What Is a Tornado?

A TORNADO IS THE MOST INTENSE type of storm known, expressed as a column of whirling winds racing around a vortex at speeds up to hundreds of kilometers per hour. The May 1999 tornadoes in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, were estimated to have wind speeds over 500 km/hr. Fortunately, most tornadoes are less than several hundred meters wide, so they usually only damage narrow areas, but larger tornadoes can remain on the ground for hours and create a path of near-total destruction across one or more states.

What Is a Tornado and How Does One Form?

A tornado is a naturally occurring, rapidly spinning vortex of air and debris that extends from the base of a cumulonimbus cloud to the ground. Tornadoes typically have diameters of tens to hundreds of meters, but the largest ones can be 2 – 3 km wide. Most individual tornadoes remain on the ground for minutes to tens of minutes and have paths on the ground of less than a few kilometers. Some very rare, long-lived tornadoes track over 100 km, last a few hours, and destroy everything in their direct path.

This photograph shows the characteristics of a well-developed tornado, with the classic shape of a downwardtapering funnel. The tornado is visible because of the condensation of moisture, expressed as water drops, within the vortex. A brown cloud of debris picked up from the ground typically surrounds the base of the tornado, extending out farther than the vortex of strongest winds. As in the movies, if you are within the debris field, you are in trouble. Some tornadoes have wider and less elegant shapes, like a stubby, thick pillar.

Formation of a Tornado

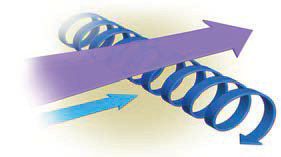

1. The formation of a tornado is complicated and not fully understood. Different sets of circumstances are present in different tornadoes, but tornado formation generally begins with horizontal winds moving across the surface. Wind speeds are usually higher aloft and decrease downward due to friction with the surface. This difference in wind speeds causes a vertical wind shear within the wind column. Wind shear can result in a rotating, subhorizontal vortex. Vertical wind shear generates a type of rotation known as mechanical turbulence, a normal occurrence, which by itself does not lead to severe weather.

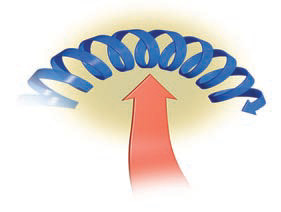

2. In an unstable atmosphere, rising air (an updraft) can perturb the rotating tube of turbulent air. With enough lifting, the tube will become more vertically oriented. As the tube is lifted, it generally splits into several short segments, some of which may even be rotating in opposite directions.

3. Eventually a segment of mechanical turbulence may become vertical, at which point it merges with the original and unstable updraft. Once it spans the distance from the cloud to the ground, it is a tornado. If a funnel-shaped cloud does not reach the ground, it is a funnel cloud. In the Northern Hemisphere, the parent storm system often rotates counterclockwise, so the tornado also spins counterclockwise, except in a few rare cases. As a tornado tightens its rotation, its wind speeds increase, making it a stronger, more powerful, and potentially more dangerous storm.

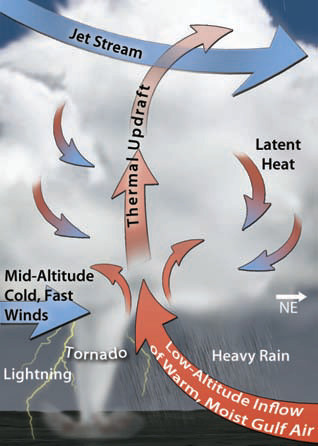

4. This figure shows the essential aspects needed to form a tornado. The main ingredient is a well-developed cumulonimbus storm cloud, especially one associated with a supercell thunderstorm. A favorable regional setting is another prerequisite, such as a mid-latitude cyclone that puts cold air adjacent to much warmer, moister air. The position and motion of the cyclone are in turn controlled by such factors as the position of the polar front jet stream.

5. Another necessary ingredient is vertical wind shear near the surface, caused by higher speed winds aloft and slower winds near the surface. Mountains and other topographic irregularities tend to disrupt a regular wind-shear pattern, which is one reason why tornadoes are more common in areas that have relatively low relief (little topography) than in areas with mountains.

6. Formation of a tornado — and its host thunderstorm — requires an unstable atmosphere. Without it, there will not be enough lifting to form the cloud and to realign a vortex into a vertical orientation.

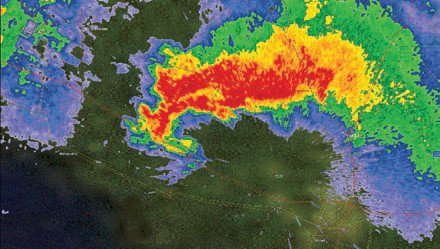

7. A storm must have strong updrafts in order to lift the horizontally spinning tube of air. The host storm must also possess strong internal rotation. Such rotation, which can be observed on weather radar, is one aspect weather forecasters use to gauge whether or not a severe thunderstorm is likely to spawn tornadoes. Storms that spawn tornadoes commonly have a hook echo pattern on radar.

What Weather Systems Produce Tornadoes?

Tornadoes are related to strong thunderstorms, which form in a number of settings. Most tornadoes occur in association with multi-cell or large supercell thunderstorms, which are generally associated with cold fronts. Others occur embedded in tropical cyclones or with more isolated single-cell thunderstorms.

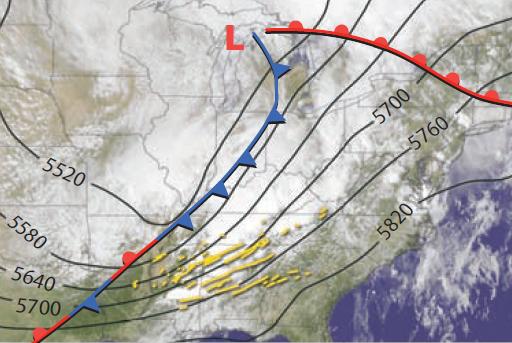

Associated with Cold Fronts

Most catastrophic tornadoes are associated with multi-cell or supercell thunderstorms of the Great Plains and Southeast, usually in the warm sector of cold fronts. On the map above, a cold front (in blue) stretches south from a cyclone (marked by an “L”) over the Great Lakes. In front of the cold front are yellow lines showing the tracks of tornadoes. These tornadoes formed in association with squall-line thunderstorms along the dry line. Such tornadoes would more likely occur in the afternoon and early evening when thunderstorms are most active.

Tropical Cyclones

Tropical cyclones, like hurricanes, spawn tornadoes too, but a large percentage of these are not terribly strong because the upper-air pattern favored for tornado development is obliterated by tropical cyclone circulation. In the Northern Hemisphere, tornadoes are most common in the northeastern quadrant of a storm, such as embedded in the thicker swirls of clouds in the northeastern (upper right) part of Hurricane Isaac. Tornadoes closer to the center of the tropical cyclone may occur at any time of day and are generally weaker than those farther from the center, which mostly occur in the afternoon.

Single-Cell Thunderstorms

Single-cell thunderstorms can spawn tornadoes, but the tornadoes are generally small and weak, in part because the storm system is itself typically not very large or powerful. Tornadoes formed in this setting are generally restricted to the afternoon, when surface heating destabilizes the atmosphere and causes a peak in thunderstorm activity. Tornadoes formed in any setting can have a distinctive, sharp, low-forming cloud, called a wall cloud, indicating that a tornado may be near. Storm chasers (people who purposely try to get close to a storm to observe and photograph it), are on the lookout for wall clouds.

How Are Tornadoes Classified and What Type of Damage Do They Cause?

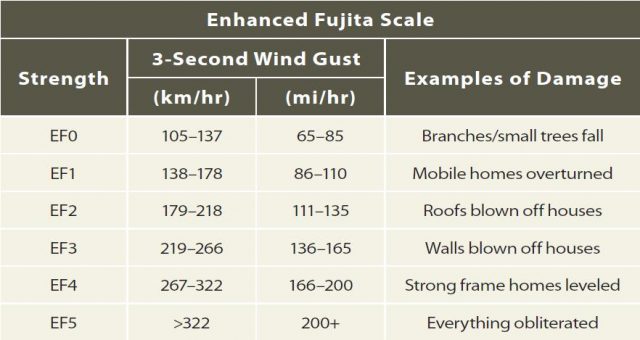

Tornadoes are classified using the Enhanced Fujita (EF) scale (shown in the table below), which is based on estimated wind speed as evidenced by damage. The amount of damage a tornado does is controlled by its strength (i.e., its EF rating), how long it stays on the ground, and what type of features are in the way (e.g., a city versus farmland).

This tornado is an aweinspiring sight, but such thinly tapered tornadoes are typically not the strongest. The blue sky in the background suggests this may be related to a single-cell thunderstorm. It is passing over agricultural fields, so it may cause relatively limited damage.

This photograph illustrates the type of near-total destruction that tornadoes can cause. The wood-frame houses in the foreground were completely disassembled by the strong winds within a tornado, while the houses in the background are still standing (kind of ) but suffered major damage.