENYA, on the east by SOMALIA, on the northeast by DJIBOUTI, and on the north by ERITREA. The country's economy has long been based on local grains and animal herds, as well as the export of coffee.

Land and Climate

The terrain of Ethiopia consists basically of cool, wet highlands surrounded by hot, dry lowlands. The broad Ethiopian Plateau in the Western Highlands reaches altitudes between 8,000 and 12,000 feet. Dividing the Western Highlands from the Eastern Highlands is the Great Rift Valley, a low region dotted with lakes and volcanoes.

However, some of its ancient peaks rise above 13,000 feet. The Rift Valley runs roughly north and south across all of central Ethiopia, with the arid Danakil Depression at its northern end.

The Western Lowlands, bordering on Sudan, include Ethiopia's largest river basin with the Baro, Blue Nile, Atbara, and Tekkeze rivers. Rising in the Western Highlands, the rivers pass through the Western Lowlands on their way to the White Nile in Sudan. The Eastern Lowlands in the southeastern regions of Ethiopia include the Sidamo-Borana plain as well as the arid regions known as Hawd and Ogaden.

Land Use

Although the northern regions of the Highlands have irregular rainfall, the southwest enjoys regular periods of precipitation. Peasants in the north have grown grains for thousands of years, but these crops were introduced in the south only in the 1800s. In the humid southwest, peasants grow ensete, also known as the false banana tree. They scrape the stems of this tree to produce a dough that they leave in the ground to ferment.

Since the 1800s northern peasants have begun to raise cash crops. The main one, coffee, accounts for more than half of Ethiopia's export earnings. The area around the city of Harar grows and exports khat, a mild drug popular among Muslims for chewing. In the Lowland regions, nomadic cattle herders supply a variety of animal hides including oxen, sheep, and goats.

Land use changed dramatically in 1979, when a military government led by MENGISTU HAILE MARIAM launched the Green Revolution. This was an attempt at land reform patterned after the system of large stateowned farms used in the Soviet Union. The state farms featured a single crop, mechanical equipment, and many workers. The government forced many peasants to relocate. In the mid-1980s, nearly 600,000 households were moved to hastily developed, unhealthy sites in the southern Lowlands. By 1988 the government had forced another 12 million people from various places in Ethiopia to settle together in large villages.

HISTORY

The history of Ethiopia is inseparable from the history of the Horn of Africa, a triangular landmass on the eastern corner of the continent. The Horn has been a cradle of humanity, a crossroads of civilizations, and a symbol of freedom. Studies by archaeologists reveal that the region was home to the most distant human ancestors and later became an area where people developed stable farming communities.

Kingdom of Aksum

According to ancient records, the Egyptians knew Ethiopia as the land of Punt, supposedly a vast area that included what is now the Somali coast and part of the Ogaden Plateau. Punt was known as a source of incense and myrrh. Later, around 100 B.C., the kingdom of AKSUM arose. The center of a caravan trade based mainly on ivory and slaves, Aksum grew into a regional power. In time the kingdom stretched from the Ogaden in the east to the gold-producing region bordering the Blue Nile River in the west and even minted its own coins.

Aksum adopted Christianity in the 300s. In the 500s the kingdom defended its faith by sending armies across the Red Sea to protect Christian communities persecuted by local Jewish inhabitants. Aksum's massive military campaign took a toll on its rulers. They were further weakened when Muslims took control of the trade along the Red Sea in the 700s. The empire finally collapsed in the 900s, after rebels destroyed Aksum. The rebel leader, according to tradition, was a Jewish woman. The new rulers, the Zagwe dynasty, brought a new culture and language, but they were faithful to Christianity.

Christian and Muslim States

In the late 1200s Yekuno Amlak seized the throne. Claiming to be a descendant of Aksum's former rulers, he established the Solomonic dynasty. He and his descendants were able to control important southern trade routes from a base in Shewa, a small southern kingdom established by Muslim traders.

For more than two centuries, a fierce rivalry existed between the Solomonic rulers in the north and several Muslim states in the south. Frequent raids and wars resulted in a weak northern Christian state, but the Muslim states were also fairly unstable. The northern rulers led an unsettled life, traveling in royal camps. They had no permanent capital. Their massive armies and many attendants caused more harm to the land and crops than locusts. A royal visit completely upset the area's environment and took a heavy toll in human lives.

Conditions were no better in the Muslim south. Wars among the states and conflicts with the north left these kingdoms very weak. People moved around in great numbers. Economic development was limited, and cultural centers developed in only a few cities. In addition, wars in the Middle East between European Crusaders and Muslims resulted in a decline in international trade.

The Wars of Gran

At the start of the 1500s, the Red Sea commerce revived and the Turks and the Portuguese became active traders in Ethiopia. The first official representative of the Portuguese arrived in 1520. At the same time, the southern Muslim peoples were being organized by a leader named Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi. His nickname, Gran, means “the Left-Handed.”

Gran won a major battle against the Christian north in 1528, and he attempted to bring the entire Horn of Africa under his control. The Turks sided with Gran, but he later expelled them from his territory. Meanwhile, the Portuguese supported GALAWDEWOS, the defeated Christian ruler, and made an effort to punish Gran. The years of warfare finally ended in 1543, when a Portuguese bullet fatally wounded Gran. The wars sapped the energy of both the north and the south. The way was clear for another major force, the Oromo, to enter the central Highlands. During the 1500s the Oromo overran the Horn of Africa. They absorbed peoples and old states all over Ethiopia, challenging the Solomonic emperors who now ruled a shrinking empire from their court at Gondar.

HISTORY SINCE 1600

During the 1600s the Solomonic emperors relied on an alliance of their Christian nobles and some Oromo nobles to protect the realm from the rest of the Oromo peoples. However, the two groups of nobles fought constantly for power and position. By the beginning of the 1700s, their rivalry had broken up the empire and ushered in the “Age of Princes,” 150 years of anarchy.

Two Emperors

The economy of the north collapsed during the Age of Princes. Warring armies ruined the countryside. Only the central highland region of Ethiopia remained untouched and continued to prosper, especially in the Shewa district where trade thrived. The Age of Princes ended in the mid-1800s when a soldier named Kassa Hailu built up a small but effective army and challenged the authorities in Gondar. In 1855 he was crowned emperor as Tewodros II. Tewodros tried to centralize power in Ethiopia, but his policies were opposed by nobles and the church. A minor dispute with British diplomatic representatives led the British to send in an army. Lacking popular and military support, Tewodros was defeated and committed suicide to avoid capture by the British.

Yohannes IV of Tigre succeeded Tewodros in 1872. The new emperor called on local lords to become part of a federation under his rule. King Menilek of Shewa at first refused, but he joined when Yohannes brought military force against him. Another challenge came in 1885, when Italians landed troops in Eritrea. Yohannes succeeded in confining them to the coastal regions. In 1889 he was shot and killed in Sudan, where he had gone to put down attacks along the border.

The Reign of Menilek

Soon after the death of Yohannes, Menilek declared himself emperor. He quickly signed a treaty of trade and friendship with the Italians, but he later learned that the Italians believed that the treaty made Ethiopia a colony of Italy. Menilek delayed any action against the Italians while he worked to restore his economy, to trade for modern weapons, and to deal with the famine and disease that were sweeping East Africa. These measures, along with two years of good grain harvests, enabled Menilek to gather his forces against the Italians.

The Italians ridiculed Menilek and the very idea of an Ethiopian nation. They believed that their 35,000 troops, equipped with out-ofdate weapons, could defeat Menilek's 100,000 well-armed Ethiopian soldiers. On the morning of March 1, 1896, the Italians appeared on the heights above the Ethiopian camp. Menilek attacked before the Italians could dig in, and by noon the Italians were in retreat. The Treaty of ADDIS ABABA canceled the previous treaty with Italy, but it gave the Italians control of Eritrea.

Over the next ten years, Menilek expanded Ethiopia to its present borders. Surrounded by European colonial powers, Menilek modernized his capital at Addis Ababa, opened schools and hospitals, and oversaw the construction of better communications in Ethiopia and a railroad from Addis Ababa to Djibouti. In 1909 Menilek suffered a stroke and was succeeded first by his grandson and then his daughter.

Haile Selassie I

Menilek's children were dominated by a powerful noble, Ras Tafari Makonnen, who also worked tirelessly to modernize Ethiopia and keep it independent. When Menilek's daughter died in 1930, Tafari declared himself emperor. He was crowned Emperor HAILE SELASSIE I, meaning “Strength of the Trinity.”

The emperor issued a national constitution and continued development programs for roads, schools, hospitals, communications, and public services. As a result, the economy improved, and taxes from coffee exports brought new wealth to the government. However, Haile Selassie's successes prompted the Italians to invade Ethiopia in 1935. The emperor was forced to flee while the people resisted the Italians in the countryside. During World War II, the British supported Haile Selassie and prepared an Anglo-Ethiopian invasion. The Italians withdrew from Ethiopia in 1941.

The 1950s brought a new period of unrest in Ethiopia. In 1952 the United Nations approved the country's request for a federation with Eritrea. Then in 1963 Haile Selassie's government ended the federation and declared Eritrea a province of Ethiopia. Many Ethiopians opposed this move, and the Eritreans rebelled. By the early 1970s, Ethiopian troops were fighting a war in Eritrea while putting down tax rebellions in other regions of the country. At the same time, high oil prices dented the economy, and drought and famine overtook the north. The aging emperor could no longer cope.

The Revolution

The last of the Solomonic emperors, Haile Selassie, was removed from power in 1974 by a group of military officers known as the derg, meaning “committee.” The first head of the revolutionary state, General Aman Andom, was overthrown within months and was followed by General Tafari Benti. General Tafari nationalized Ethiopian land and pronounced Ethiopia a socialist state before he was killed by rivals.

His successor, derg chairman Lieutenant Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam, turned Ethiopia into a communist state with all power in the central government. He accepted military help from the Soviet Union to fight wars against rebels in Eritrea and an invading Somali army in the Ogaden region. At the same time, his government created associations of peasants to farm the countryside. This organization led to smaller harvests and damaged farmlands, resulting in a disastrous famine in 1984. Donations of grain from Western nations the following year gradually relieved the famine.

Toward the end of the 1980s, Mengistu's army suffered some serious setbacks. The Eritrean rebels and their allies succeeded in pushing back the Ethiopian forces. The Soviet Union refused to send more arms and advised Mengistu to make peace. One of the most powerful of his opponents was the Ethiopian Peoples' Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). By May 1991 the EPRDF controlled most of the provinces around Addis Ababa and insisted that Mengistu resign. Mengistu fled to Zimbabwe and the EPRDF marched into Addis Ababa and assumed power under Meles Zenawi.

The Eritreans were left in control of their own territory, and two years later they formally declared independence. However, the peace between Eritrea and Ethiopia was uneasy, and in 1998 fighting erupted again over a disputed border in the Tigre region. Many called it a “useless” war, but it continued for two years and killed tens of thousands of people. At last representatives of both sides met in ALGERIA. They signed a peace treaty in December 2000.

Inside Ethiopia the ruling EPRDF had strong popular support throughout the 1990s. Nevertheless it had to contend with a number of small uprisings and other challenges to its power. At the same time, drought threatened in the countryside, where the state still claimed control over farms.

PEOPLES AND CULTURES

Ethiopia has a rich and diverse ethnic background. Ethiopians speak languages of four different language families, though they share a common written script called Ge'ez. Among the country's major ethnic groups are the AMHARA, Tigre, and Oromo. Their ancient cultures may be seen in their art and architecture, which draws heavily from both Christianity and traditional African culture.

The Amhara and Tigre

Until the end of World War II, Ethiopia was known to the Western world as Abyssinia and its people as Abyssinians. This term refers mainly to the Christian peoples who are properly called the Amhara and the Tigre. These people speak Amharic and Tigrinya, languages of the Semitic family that also includes Arabic and Hebrew. The homelands of the Amhara and Tigre are spread over the western and northern Highlands of the Ethiopian Plateau. The Amhara, the major ethnic group in Addis Ababa, have moved in recent centuries into the Western Lowlands near the Blue Nile River. The Tigre live mainly to the north of the Amhara, inhabiting the province of Tigre along the border with Eritrea.

Most of the Amhara and Tigre are devout followers of the ETHIOPIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH. They are mainly settled farmers who also raise livestock on their lands.

The Oromo

The Oromo are spread over nearly half of Ethiopia. They live along the Ethiopian Plateau, from the largely Muslim province of Harar on the east, to the Kenya border on the south, and westward to the Blue Nile. Numerically the largest group of Ethiopians, the Oromo are divided into a dozen smaller groups. All the Oromo speak a common language, which belongs to the Cushitic family.

After the 1500s some Oromo settled lands next to the Amhara and Tigre and adopted many of their living patterns and agricultural practices. However, the Boran and Arussi divisions of the Oromo follow a

culture of cattle herding shared by other East African peoples. The Boran and Arussi regard cattle as status symbols and use them in ritual sacrifices.

Islam, which had its center in the city of Harar, spread northward with the eastern Oromo during and after the 1500s. New Muslim populations included not only the Oromo but also the Raya, Somali, and Afar. Today these people are independent herders who mine salt in the hot lowlands of the Danakil Depression. Throughout the Oromo settlements, traditional religions exist alongside Muslim and Christian worship. The Falasha peoples (also known as Beta Israel) follow the Jewish religion. In recent years many of them have migrated to Israel.

Other Ethiopian Ethnic Groups

The lake peoples of the Great Rift Valley include the Sidamo and Konso ethnic groups. Most are settled farmers, although the Arbore are herders.

The Kafa and Janjero live along the southern stretch of the Omo River. Their languages are part of the Omotic language family. Until about 1900, the Kafa and Janjero had independent cultures centered around elaborate rituals. They grow ensete and several other grains and also trade extensively in gold and ivory. Their small kingdoms had complicated structures that were unusual for their size and region.

The Sudanic peoples, whose languages belong to families found in the eastern SAHARA DESERT and along the NILE, live in scattered settlements along the length of Ethiopia's border with Sudan. Most live in permanent settlements where they cultivate grains and root crops. Those living along the banks of the Baro River supplement their diet with fish.

Cross-Cultural Ties

Christians, Muslims, and followers of indigenous religions often live as neighbors in the same villages. They participate in the same community events and share any food or drink that does not violate their religious laws. The last outbreak of religious conflict in Ethiopia was in the 1500s, when the Gran launched his war against the Christian north. In the past, trade in goods and services linked the diverse peoples of Ethiopia, even those that may have been enemies. It remains to be seen whether these ties remain strong under modern governments.

Art and Architecture

For thousands of years, Ethiopia has been a major crossroads for the peoples of Africa, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean. The country's art and architecture, as diverse as its people, reflect the richness of its past. The art that has been most famous and most thoroughly studied is associated with the Tigre and Amhara of the highlands. Remains of palaces and temples, as well as stone sculpture and metal objects, date back 2,000 years or more.

The present town of Aksum still contains traces of the great Aksumite empire. The remains include large stone palaces built on raised platforms, royal tombs lined with carved stone, and tall stone monuments that mark the tombs of Aksum's ruling elite. Aksum's Christian traditions appear in its early churches.

Ethiopia's most famous churches, however, were built during and after the 1100s. These contain the oldest Ethiopian religious paintings still in existence. Over the centuries, Ethiopian priests and monks painted on the walls of churches, on wood panels, and in religious texts to inspire believers. They obviously interpreted their faith through Ethiopian eyes. Christian subjects are often depicted in Ethiopian settings and society.

The art of the Muslim peoples in eastern Ethiopia resembles that of their neighbors in Somalia and the Arabian peninsula. Among the main art forms are silver jewelry and multicolored baskets. The baskets serve a practical use as containers for milk, butter, and water. But in their woven designs and the way they are hung on walls, the baskets record the history, as well as the social and economic position, of their owners.

The Gamu people of the southern highlands are known for fine weaving. The women grow cotton and spin the thread, and the men weave the cloth. Perhaps the most distinctive artistic tradition in this area is the building of magnificent “basketry houses.” These structures are shaped like cones, often reaching 20 to 30 feet high. Made of bamboo strips, they are covered with either barley or wheat straw or bamboo stems.

Since the mid-1900s a number of Ethiopian artists have gained international fame for their work. Among them are Gebre Kristos Desta, Afewerk Tekle, Skunder Boghossian, and Zerihun Yetmgeta. Often the artists combine Ethiopian with European and international traditions. (See also Archaeology and Prehistory; Art; Christianity in Africa; Crafts; Ethnic Groups and Identity; Humans, Early; Languages.)