What Are Fronts?

THE NARROW ZONE separating two different air masses is called a front and is often the site of rising atmospheric motion. Whenever different air masses meet along a front, the less dense, warmer one will be pushed up over the more dense, colder one. If the rising air cools to its dew-point temperature, cloud formation will begin, perhaps followed by precipitation. There are several types of fronts, depending on the manner in which one air mass is displacing the other and whether the front is moving.

What Processes Occur Along Cold and Warm Fronts?

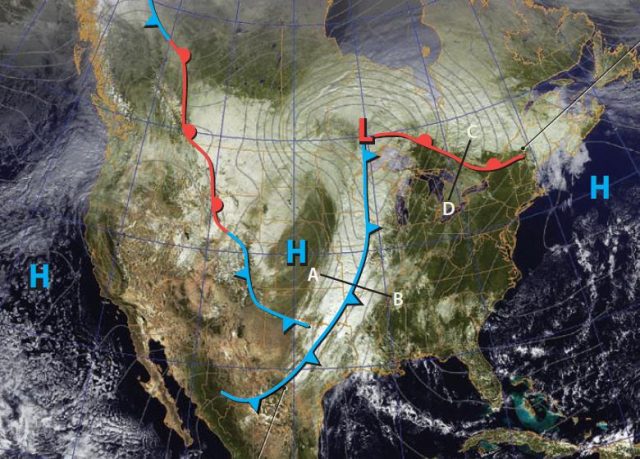

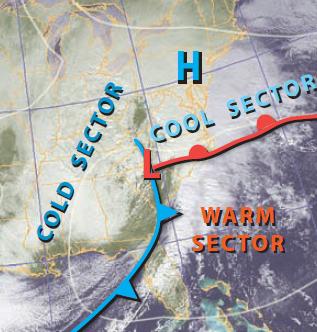

1. The map below shows several weather fronts as decorated lines, among the areas of high pressure (H) and low pressure (L). The thin gray lines are isobars (lines of equal pressure), and the background of the map is a satellite image showing cloud cover. Examine each of the features on this map and note any correspondence between the fronts, high and low pressure, and cloud cover.

2. The blue lines represent cold fronts, the leading edges of cold air masses. Blue triangles along a cold front indicate the direction that the cold air mass is pushing. The east-facing triangles on the long cold front in the center of the U.S. indicate that the cold front is pushing eastward. Cold fronts are usually associated with cP but can also occur along the leading edge of an A or mP air mass.

3. The red lines represent warm fronts, the leading edges of warm air masses. The red semicircles along a warm front indicate the direction in which the warm air mass is pushing. The warm front over northwestern North America is moving east. Warm fronts are usually associated with mT or cT air masses.

4. Let’s examine the weather in the eastern half of the U.S., beginning with the long cold front. As the front and associated mass of cold, dense air move east, it displaces and mechanically forces up the less dense warmer air that is east of the front.

5. Warmer air ahead of the cold front (such as at B) moves up and over the colder air, creating cumuliform cloud cover. The air west of the cold front (at “A” for example) is cold and dense, so it tends to sink, associated with increasing surface pressure (H). The pressure gradient is very steep, as reflected by closely spaced isobars near the cold front.

6. To the north is a north-moving warm front. Air south of the warm front (like at “D”) is warm and less dense, so it gets wedged over the more dense, cooler air north of it (at “C”). The gentle slope of this rising motion causes a shield of stratiform clouds over eastern Canada.

Cold Fronts

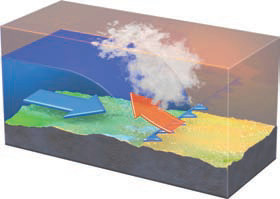

The figure below shows a cross section through a cold front along line A-B on the map above.

The cold air mass displaces the warm air mass. Cold air is more dense and forces the warm air upward. If the rising warm air cools to its dew-point temperature, cloud cover and perhaps precipitation occur along the front.

Warm Fronts

The figure below shows a cross section through a warm front along line C-D on the map above.

As the warm air mass follows and displaces the cool air mass, it slides up over the colder air. If the rising air cools to the dew-point temperature, stratiform clouds and perhaps precipitation occur along the warm front, but spread out over a significant width.

Comparing Warm and Cold Fronts

Compare the cold-front and warm-front figures, observing similarities and differences, then read the text below.

The slope at which a warmer air mass is pushed upward along a cold front is much steeper than the slope at which it is forced upward along a warm front. This tends to support cumuliform cloud formation along cold fronts, but stratiform cloud cover along warm fronts. As a result, precipitation along cold fronts tends to be intense, localized, and short-lived, whereas precipitation along warm fronts tends to be light, widespread, and long-lived. Use these tips the next time a weather front crosses your hometown.

What Is a Stationary Front?

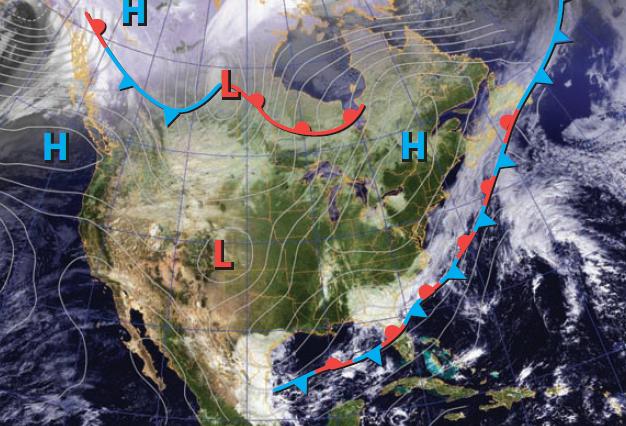

Sometimes, for a period of several hours or days, neither the cold air mass nor the warm air mass is displacing the other. There is a temporary stall in motion of the front, and so such a stalled front is a stationary front. On a weather map, a stationary front, such as occurs here along the Atlantic Coast of North America, is represented by alternating blue and red line segments with alternating blue triangles and red semicircles. The blue triangles point away from the cold air, and the red semicircles point away from the warm air, as shown in the cross section here.

On this stationary front, the blue triangles point east, so the cold air is trying to push east and must therefore be on the opposite side of the front (on the west side). The warm air is therefore on the east side. A band of clouds and precipitation is along the front, mostly on the cold air side (west of the front). Since a stationary front is not moving, prolonged precipitation can occur as the front sits over the same place for an extended time.

What Types of Weather Are Characteristic of Cold, Warm, and Stationary Fronts?

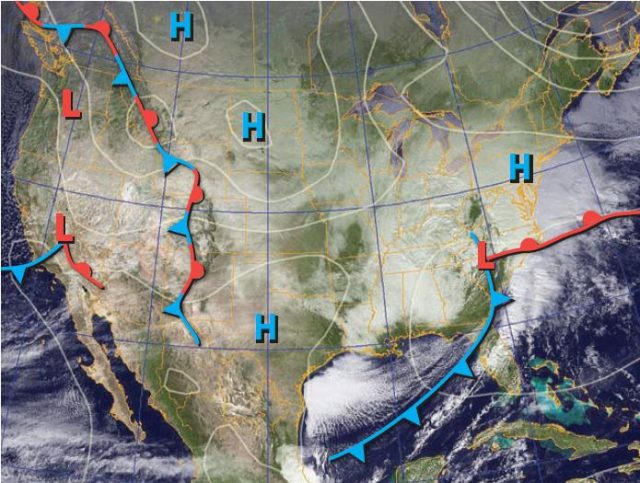

1. On this map, examine the weather fronts, locations of high and low pressure, and the underlying satellite image showing the distribution of clouds. Find a cold front, warm front, and stationary front and for each one sketch a simple cross section across the front, showing which way it is moving (or if it is not moving). After you have done this, read the rest of the text around the figure.

2. For the storm system in the southwest, the blue line marks a cold front that is moving to the south. The red line is a warm front moving to the northeast, but a warm front slopes opposite to the way it is moving (see the cross section on the previous page), to the southwest in this case.

3. The red and blue line along the mountains in the west-central part of the country is a stationary front. The cold air is trying to move to the west, so it must be on the opposite side (east). Based on the cross section above, the front slopes away from the cold air.

4. In the east is an east-west oriented red line that marks a warm front. The semicircles point north, so this is the way the front is moving.

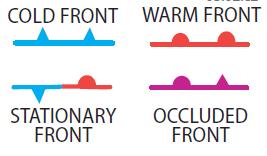

5. In the southeast, the blue line is a cold front. The cold air is on the northwest side, and the front is moving to the southeast. The warm front and cold front join at an area of low pressure, marked by the red L. Symbols for the four types of fronts are shown below. We discuss occluded fronts later.

6. This figure focuses on the low-pressure area in the east where the cold front (blue) meets the warm front (red). In this situation, the two fronts divide the region into three fairly distinct areas, called sectors. We reference each sector by the temperature of the air in that region relative to the two other sectors. The cold sector is behind the cold front and naturally has the coldest air.

7. The air in front of the cold front is the warmest and so is called the warm sector. The counterclockwise rotation around the low is bringing air north from lower latitudes and from oceans in the warm sector. The third region is intermediate in temperature and is referred to as the cool sector.

8. Clouds along the cold front are clumpy and probably cumuliform, but clouds in other areas are less clumpy and so are probably mostly stratiform.