What Is a Tropical Cyclone?

HURRICANES AND OTHER TROPICAL CYCLONES are some of nature's most impressive spectacles. These immense seasonal storms form over warm, tropical waters and can cause extremely heavy precipitation, all the while deriving energy from latent heat released by condensation and deposition. In the Atlantic and eastern Pacific, the most intense type of tropical cyclone is called a hurricane while in the western Pacific and Indian Oceans, the terms used are typhoon and cyclone, respectively. Tropical cyclones take days to traverse an ocean and spread energy as they move across the globe. How do such storms form, and how are they sustained?

What Are the Characteristics of a Tropical Cyclone?

Tropical cyclones, hurricanes, and typhoons are characterized by low atmospheric pressure, large areas of strongly rotating winds, locally elevated sea levels, high wind-driven waves, coastal flooding and erosion, and river floods as the storm passes inland.

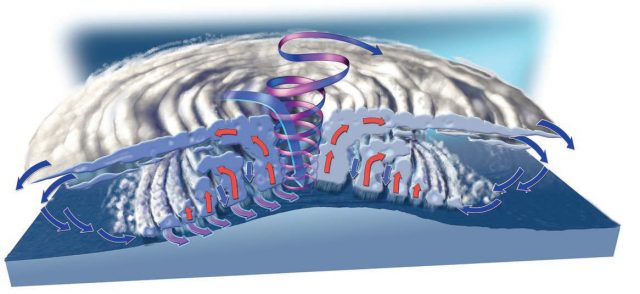

1. Tropical cyclones are huge, circulating masses of clouds and warm, moist air. They are zones of low atmospheric pressure that cause air to rise and condense, creating locally intense rainfall.

2. Warm tropical ocean waters fuel tropical cyclone formation. Water vapor evaporated from the sea surface mixes with the air, rises, cools, and produces clouds, releasing energy during condensation, which warms the air around it. This energy further enhances the upward motion, drawing more surface moisture to replace the rising air. In this way, tropical cyclones, once formed, provide their own fuel (energy).

3. If the tropical cyclone encounters additional warm water in its passage, extra energy is input to the storm, winds increase, and the storm grows in strength and size. A tropical cyclone dissipates when it passes over land, cold water, or mixes with much drier air.

4. Differences in atmospheric pressure between the surrounding environment, the tropical cyclone, and the center cause sea level to “buckle” by several inches. This effect is greatly exaggerated in the figure above to make it more visible. This mound of water can add to flooding problems when the cyclone reaches land, an event called landfall.

5. Like all enclosed low-pressure zones (cyclones), the Coriolis effect causes tropical cyclones to spiral counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. The storm's overall track is steered by air pressures and currents high in the atmosphere. The track is greatly influenced by ridges and other areas of high pressure, which can block or deflect a cyclone, either toward or away from land.

6. Dry air flows down the center of the storm, compresses, and evaporates clouds, forming a cylinder of relatively clear, calm air, called the eye. Sinking formed this eye, a hole down into the clouds, in Hurricane Ike in 2008.

7. The strongest winds and most severe thunderstorms are usually found within the eyewall — the area immediately surrounding the eye.

8. In the Northern Hemisphere, the right front quadrant is the most destructive part of the storm. This is the zone where the counterclockwise winds push the waves, called a storm surge, onshore with additional momentum.

Why Do Tropical Cyclones Rotate?

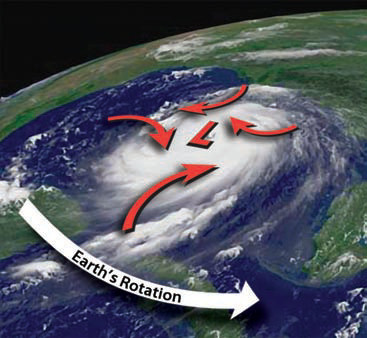

Tropical cyclones, like mid-latitude cyclones, are a result of multiple forces that influence where and how a cyclone moves. The pressure gradient force acts to move air into the lower pressure from all sides, but this flow of air is deflected by Earth's eastward rotation — the Coriolis effect. The Coriolis effect is fairly weak at low latitudes, but increases with the linear velocity of an object, like fast-moving winds associated with a tropical cyclone. This figure is a labeled satellite image of Hurricane Irene in 2011, a very large hurricane that caused extensive damage in the Caribbean, Gulf Coast, and the East Coast of the U.S.

The Coriolis effect deflects moving air to the right of its trajectory in the Northern Hemisphere (as shown by the red arrows on this figure) and to the left of its trajectory in the Southern Hemisphere. This produces a vortex shape and rotation of the entire cyclone system, with the now-familiar counterclockwise spin in the Northern Hemisphere and a clockwise spin in the Southern Hemisphere.

Where and How Are Tropical Cyclones Formed?

Tropical cyclones begin in the tropics as relatively weak disturbances in normal patterns of air pressures and wind directions. Few disturbances develop further, but some are dramatically strengthened by the environments through which they pass, attaining low-enough pressures and high-enough wind speeds to become a tropical cyclone. Here, we examine a common scenario that generates tropical cyclones over the Atlantic Ocean.

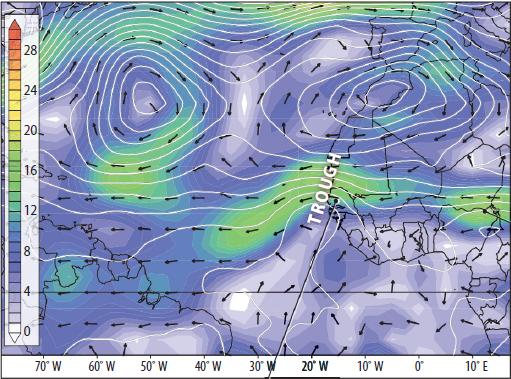

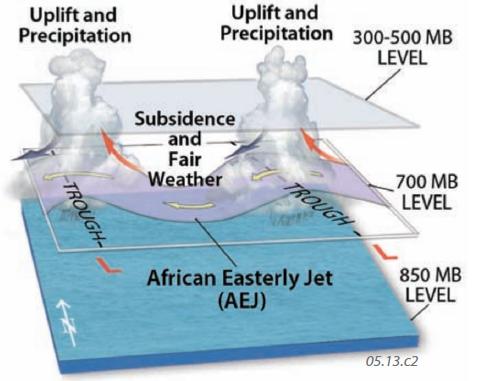

1. Tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Ocean often begin over or near Northwest Africa in association with a west-flowing stream of air in the northeast trade winds called the African Easterly Jet (AEJ), shown on the map to the left. The lines on the map are isohypses at the 700 mb level, and colors indicate wind speeds at a slightly higher level (red, yellow, and green are fastest). The relatively fast winds (green belt) of the AEJ flow across the arid regions of Africa. Note that the jet has wavelike bends north and south, similar to those observed for the polar front jet (Rossby waves).

2. The waves in the AEJ are termed easterly waves because the bends propagate from east to west. Since lower pressure is on the equatorward side of the AEJ closer to the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), the poleward limit of the wave describes an area of low pressure, called a trough. Like those in the mid-latitudes, troughs are associated with low pressure, lifting air, and cloudy or stormy weather. If a westward-traveling easterly wave encounters conditions favorable for further strengthening, such as warm sea temperatures, it can incrementally grow into a tropical depression, tropical storm, and hurricane.

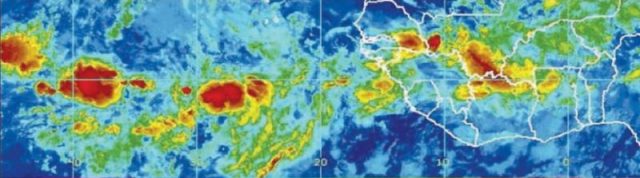

3. This color-enhanced satellite image shows a belt of thunderstorms (in red) associated with westward-moving easterly waves and tropical depressions. The easternmost wave (on the right side of the image) is still over Africa, where it formed, but ones to the left have been carried westward over the Atlantic Ocean by the west-blowing trade winds (which dominate surface winds in this region). As the thunderstorms move over the warm waters of the Atlantic, they can strengthen.

4. This figure shows that the east side of a northward bend in the AEJ (a trough) is associated with lifting and unsettled weather; the west side experiences fair weather. The explanation for this is similar to that for Rossby waves. If the storm can survive its trip through the west side of the wave, it may intensify afterwards.

Site of Origin and Tracks

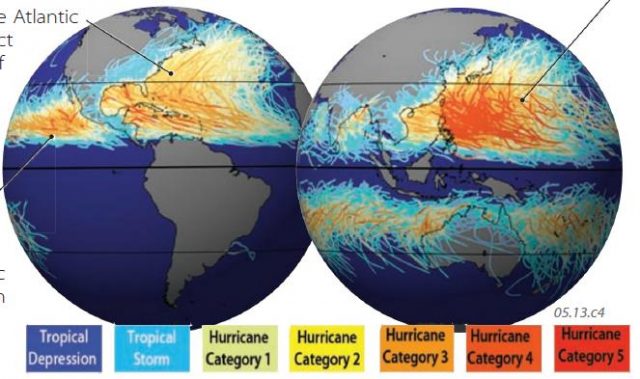

5. A tropical cyclone forms under specific conditions limited to certain regions and then travels along a path called a storm track. These globes display global storm tracks of tropical cyclones in various parts of the world, colored according to strength. Tropical storms originate over warm water and mostly travel between 10° and 15° latitude and the subtropics — they cannot cross the equator. Note a general lack of tropical cyclones right along the equator, due to the absence of the Coriolis effect there. The locus of activity shifts seasonally, following the migration of the overhead Sun and the regions of the warmest water.

6. Tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Ocean, the ones that affect the Gulf and East Coast of the U.S., mostly start west of Africa (related to the AEJ) from June 1 to November 30, the Atlantic Hurricane season.

7. Tropical cyclones, including hurricanes, also form in the tropical Pacific Ocean, but typically begin earlier, from May 15 through November 30.

8. Tropical cyclones in the western Pacific and the northern Indian Ocean mostly form from June to November, but can occur at any time of year. Most in the Southern Hemisphere form from January to March, the southern summer. Cyclones rotate clockwise and turn south and southwest in the Southern Hemisphere, but rotate counterclockwise and turn north and northeast in the Northern Hemisphere, reflecting the different deflections of the Coriolis effect on either side of the equator.