Where and When Is Fog Most Likely?

CERTAIN SETTINGS AND CONDITIONS are conducive to the formation of fog, so we might anticipate that some regions will have more fog than others. Also, as temperatures and humidity change with the seasons, some times of the year are likely to be foggier than other times. Considering all the places you know, which ones have more fog, and why do you think this is so?

In Which Settings Is Fog Likely?

Formation of fog occurs when the combination of moisture and temperature causes the air to reach saturation (100% relative humidity). What settings would most likely have fog?

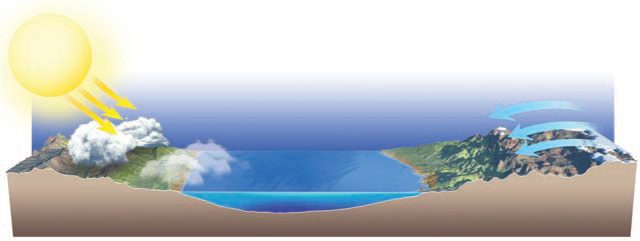

1. Examine this diagram and try to identify any factors that you think could influence the amount of fog. Then read the different blocks of text, which will describe some of these factors — you may identify more than are described.

2. An important factor is the climate of a place, especially the temperatures and humidity levels that are typical. Regions at lower latitudes will generally receive more direct insolation than regions at higher latitudes, and this variation greatly affects the temperature, which in turn controls how much moisture the air can evaporate.

3. Another important control on the frequency of fog will be the typical humidity of a place. Is it a humid place, commonly covered with clouds, or a drier, inland desert that commonly has clear skies?

4. Proximity to the ocean or other large bodies of water will clearly be a major factor in fog formation, since such water bodies can contribute abundant moisture to the air, if they are warm enough. Water also warms up and cools down more slowly than land, so it tends to help moderate any temperature swings of the adjacent land (cooler days and warmer nights than land farther away from water).

5. Prevailing wind directions are important since they can bring moist or dry air into an area. Especially important is whether breezes along a shoreline blow onshore or offshore (toward the water).

6. Topography and elevation are clearly key factors, since they control temperatures and influence local wind directions. Mountain slopes have upslope winds at some times and downslope winds at others. They also interact with the prevailing winds.

What Regional Settings Are Favorable for the Formation of Fog?

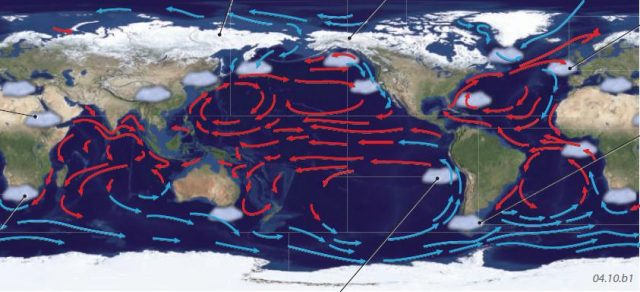

This map shows major ocean currents and land cover. Warm ocean currents are in red and cold ocean currents are blue. On the land, green colors show abundant vegetation, tan colors show areas with less vegetation, and white areas are covered by ice and snow. Examine this map and think about how these ocean currents and regional patterns could influence the frequency of fog.

Radiation fogs are common in inland areas, which often experience clear skies and a significant drop in temperature at night. Radiation fog can persist when there is a temperature inversion to stabilize the atmosphere and hold the fog in place, low to the ground.

Latitude plays a major role in whether fog forms because it influences regional temperatures, humidity, wind directions, ocean currents, and the types of storm systems.

Ice and snow on the land and on frozen oceans greatly cools the adjacent air, causing intense temperature inversions over the polar ice caps. These inversions lead to widespread radiation fog, especially beneath the polar highs.

Fog is frequent along the windward sides of mountain ranges, such as those along the western side of North and South America. Near these mountains, fog is more common where moisture is abundant, and this is controlled by regional patterns in winds and ocean currents.

Great Britain is very well known for its cold and damp advection fogs.

Over the open oceans, evaporation fogs are common as water evaporates and rises into overlying cooler air.

Ocean currents greatly influence fog development. Advection fogs are common where cold ocean currents extend into otherwise warm areas near the coast, such as along the western coasts of South America and southern Africa. Sometimes these fogs provide the major source of moisture in desert areas, such as the Atacama Desert of Chile and the Namib Desert of Namibia.

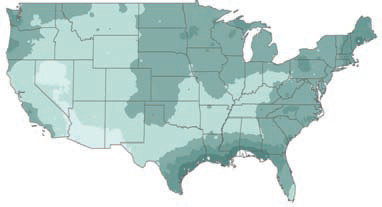

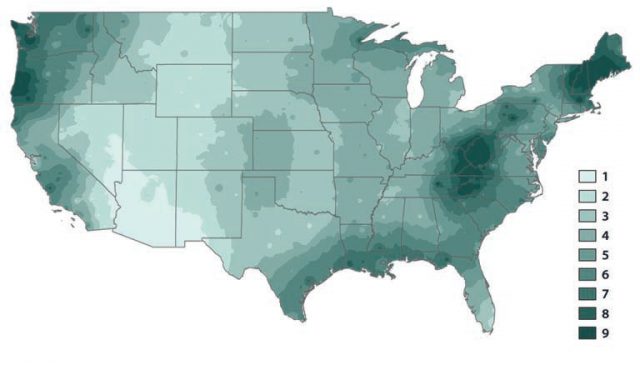

Which Parts of the U.S. Have the Most and Least Fog Days?

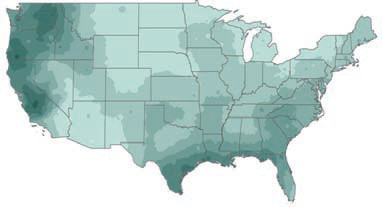

Mean Number of Fog Days Per Month (average for entire year)

This map shows the average number of days of fog experienced by areas in the conterminous 48 states, with darker colors indicating more fog. Observe the patterns on this map, noting how common fog is in the area where you live or visit.

The Pacific Northwest frequently has fog. As saturated marine air is pushed by the mid-latitude westerlies toward the Pacific Northwest, it gets chilled from beneath by a cold ocean current, causing an advection fog. Other fog is caused by air moving upslope on the western sides of the Cascades and other mountains. San Francisco experiences advection fog for the same reason, and the mountains surrounding the bay cause the fog to be funneled and focused in the Bay Area.

The continental interior often experiences clear nights, which may cool the air to the dew-point temperature and create radiation fog. Fog is less common in the Desert Southwest, which often lacks abundant moisture.

The Gulf Coast experiences advection fog as warm, moist air from the Gulf of Mexico is advected onshore due to clockwise circulation around the Bermuda-Azores high-pressure area.

The Great Lakes and other large bodies of water support evaporation fog, particularly in fall.

In New England and parts of the Appalachian Mountains, fog often occurs as cyclones and anticyclones over the Atlantic push moist and relatively warm maritime air over the colder continent. This creates advection and precipitation fog. Cyclones and anticyclones also produce upslope fog farther south, along the flanks of the Appalachian Mountains. Valley fogs are also common in this region.

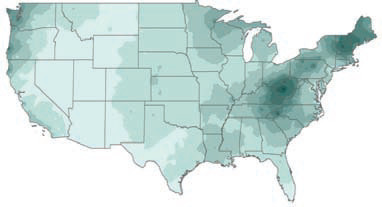

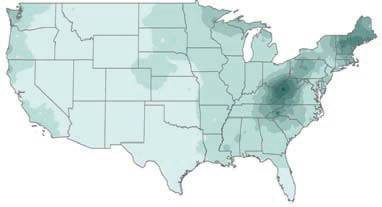

Seasonal Variations in the Number of Fog Days Per Month

Winter

In January, advection fogs occur frequently in the Pacific Northwest and other coastal areas. These are caused by relatively warm air over the oceans moving over much colder land, which cools the air and leads to the formation of fog.

Fall

Fall, like summer, is a time of less frequent fog, except perhaps for upslope fogs in the Appalachians. In addition, downslope winds at night can trap moisture in the adjacent valleys. In subsequent months, the patterns characteristic of winter begin to become reestablished.

Summer

Fog is least common in most of the U.S. in summer. Even though the vapor pressure is high, higher temperatures mean that it is difficult for the air to reach saturation. Fog is most common in New England and in mountainous areas, such as West Virginia, where fogs are largely attributable to upslope, precipitation, and radiation fogs.

Spring

By March, fogs become less frequent across many parts of the country. Still, radiation fogs tend to be fairly common across the middle of the country under clear nighttime skies. The Gulf Coast experiences frequent fog caused by moist air from the Gulf of Mexico.