What Influences Climates Near the Southern Isthmus of Central America?

THE SOUTHERN ISTHMUS OF CENTRAL AMERICA is geographically and climatically one of the most interesting places in the world. It is a narrow strip of land that connects Central America and South America and that separates very different waters of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. The climate of the region reflects intricately changing wind patterns and atmosphere-ocean interactions, including a migrating ITCZ, effects of the El Nino–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), and mountains with rain shadows on different sides at different times. The interactions between these various components lead to unusual climates and large variability within a single year and from year to year. The interactions have regional and global consequences.

1. The region around the Isthmus of Panama includes the southwardtapering tip of Central America, including Costa Rica and Panama, and the wider, northwest end of South America, including the country of Colombia. The spine of the isthmus is a volcanic mountain range in Costa Rica, but the Panama part is lower (hence the location of the Panama Canal). Colombia contains the north end of the Andes mountain range.

2. West of the land is the Pacific Ocean, and to the east is the Caribbean Sea, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. The Caribbean Sea is bounded on three sides by land — North America to the north, South America to the south, and Central America, including the Isthmus of Panama, to the west. On the east, the Caribbean is open to the main part of the Atlantic through gaps between individual, mostly small islands, of the Greater and Lesser Antilles. As a result of the Caribbean being partly enclosed and being within the tropics and subtropics, the waters of the Caribbean are generally warmer than those of the Pacific.

Regional Wind Patterns and Positions of the ITCZ

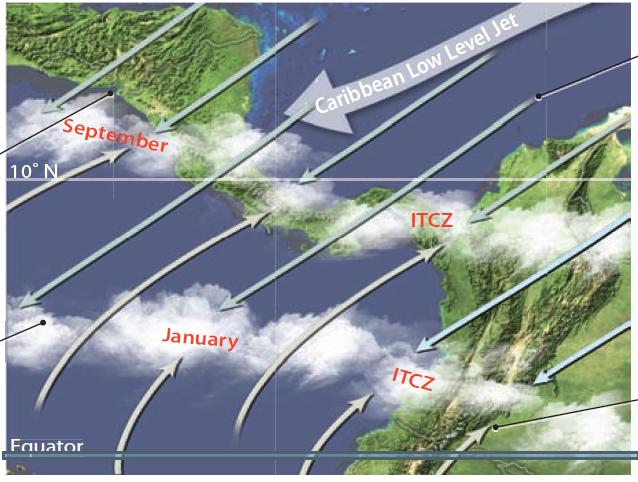

3. The isthmus and the adjacent parts of South America are north of the equator, but in tropical latitudes, centered around 10° N.

4. Crossing the region in an approximately east-west direction is the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), which has a seasonal shift north and south. In September it is as far north as 13° N.

5. In January, the ITCZ shifts to the south to near 5° N, following the seasonal migration of direct-overhead insolation to the south.

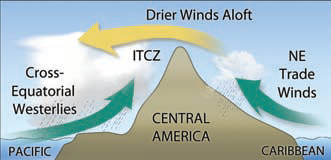

6. Much of the region is dominated by the northeast trade winds that blow from the Caribbean Sea, across the isthmus. Embedded in the trade winds is a low-altitude, fast-flowing current of air called the Caribbean Low-Level Jet (CLLJ).

7. In most tropical regions, the ITCZ is north of the equator during the northern summer (e.g., July) and south of the equator during the southern summer (e.g., January). In this region, however, the ITCZ stays in the Northern Hemisphere because of the cold Humboldt Current farther south. Related to this position are southwesterly winds that originated in the Southern Hemisphere as the southeast trades and are deflected back northeastward when they cross the equator as they flow toward the ITCZ. They reach farther north during times when the ITCZ is farther north.

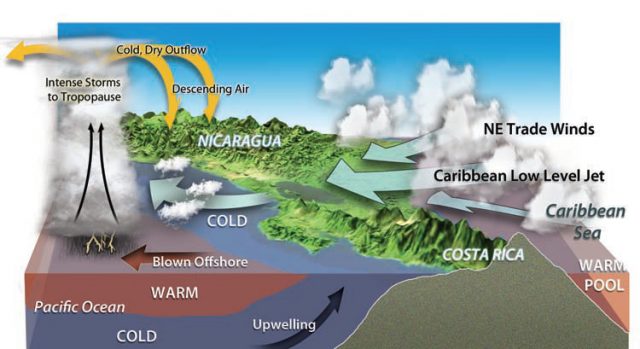

Wind Patterns and Weather During the Winter

8. From November to April, while the ITCZ is displaced to the south, the northeast trade winds and the CLLJ flow southwest across the isthmus, carrying warm, moist air from the Caribbean Sea. The Caribbean is part of the Western Atlantic Warm Pool, similar in origin and setting to the warm pool of the Pacific. The Atlantic warm pool forms when trade winds blow water westward until it piles up against Central America. When the moist air is forced up over the mountains of the isthmus at Costa Rica, heavy orographic rains fall on the Caribbean flanks of the mountains, while the Pacific coast experiences a dry season from the rain-shadow effect.

Wind Patterns and Weather During the Summer

9. During the opposite time of year, from May to October, the Pacific coast of Costa Rica experiences its rainy season. This corresponds to the northernmost migration of the ITCZ across the region, which allows the southwesterly winds to bring in equatorial Pacific moisture. As the moist Pacific air is forced eastward over the mountains, orographic rain falls on the west side. At the same time, the rising air in the ITCZ is over the area, producing heavy rain on a nearly daily basis.

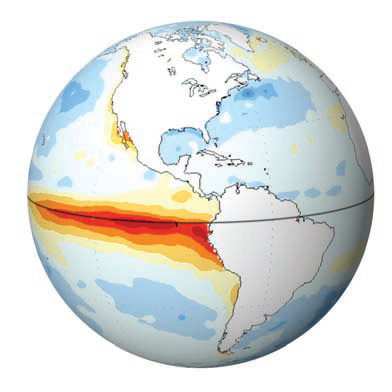

Regional Wind Patterns and Positions of the ITCZ

10. In July and August, the rainy season of western Costa Rica is temporarily interrupted by a dry spell of several weeks called the “Veranillos” (little summer). This dry spell occurs when the Caribbean Low-Level Jet (CLLJ) reaches its maximum intensity. The jet accelerates through the topographic break in the mountain belt between Costa Rica and Nicaragua.

11. Recall that the Caribbean Sea is part of the Western Atlantic Warm Pool, so it has very warm water during July and August (during the northern summer). As a result, the trade winds and CLLJ bring moist air across the region. As this air climbs the eastern side of the mountains, much of the moisture is lost to precipitation, yielding a rainy season on this eastern (Atlantic) side of the country during these months.

12. During July and August, the vigor of the trade winds and CLLJ blow surface waters of the Pacific Ocean offshore, causing upwelling of cooler water in the Gulf of Papagayo at the Costa Rica/Nicaragua border and a temporary suppression of the convective activity in the ITCZ. This causes the short dry season (Veranillos) on the western (Pacific) side of the country.

13. Warm, moist air farther offshore produces deep tropical convection, and an outflow of cooler, drier air descends over northwestern Costa Rica, preventing convection over the upwelling.

ENSO Warm Phase

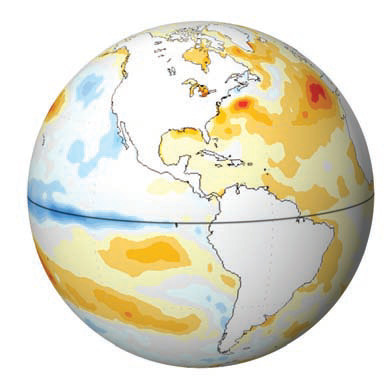

14. The weather patterns are already very interesting and unusual, but this region also falls under the influence of ENSO. These two globes show SST during ENSO warm and cold phases, relative to the long-term averages. Red and orange show SST above their typical value for a region, whereas blue shows SST that are colder than normal for that area. What patterns do you observe near Central America?

15. During a warm phase of ENSO (El Nino), warmer waters appear in the eastern equatorial Pacific, as shown by the red colors along the equator. Note that Pacific waters west of the isthmus are warmer than usual, but waters of the Caribbean are colder than normal. The warmer than usual waters of the equatorial Pacific are a site of rising air, drawing the ITCZ south and west of its usual position. The displaced ITCZ reduces rainfall along the Pacific flank of Costa Rica and enhances the Caribbean trade winds. This increases rains along the Caribbean slope, while the Pacific slope suffers from an enhanced rain-shadow effect and an extended Veranillos.

ENSO Cold Phase

16. The opposite occurs during a cold phase of ENSO, as shown in this globe. Waters are colder than normal in the equatorial Pacific west of South America, but are more typical offshore of Central America. The waters of the Caribbean, however, are warmer than typical. The changes in water temperatures and air pressures between the warm and cold phases of ENSO cause changes in the directions and strengths of winds. For instance, the CLLJ in June through August is stronger in warm phases than in cold phases. Changes in position of the ITCZ and strengths of winds cause differences in the risk of flooding, as depicted in the graphs below.